Welcome to Ponlo En Repeat where we revisit Latinx music history’s biggest hits, misses, and unbelievable moments; and how they impact our world today.

In 2020, “Lambada” seems like little more than a bleep in pop culture history; it’s hard to picture the massive worldwide phenomenon it was. While “Lambada” might be a dated artifact of the dawn of the ‘90s, at the time it was a cultural watershed moment, a global Latinx music hit when those were not as common as they are today, a bastion of public moral decency that reeked of classist and racist connotations, and an example of when a fad could be taken too far. Looking back, it’s far from a product of its time, since the discourse then echoes in cultural products of our time. To put it in context, picture the conservative media reaction to “WAP,” then imagine major motion picture studios releasing multiple films based on the song only to find out nothing about the song was real. It’s a wild ride.

The story at first seems pretty straight. Kaoma dropped the song of the summer in July 1989, a catchy Brazilian track accompanied by a racy video that made an instant impression. Soon enough, it was topping the charts in Europe, followed by Latin America, and finally, the United States when “Lambada” hit number one on the Billboard Hot Latin Chart and spent seven weeks in that position. It also peaked at number 46 on the Hot 100 in 1990 and ended selling 5 million copies worldwide. Quite the feat for a tune sung entirely in Portuguese.

“Lambada” is a catchy enough tune to propel it to number one, but it’s everything around it that pushed it to ubiquity. Like many modern chart-toppers, “Lambada” became a worldwide hit thanks in part to its accompanied dance, long before the internet–let alone Tik Tok–were part of our everyday routine. The dance in question involved squeezing bodies tighly, swinging hips in unison, and only separating for the women to perform spins to have their short skirts fly around; because of its sexual connotations, it was nicknamed (or marketed as) “the forbidden dance.” Most people came to know the dance through the video, starring two young teens, Washington Oliveira and Roberta de Brito (known professionally as Chico & Roberta) that helped fan the flames of controversy. Soon enough, talk shows and news casts debated the moral weight of “Lambada.”

It’s hard not to draw parallels between the comments made about the lambada dance and perreo. Both are considered sexually provocative dances that should not be performed in public. Perreo comes from reggaeton as danced in poor barrios, while “Lambada” can’t be divorced from the image of the favelas of Brazil, even if the video depicts the beaches of Bahía as its scenery. Latinx expressing themselves through dance that has not been approved by mainstream white and white-aspiring guardians of decency in Latin American countries has remained a hot button issue. In the video, Chico and Roberta are Black and white, respectively; while there’s no record of it, one can imagine that it caused some racist comments from pundits arguing against its “perverted” nature.

Sociological pondering aside, the more you look into it, the more convinced this was all orchestrated to maximum effect. Here’s the story.

One of the only true Brazilian aspects of “Lambada” is the dance itself. Aspects of it can be traced back to carimbó, a Pre-Columbian dance style that takes its name from a drum. It’s the only form of dance that the three ethnic groups of Indigenous people of the region practiced and contributed to. Portuguese colonizers added European influences to carimbó and centuries later, adopted cumbia and merengue movements to it, becoming lambada.

In 1981, a Bolivian folk group called Los Kjarkas wrote “Llorando Se Fue” based on an ancient Andean melody. The Afro-Bolivian saya ballad became a huge hit for them, inspiring covers all over the continent. In 1984, Peruvian cumbia band Cuarteto Continente covered “Llorando Se Fue” with an upbeat tempo and used an accordion as its main melodic instrument. Marcia Ferreira scored a big hit with her Portuguese translation of the song, becoming “Chorando Se Foi.” This version helped the lambada to become the big dance fad of the Bahia Carnaval in 1986. However, like most fads, it didn’t survive to the next year–and that would have been that if not for capitalism.

French songwriter/entrepreneur Olivier René Marie Lamotte d’Incamps had been visiting Porto Seguro, the city that had adopted lambada more fervently, and witnessed the music and dance first hand. Sensing that it would be a hit in Europe, he devised a plan. Associating himself with indie record label owner Jean Karakos, they assembled the group that became Kaoma, recruiting various members of the French-Senegalese Afro-fusion band Touré Kunda as well as dancers straight from the Porto Seguro club Boca Da Barra; the band was rounded out by French-Brazilian vocalist Loalwa Braz. Kaoma recorded a note-for-note cover of the Marcia Ferreira version of “Chorando Se Foi,” yet the label on the recorded credited a single songwriter, Chico De Oliveira, a stage name of d’Incamps (he was also credited as a performer under the name Olivier Lorsac). Shortly, the video was filmed in Bahia, recruiting Chico & Roberta there. The rest was history.

To illustrate the massiveness of “Lambada,” two major Hollywood studios rushed to release movies based on the song. In March 1990, Lambada and The Forbidden Dance opened in theaters. Both are Dirty Dancing knock-offs made on a low budget (and both lost money in the box office) made in order to seize the popularity of the song. Some have compared this phenomenon to the rock n’ roll exploitation films of the 1950s, but it bears mentioning since few songs in the last 30 years have inspired something similar.

Likewise, d’Incamps and company rushed to capitalize on the success of the song, releasing the full-length album Worldbeat in December of 1989. It features such varied tracks like “Lambareggae,” “Lamba Caribe,” and “Lambamor”–and if you guessed that all of these sound like lesser “Chorando Se Foi” soundalikes, then you are correct. Considering that “Lambada” is included on the album, Worldbeat sold great, but the follow-up single, “Dançando Lambada,” couldn’t replicate the feat. They even tried their luck with the kids in the video, recording an album of Chico & Roberta that failed to catch on. Furthermore, Los Kjarkas, Cuarteto Continente, and Marcia Ferreira (along with arranger José Ari) sued d’Incamps for copyright infringement. Eventually, the credits were split between the Hermosa brothers (of Los Kjarkas), Alberto Maravi (producer of the Cuarteto Continente version), Ferreira, and Air; interestingly enough, Billboard chart archives still list C. de Oliviera as the sole songwriter. Kaoma released two more albums, 1991’s Tribal Pursuit and 1998’s A La Media Noche to mild reception before breaking up. In a tragic twist, vocalist Loalwa Braz died in 2017.

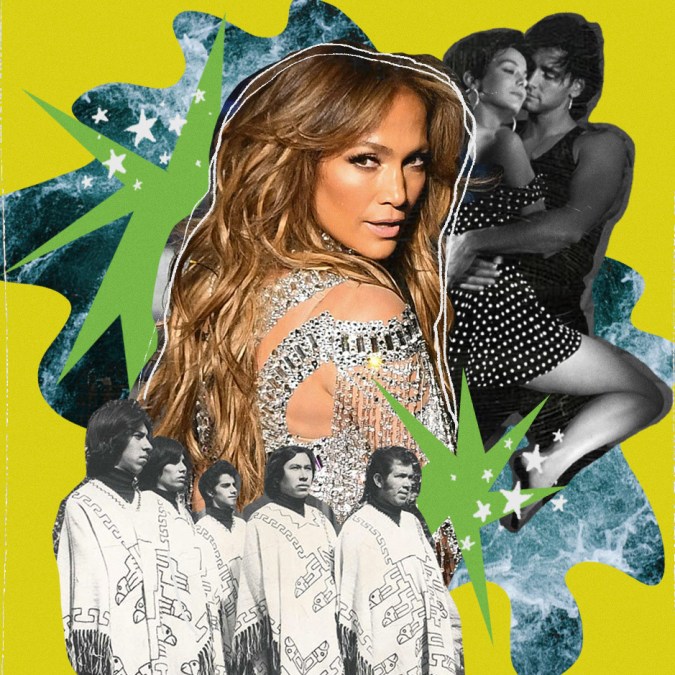

The team behind “Lambada” remixed, repackaged, and reinterpreted the song for years to try and squeeze the most juice out of it without finding much success. In recent years, the melody of the song is better known as a sample or interpolation, most notably on Jennifer Lopez’s “On The Floor” and Don Omar’s “Taboo.” Daddy Yankee, Wisin & Yandel, and El Alfa have also taken elements of the song for their own purposes.

On the surface, the era defining phenomenon known as “Lambada” may not be felt 30 years after its peak; yet it presaged a lot of the assumptions and exceptions the larger world can have about Latinx music while they push it to the stratosphere. At the very least, it’s one hell of a history lesson.