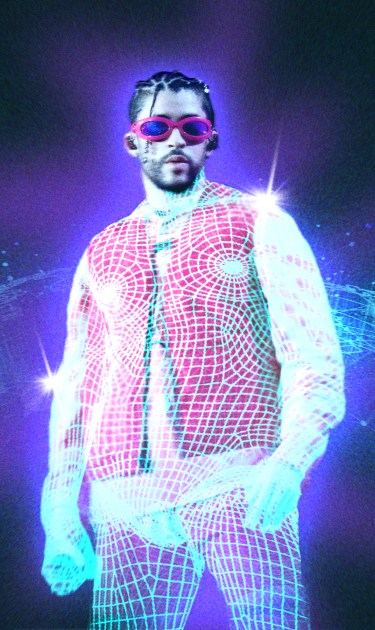

Venting his frustrations earlier this month, Bad Bunny took to his WhatsApp channel to share his heated feelings about an AI-generated song going viral on TikTok that used his voice without his consent. He wrote to the channel: “If you guys like that shitty song that is viral on tiktok, get out of this group right now. You don’t deserve to be my friends and that’s why I made the new album, to get rid of people like that. So chu chu chu out.”

However, fan response has been somewhat divided. On one hand, there are those who argue that Bad Bunny might have overreacted, insisting the song was solid and there was nothing else to it. Others are questioning the trajectory of music and its authenticity in the age of AI. But the reality is that this situation extends beyond Bad Bunny and the specific track in question.

Concerns about AI-generated art have existed since the technology first became open to the public. From questions on originality and creativity to concerns about copyright, policing AI-generated content is simply a big question mark. In light of that, the only thing left for us, the consumers, is to figure out the ethics of it all. What are we comfortable with? What do we seek in our media, empty quantity or authentic quality? And where does consent fit into it?

In addressing these concerns, Claire Leibowicz, Head of the AI and Media Integrity Program at The Partnership on AI (PAI) and a doctoral candidate at Oxford, emphasizes to Remezcla, “Consent is the best practice in this moment where we don’t know how the law is totally going to pan out.”

As fans, do we care if Bad Bunny consented to his voice being used in a song or not? And most importantly, should we, especially if the AI-generated song is “good”? While everyone is entitled to their own opinions on the matter, we should care. Truthfully, the answer will depend on why each person listens to music and what they value most — the person behind the piece or the finished product itself. In a world where AI technology is only becoming more and more accessible, this thought process — along with a good media literacy course — should be at the top of our minds as we figure out the ethical way to consume this type of content.

While concerns about the use of AI deep-fakes to trick people during election time or to use female streamers’ faces on porn sites without their consent should be at the top of the list, that doesn’t mean the stealing of recording artists’ voices and work shouldn’t also be discussed. “I’ve heard colleagues who said within five minutes of poking around on the internet they were able to deep-fake Joe Biden’s voice,” Leibowicz says. “It’s captured the public imagination. More people are using these systems, and people are understanding the extent to which they’re embedded in our humanity in the current moment.”

In September, Harvey Mason Jr., CEO of the Recording Academy, announced that while the Grammy Awards won’t be “awarding AI creativity,” it won’t automatically disqualify the people who use it either. To be more specific, a song can be nominated for a writing category if an AI is performing a human-written song, and it can be nominated for a performance category if a human is singing an AI-written song. Still, this gets murkier when you consider what Mason Jr. said about a song still needing general distribution and to be commercially available — which AI-generated songs are not, or at least not as of right now.

As fans, do we care if Bad Bunny consented to his voice being used in a song or not? And most importantly, should we, especially if the AI-generated song is “good”?

Stealing others’ original works still happens even without the use of AI. Trap and reggaeton are genres built on sampling — especially when artists are only starting out. The difference is that record labels (and their artists) have processes regarding asking permission, distributing percentages on royalties, and ownership. And when that system fails, there is legal precedent for what to do exactly. For example, there’s the instance when Missy Elliot sued Bad Bunny’s label for using the beat from her song “Get Ur Freak On” without proper permission on “Safaera.” Sure, there is an argument for now-famous reggaetoneros using samples without permission during their early years. But the reality is that those songs didn’t go as viral as the AI-generated songs do now — and even then, artists were not fans of sites like SoundCloud or LimeWire either.

“One of the best practices that’s in the White House regulation and a lot of the policies has to do with watermarking or labeling content as AI-generated,” Leibowicz shares. “Would Bad Bunny have felt better if at the beginning of the track or every 30 seconds, it said something like, ‘This is not really Bad Bunny’? I actually don’t think that necessarily would have made him feel better.”

People argue that Benito will be just fine and that he’s not losing anything — especially since FlowGPT, the creator of the viral song, deleted all his TikToks. Still, fans of the song are reuploading it on the platform. On Nov. 10, a TikTok showing the same AI song being played at a crowded club in Mexico garnered over 1.9 million plays and 225,000 likes in a single week. To them, it’s simply a good song. It’s clear that a middle ground between innovation and regulation is desperately needed. As society grapples with the ever-expanding applications of AI, the intricacies of governing this rapidly evolving technology prove to be nothing but a complex challenge.

“There’s so many different uses for the technology, and that is why governing it is actually quite hard in certain instances. It takes a long time for regulation to be precise to all these examples,” Leibowicz says. “I think it’s this gradient of stripping someone of their autonomy and agency.”

AI is not inherently evil, nor is all the content created with it stolen. AI is a tool and should be used as such by artists — just like the use of auto-tune. Instead of using AI to trick people, it’s just another producing tool artists use now. Reframing it to fuel our creativity and create original work is the way forward.

As of right now, there is no correct answer, and this piece is simply the beginning of a larger dilemma. While we, as individuals, have little control over the actual development of the technology itself, what we can do is delve deeper, self-reflect on ourselves as music consumers, and start conversations about our responsibilities as such.