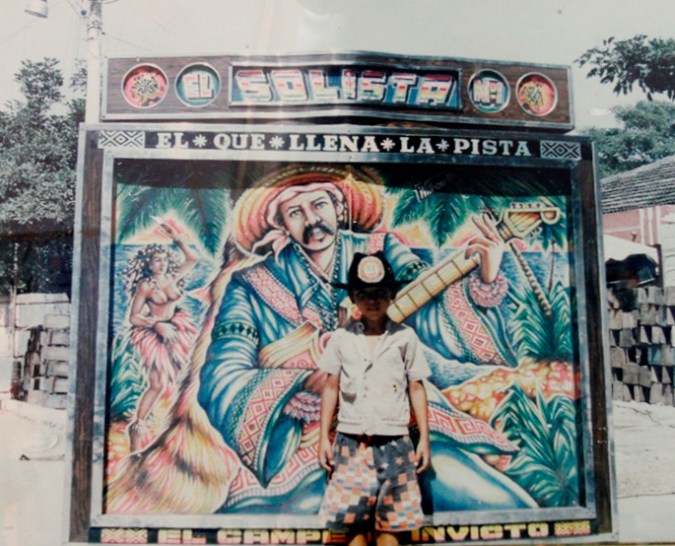

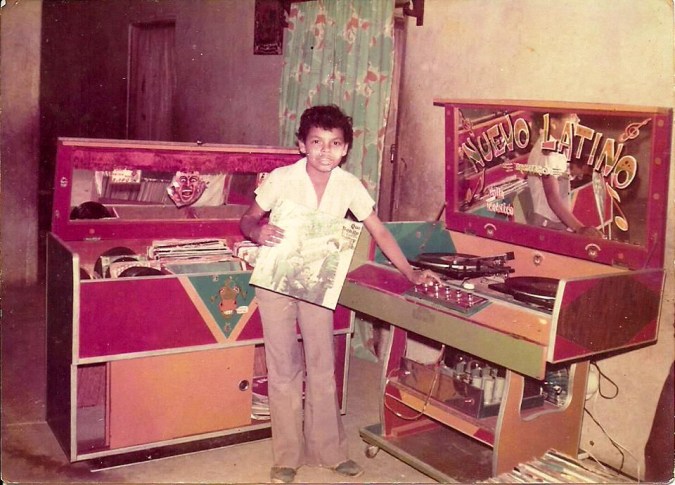

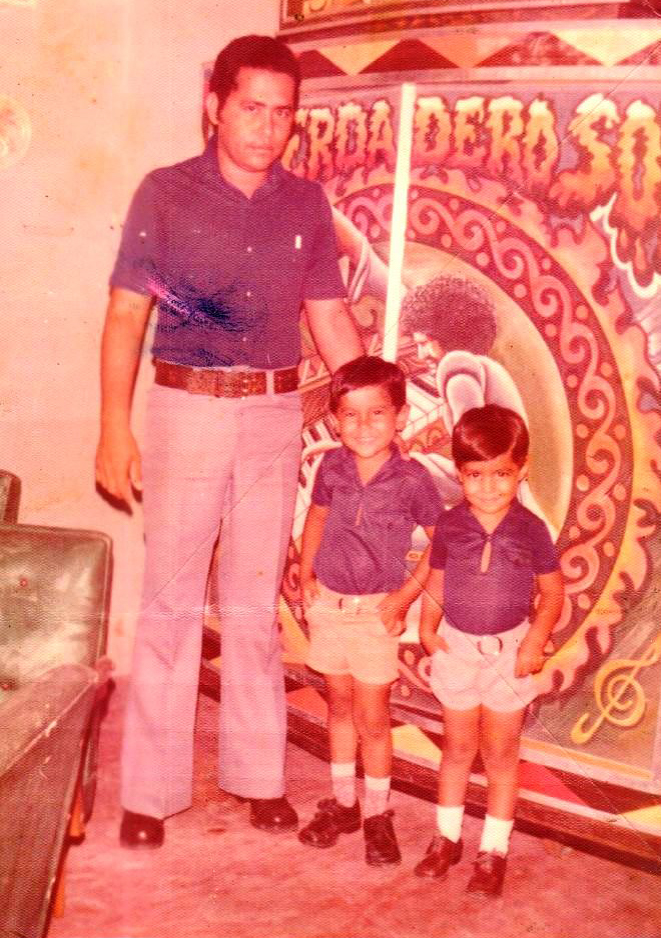

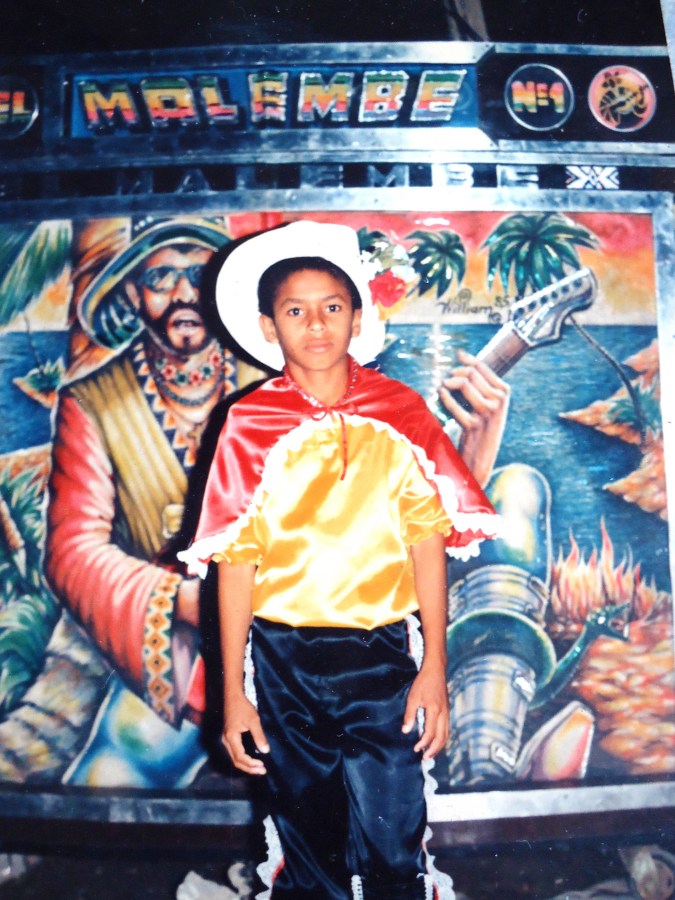

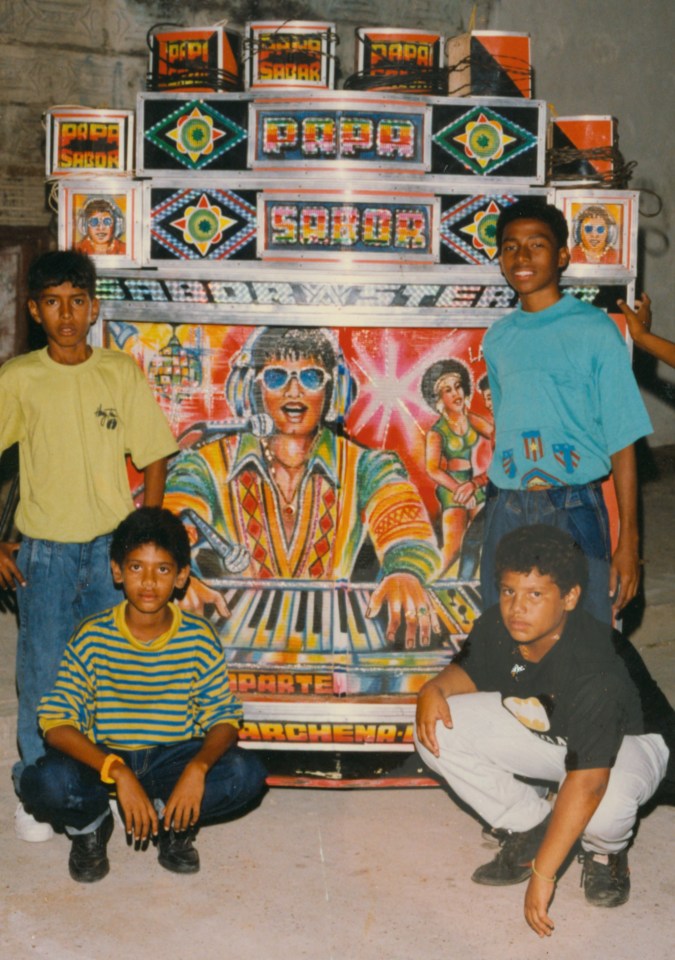

At age seven, Fabian Altahona Romero must have been about half the size of a picó — just a small boy, practically trembling as the music roaring from the massive, six-foot Colombian sound systems threatened to knock him off of his feet. Each year, he’d count down to Carnaval parties and bailes de verbenain his native Barranquilla, because these events meant that local DJs would heave in their handcrafted picó boxes, decorated in iridescent paint and neon illustrations, and bring the community together in a blare of thundering Afro-Colombian sounds.

Urban legends insisted that picós were so loud and powerful, they could explode plastic water jugs and give listeners a toothache, but those stories never deterred Altahona. He’d stand as close as he could to the picós and watch them with wide eyes, convinced they were objects conjured out of the superhero comic books he’d read with his brothers.

Many novelties that fascinate children lose their charm eventually, but picós continue to wield power over Altahona almost 20 years later. Since 2005, he’s been documenting the history and culture of the Colombian sound systems on his blog AfriColombia, which honors Afro-Colombian heritage. By unearthing photos and stories of picós and their owners, known as picoteros, Altahona has brought a swell of global attention to the music tradition.

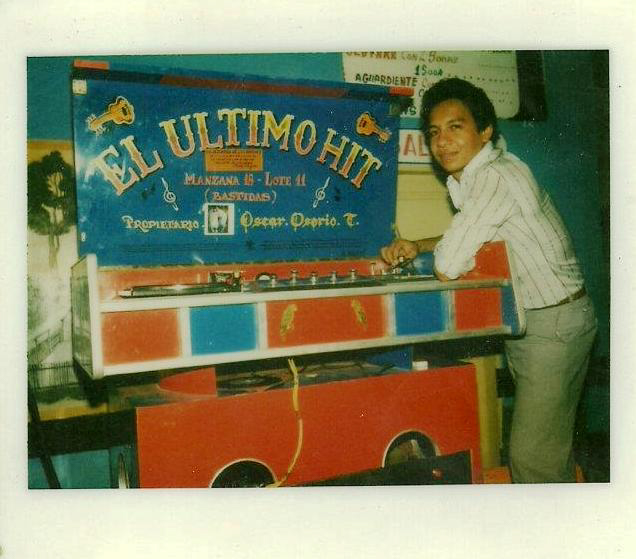

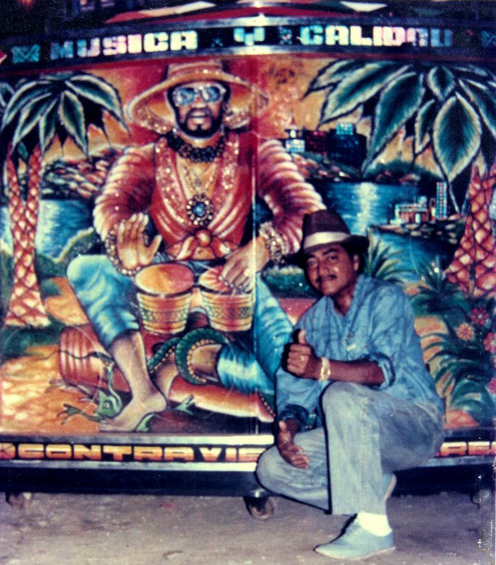

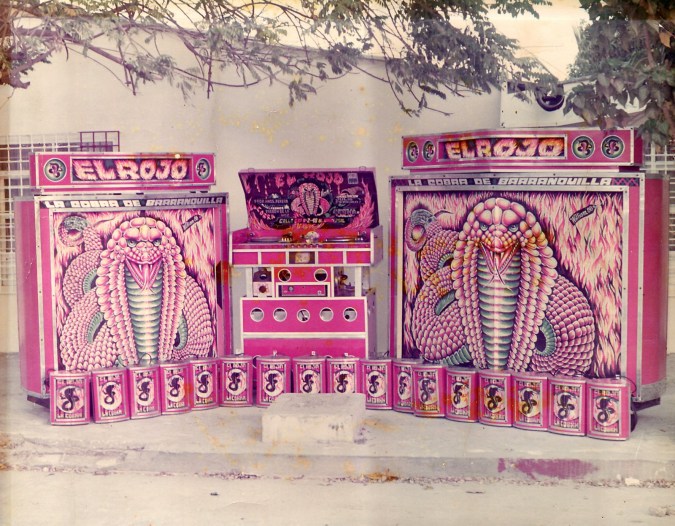

“I just loved everything about picó culture — the environment, getting to know the community, bringing the barrio together. And what always drew my attention were the paintings — those paintings that decorate the picós and give each one its life. I’d see them and I’d think I was looking at Superman or something like that,” Altahona said. “It’s something that is made completely by hand — and it’s ours.”

Picós served as communal entertainment for Colombians in coastal areas, where a majority of the country’s black population lives. The culture of the sound systems have always embraced and promoted African music and, as FACT Mag points out, “played a vital role in building a collective diasporan identity for many Afro-Colombians living in a country heavily scored along race and class lines.” Picós not only represent Afro-Colombian culture through music, but also tie together art, dance, and community.

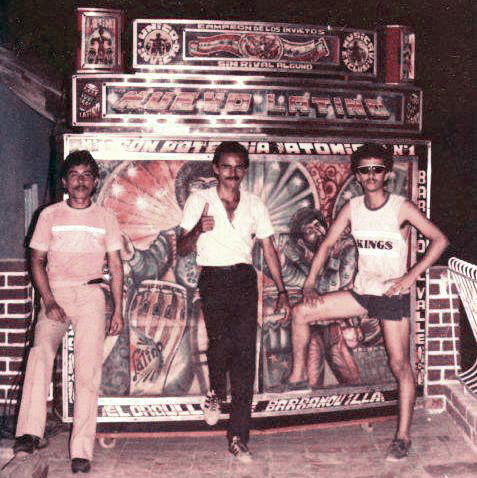

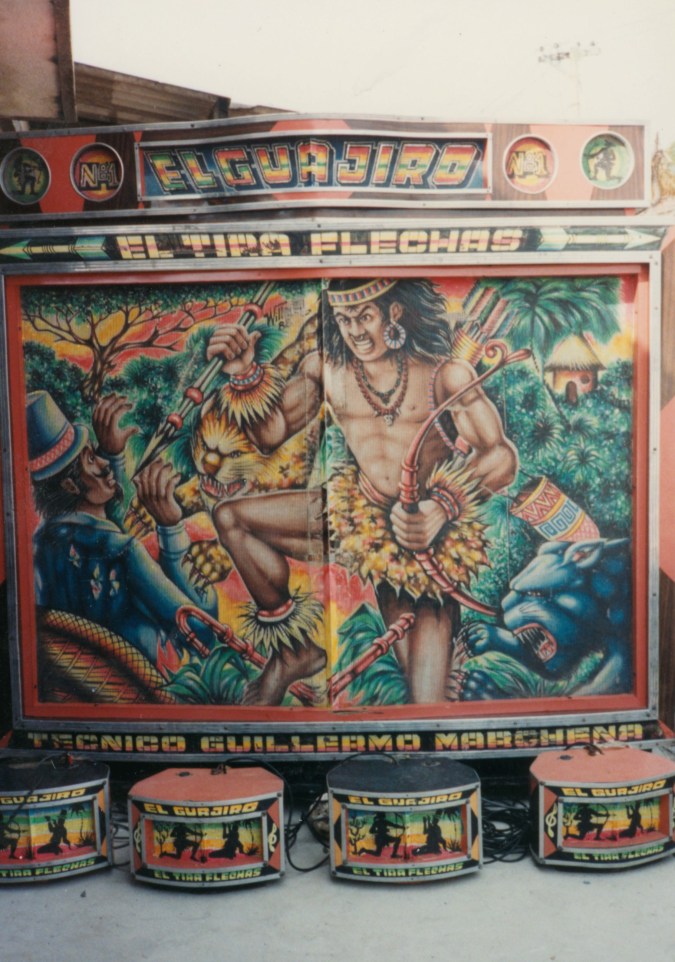

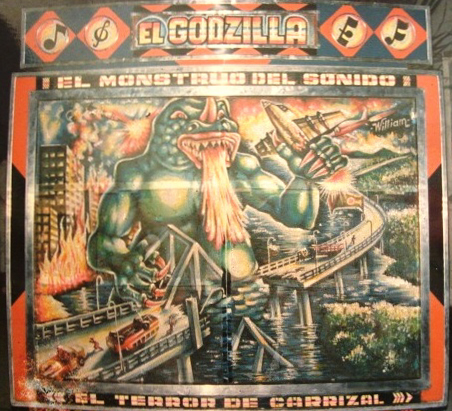

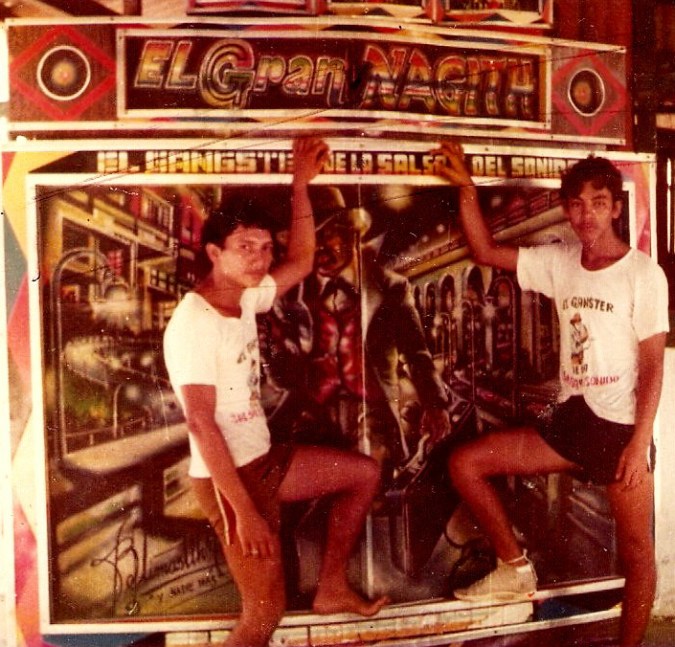

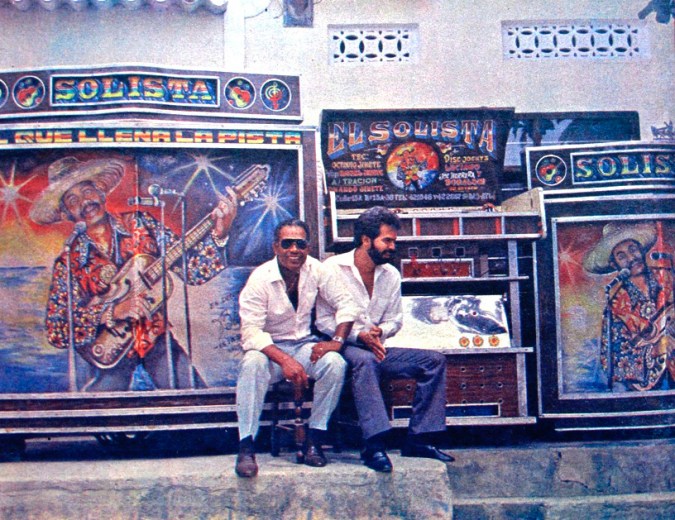

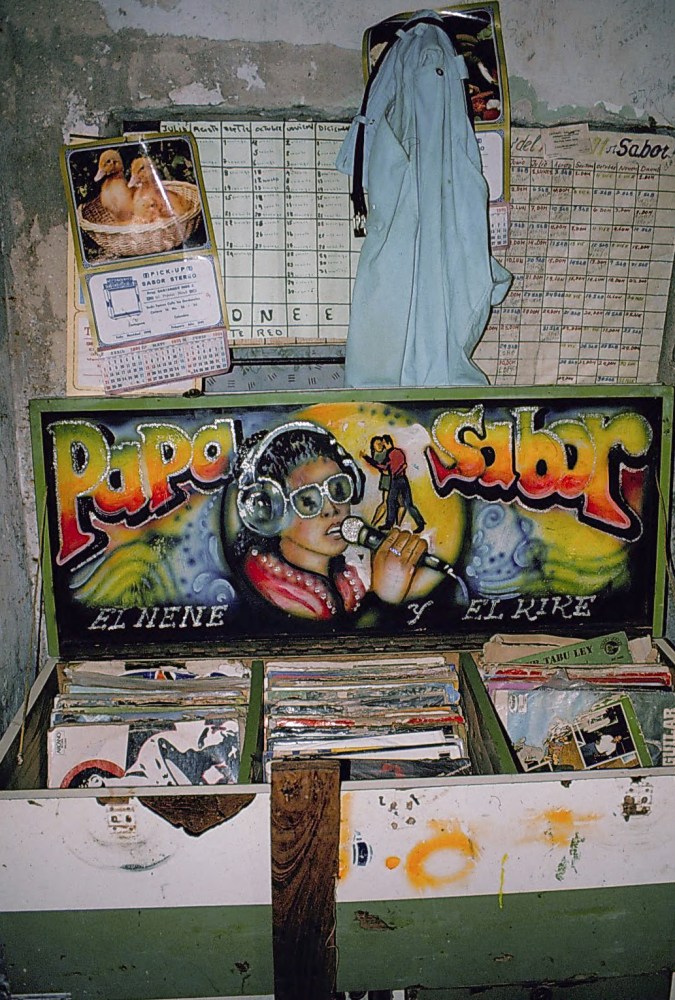

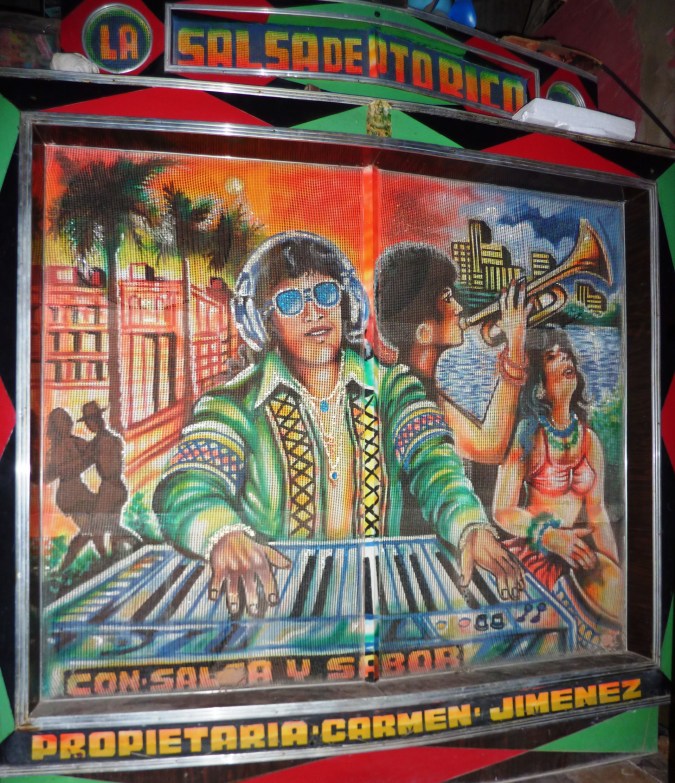

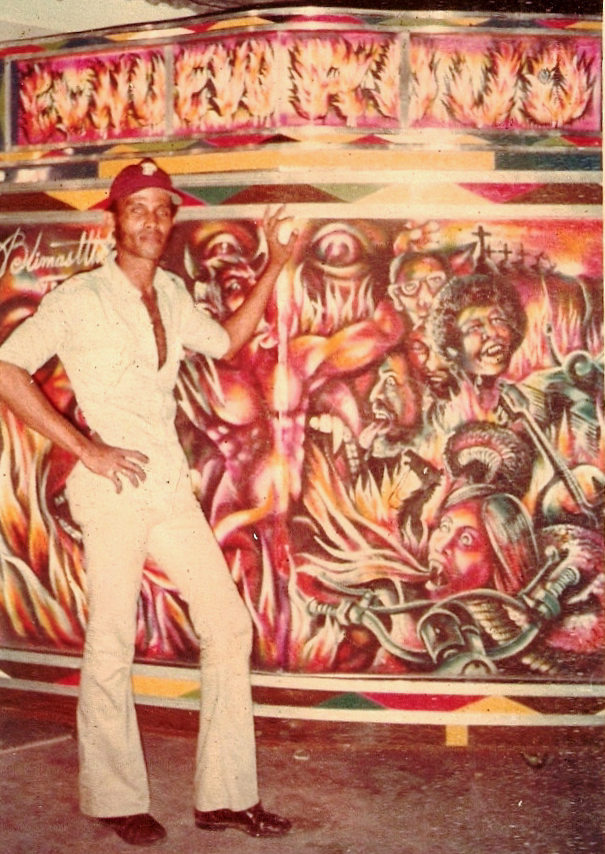

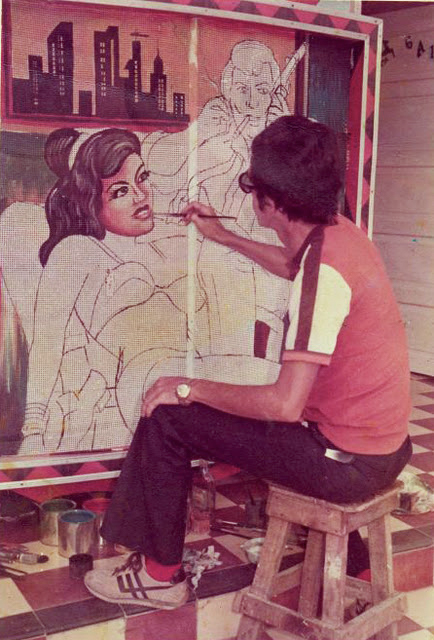

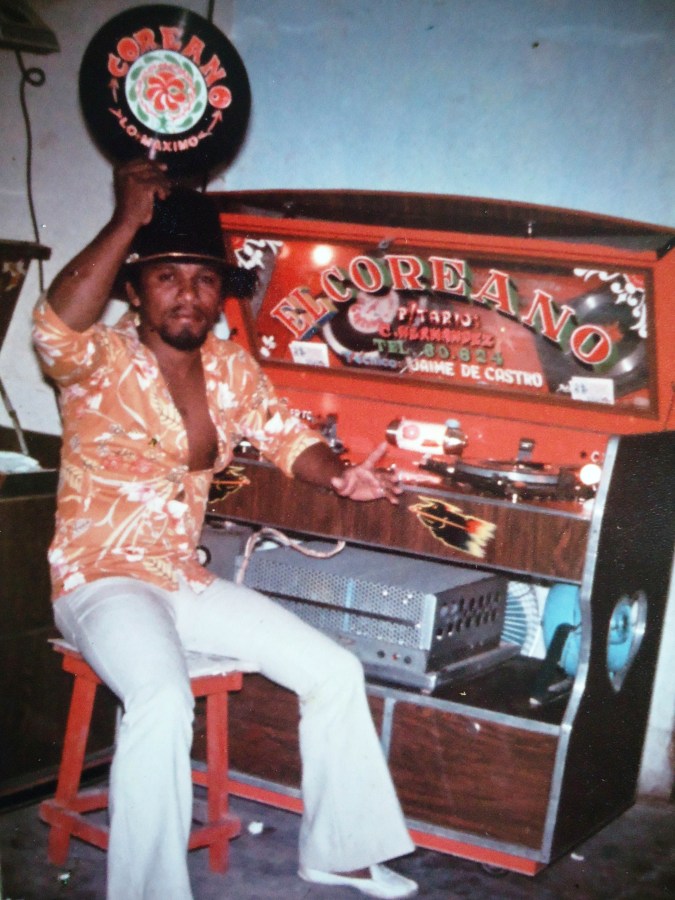

According to Altahona, the origins of picós go as far back as the 1930s, but it wasn’t until the 1970s that they became ubiquitous on the party scenes of Cartagena and Barranquilla. Special builders and sound technicians would construct towering wooden or Formica-lamented boxes around dual turntables and mixers. Then, Colombia’s best artists would paint the surface of the boxes with glowing illustrations, animating the sound systems and giving them each their own personality.

Playful battles often revealed themselves in the designs of the picó, which nearly always boasted flashy — even belligerent — pictures meant to outshine and eclipse other picós. Altahona has collected photos of picós emblazoned with neon Godzillas, fluorescent Rambos and grimacing warriors brandishing hefty bazookas — all signifiers meant to show that a picó was the barrio’s biggest and baddest. The images would usually give the picó its name: Partygoers might shout to each other that they were heading to El Gran Guerrero or El Dragon for a night of dancing.

“It’s a game of images and propaganda in the art, like telling the other picoteros, ‘I’m better than you. I’m number one and you’re number two, I’m the one everyone looks for. Women look for my picó and no one looks for yours.’ It’s a [type of] communication that only exists in the picó,” Altahona explained.

That same spirit of cheerful competition characterized the music as well. It’s no coincidence that the cities where picós have flourished are in close proximity to Colombia’s ports. Altahona says that ships would dock after trips to Africa, filled with records that offered a world of unheard soca, reggae, dancehall, and zouk rhythms. Picoteros would race to find rare vinyls that would set their sound system apart, popularizing African and Colombian traditions among costeños.

Picoteros would keep their discoveries a secret by scratching out the labels on records, ensuring other DJs wouldn’t be able to copy or access their tunes. They’d rename African songs something in Spanish — “Zangalewa,” the Cameroonian makossa hit that Barranquilla native Shakira readapted in FIFA’s “Waka Waka,” became known as “El Militar” among Colombians, for example. Many of the bangers that became popular exploding out of picós would eventually trickle onto the radio or television, sometimes reinterpreted by Colombian musicians.

“The picó is like an international radio station on the northern coast of Colombia, where you can hear different rhythms from every corner of the world,” Altahona said. “So many songs became hits in Colombia because they were popularized in picós.”

Over the years, Altahona noticed smaller sound systems, called minitecas, arriving in Colombia and inspiring picoteros to make their music players sleeker and more compact. But he remained committed to the picós of the past. Once he started collecting and sharing nostalgic images of picós on AfriColombia, his posts sparked global interest. In Colombia, picós have also had a renaissance, with many picoteros rebuilding their old boxes and celebrating the sound system’s golden years. Already, it seems those glory days aren’t over yet.

To learn more about picó culture, scroll though some vintage photos from Fabian’s AfriColombia archive below.