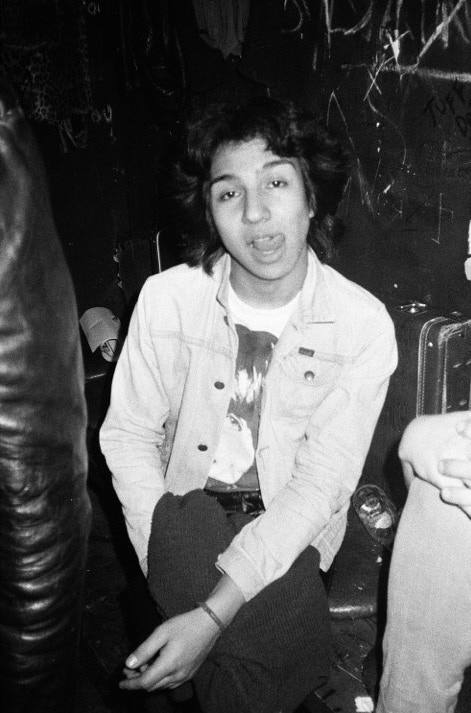

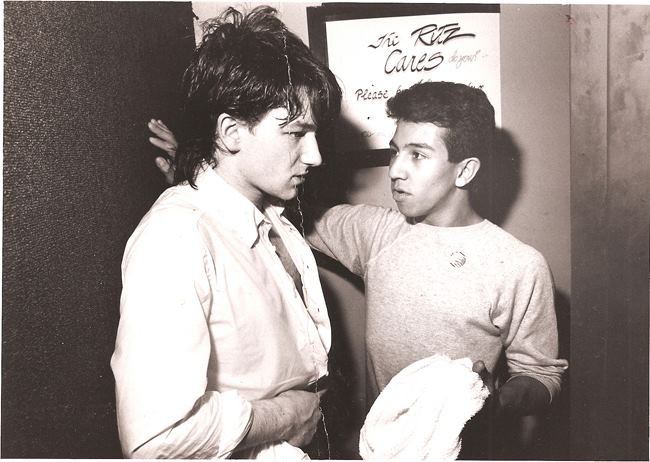

His name and face may only be familiar to music industry insiders, but without Michael Alago, today’s metal landscape would probably look a lot different without the invaluable foresight and undeniable love for the genre he has shown since the 1980s.

In the documentary Who the F**k is That Guy? The Fabulous Journey of Michael Alago, filmmaker Drew Stone looks at the impact Alago has had on the rock industry and re-examines how a gay Puerto Rican teenager from Brooklyn became the music executive who signed Metallica to its first recording contract, among other notable achievements.

In an interview with Remezcla, Alago talked about what he saw in Metallica that drove him to sign them over 30 years ago, how the industry has changed during that time, and why success is less about talent and more about timing.

Who the F**k is That Guy? The Fabulous Journey of Michael Alago is available on VOD and iTunes starting July 25.

On his initial reaction to the idea of a documentary on his life and career

It took me back and I thought for a moment, “Wait, a film about me?” I had a lot of questions, of course, because I didn’t know [director] Drew [Stone] well. We had a couple of meetings and a few lunches. Then, I think my ego took over and I said yes. After that, I was totally open to the process.

On revisiting the more personal parts of his past

Drinking and drugging and addiction are never pretty, but I think it was important that everyone got a complete picture of me. I wanted to be an open book and let everybody know what was going on. Sometimes if you don’t pay attention, the music business coupled with willfulness can destroy you. The beauty of it all is that after a while, I paid more attention, I got sober and my new life is awesome.

On what he was looking for as a music executive in the 80s

Whether it was a singer or songwriter or group of musicians, what I always looked for was somebody who had a unique point of view. You hope when you see them live, they have a certain charm and charisma about them so that the crowd feels that and there is an energy that goes back and forth. That’s what happened when I saw Metallica in 1984. I saw them live. They were all wildly charismatic on stage. I thought [vocalist/guitarist] James [Hetfield] was a natural-born ringleader. I thought, “These people are going to be in my life.” I really did think they were going to be the biggest band in the entire world.

On how “discovering” a band has changed over the years

From 1980 to 2004, I really was out every night. I collected all my favorite music papers from all the cities I loved that I knew had thriving music scenes, and if someone sounded fabulous or looked fabulous, I went to see them. These days, I think because of corporations’ bottom lines, people are afraid to be adventurous and sign stuff. I hear about [music executives] going to YouTube to see how many views somebody has. For me, that says nothing. That band could’ve sat on YouTube all night with their friends and kept hitting like, like, like. It’s a one-dimensional thing you see on a screen. You don’t really know if the person is the real thing or not. As much as technology has helped us, I think too many people are looking at numbers. I think that’s a bit cold.

On the stars not always aligning for bands he signed

I think when one signs an artist or group, you always hope for the best. You hope you make the best record you can make. You hope that marketing and promotions and publicity and radio are all in sync with you. But when it just doesn’t happen, and the moon is not full and all these things don’t come together, it becomes a very big disappointment to myself and the artist and the label. That’s just the way of the world. Not everything is going to be a wild success, but you do the best that you can with the artist.

On which band he wishes would have gotten a second chance

There was a band I signed when I was with Elektra [Records] called Drown. We made the record. It was really cool and nothing happened. When I went to Geffen [Records], I really believed in the band, so I signed them for a second time, and nothing really happened. It’s about timing and sometimes things just don’t happen. Sometimes there’s no explaining it. Even when you hear it, you’re like, “Wow, that’s good music.” But, you know, not everyone makes it to that big stage.