In 1990, Chile was at a historic crossroads. Following a landmark 1988 referendum where the people voted to remove the bloody and oppressive regime of Augusto Pinochet, a gradual return to democracy began to loosen the shackles military officials had placed on arts and culture for over a decade. As if waiting to exhale, these slowly regained freedoms fueled a thirst for new voices and perspectives, which is why when emblematic San Miguel band Los Prisioneros released their fourth LP, Corazones, on May 20th 1990, the album that would become their greatest pop legacy was not an immediate hit.

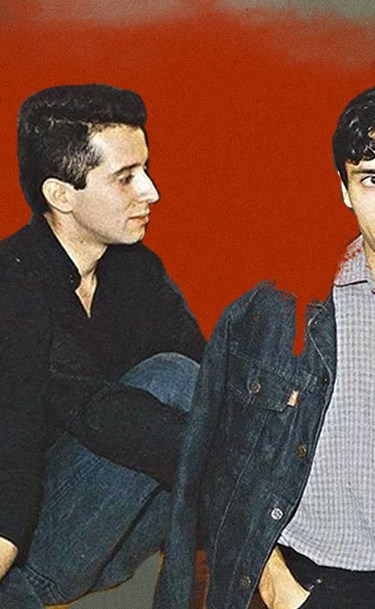

Los Prisioneros were founded in 1979 by three high school friends: Jorge González (15), Miguel Tapia (14) and Claudio Narea (13). First named Los Vinchukas and later rebranded as Los Prisioneros, the teenage trio started out writing parody songs inspired by The Beatles and Kiss, frequently playing school shows before eventually seeking to formalize their musical identity a few years later. In December 1984, the band released their first album, La Voz De Los 80s—a scrappy, lo-fi rock ‘n’ roll record with a sharp dissident edge, which proved controversial at a time of extreme censorship from the dictatorship.

With each fiery new song and album, the buzz (and censorship) around Los Prisioneros snowballed. The band signed to EMI Chile in 1985, with subsequent albums Pateando Piedras and La Cultura de la Basura propelled by cutting socio-political songwriting and a sound that emulated European new wave. Iconic early anthems like “Quieren Dinero,” “El Baile De Los Que Sobran” and “De La Cultura De La Basura” established Los Prisioneros as tenacious working class narrators with an artsy twist, experimenting with samplers, synthesizers and drum machines that thrust a spirit of resistance onto the dance floor. Still, the label demanded rock music, and while songs like “Maldito Sudaca” and “We Are Sudamerican Rockers” proved to be blockbusters, guitar-driven songs became increasingly relegated to the sidelines. In fact, Jorge González was often vocal about how tiresome he found rock n’ roll, infatuated instead with dance music like disco for its joyful lack of pretense and egotistical leaders.

In July 1989, Los Prisioneros began working on the demos for what would become Corazones, which González took to Los Angeles, California, in October of that year. González flew out only with band manager Carlos Fonseca, as Tapia was unable to secure a visa to enter the U.S., and Narea had grown distant after seeing his role as guitarist and occasional songwriter increasingly diminished. In L.A., González entered the studio with then-rising Argentine producer Gustavo Santaolalla, who made a name for himself with his band Arco Iris and by collaborating on popular albums for Wet Picnic and León Gieco. Santaolalla brought an astounding new level of polish to Los Prisioneros, where all previous records had been produced by González, infusing jagged electronic melodies with soaring pop production and regional instruments like charango in order to solidify a sonic identity that was original and unquestionably Latin American.

“It was the first record where I received a producer credit,” Santaolalla told Chile’s Teatro Nescafe de las Artes Magazine in 2018. “It’s a key record for me, in part because it was my first opportunity to get to know and work with Jorge [González], and because it was massive. I think it captured a very special creative moment for Jorge, a very difficult personal moment, and a time of change and conflict within the band.” Corazones would become the first in a series of genre defining smashes overseen by Santaolalla, which later included Maldita Vecindad’s Circo (1991), Café Tacuba’s Re (1994), Julieta Venegas ‘Aquí (1997) and Molotov’s Donde Jugarán Las Niñas? (1997).

The songwriting on Corazones also marked a momentous thematic shift for Los Prisioneros, still eviscerating classism and social conservatism on anthemic cuts “Tren Al Sur” and “Noche en la Ciudad,” but also expanding into romantic intimacy, wholly new territory for González. Visceral songs like “Amiga Mía,” “Con Suavidad” and “Estrechez de Corazón” speak of secret lust and a romance gone painfully sour. It would later come out González had been in a tumultuous affair with Narea’s wife, Claudia Carvajal, who inspired the rollercoaster of emotions behind his songs and led to the guitarist’s official departure from Los Prisioneros months before the album’s release. Corazones became the band’s final title, and due to the immense tension and creative protagonism González enjoyed in development, many people credit the album as his unofficial solo debut.

“Now the album doesn’t sound like any group from the USA or England, and that’s a good thing,” González told Rock & Pop Magazine in 1990. “Here in South America that sounds like a disadvantage, but no, Latin American romantic music is much more attractive than a band imitating U2 or Depeche Mode.”

At first, fans and critics were so taken aback by the change in tone, that lead single “Tren al Sur” struggled to find its footing on Chilean radio for months. It wasn’t until the video was picked up by MTV that it skyrocketed on the charts, catapulting album sales and going triple platinum by the end of the year. As more singles hit the airwaves, fans became fixated with González’s songwriting, which evolved from evoking Nueva Canción legends like Victor Jara and Violeta Parra to encompass influences from Spanish hitmakers like Camilo Sesto, El Duo Dinámico and Mecano.

Corazones is also the best showcase of González’s ambitious hybridity and theatrical wit. Devastating album closer “Es Demasiado Triste” could be right out of a musical tragedy, while the visionary “Corazones Rojos,” which was originally written in 1986 with all-women’s performance art group Cleopatras, features a call and response structure, record scratching and bold raps about machismo and women’s oppression. Remarkably ahead of its time, the song is like a dizzying collision of Blondie’s “Rapture,” Pimpinela’s “Olvidame y Pega La Vuelta” and Lastesis’ “Un Violador En Tu Camino.”

Chile has changed radically over the past 30 years, but both Corazones and Los Prisioneros are as relevant as ever. “Tren al Sur” and “El Baile De Los Que Sobran” are frequently heard booming from the massive crowds that have been occupying major avenues and public squares since October last year. These protests against socio-economic inequality and poor public services are a direct result of the neoliberal policies that came into effect in the 90s following the return to democracy, with all three members of Los Prisioneros coming out vocally in support of the proposed constitutional reform.

In 2015, González suffered a near-fatal stroke. Though he has largely recovered, he announced his retirement from stage and music in 2018, performing a final show at the Cumbre del Rock Festival later that year. On the other hand, Tapia and Narea have been touring under the moniker of Los Prisioneros for the past decade, and while many fans cling to hope of a future reunion, all musicians have shot down such speculation. Ultimately, the undeniable legacy of Los Prisioneros can be traced from the 1980s all through the wave of indie artists that emerged in the 2010s, with everyone from Javiera Mena to Alex Anwandter, Dënver and Gepe acknowledging the lasting influence of their electronic experiments and unflinching emotional songwriting.

All hail Corazones, Chile’s first synthpop masterpiece!