With additional reporting by: Joel Moya

Over two months after COVID-19 was officially declared a pandemic by the World Health Organization, the economic consequences brought by its spread and the health measures taken by governments globally have been all-around catastrophic. With a death toll that surpasses 400,000 and around eight million infected patients worldwide, it’s been an expected priority to ensure people’s health first, but the economic downturn is already being compared to the 1930s Great Depression.

The impact resounds in every level of the music industry, being the artists the most visibly affected. As quarantine and social distancing policies began to be enforced, thousands of confirmed tours and concerts were postponed or canceled in a matter of weeks, and artists took their struggles to social media, opening a window to the precariousness of music as a job and to how much they rely on live performances to ensure their income.

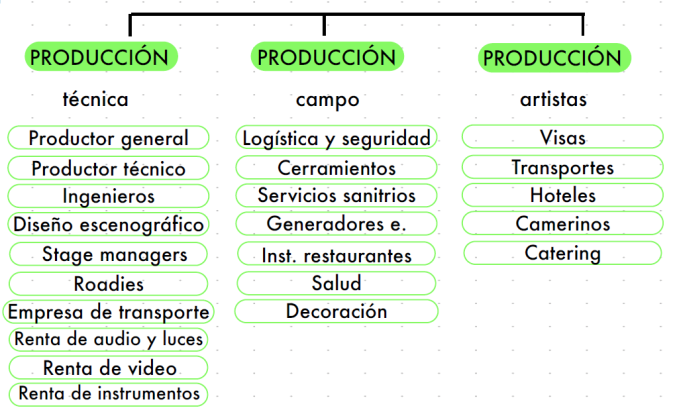

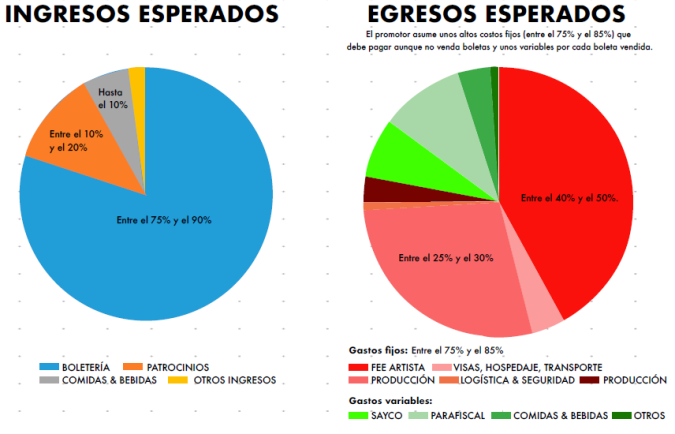

Behind every single one of these shows there’s an army of live music promoters who are now facing a grim scenario where their livelihood, which depends almost solely on masses of people congregating in a confined space, has been paused for the foreseeable future. Those affected concerts translate into important financial loss for promoters, having to cover expenses like non-refundable advances for artists or airplane fares and accommodation cancelations, while also having to refund tickets or putting them on hold as they attempt to reschedule.

Here at Remezcla, we reached out to a number of small and medium-sized promoters from Latin America, USA, and Spain, to learn more about the new reality the live music industry is facing regionally and their expectations for the future.

In Colombia, Páramo Presenta suffered one of the biggest early blows in the region’s massive events circuit, as they were forced to postpone their flagship festival Estéreo Picnic only a month before it materialized. “We’re lucky that the [COVID-19] situation has been global and everyone is experiencing the moment first-hand,” said Philippe Siegenthaler, talent buyer at Páramo Presenta. “In that sense, there’s been a big understanding and fellowship in the industry because we’re all in this mess together.” He is hopeful the festival will take place on its new December date, especially since its revenue represents a significant part of what the company needs to operate in the whole year.

Puerto Rico’s Buena Vibra also had something big on the horizon: two Bad Bunny concerts in May at the Hiram Bithorn Stadium in San Juan. Both dates are now rescheduled for late October and further event programming is currently paused. But Buena Vibra’s CEO Emil Medina highlights the real magnitude of the crisis by going further down the roots of the industry. From sound and light technicians to bartenders, there’s a whole ecosystem of workers who are simply unable to do their job right now. “They’re who we’re worried about the most,” he explains. “There will always be artists, but if you think about it, technicians and the whole staff behind them last many years, I’d dare to say even longer than an artist’s success.”

Initiatives like Far Away Together Festival, an online concert series organized by Mexican promoters like Nrmal, ECO, and Distrito Global, alongside El Día Después and Grupo Modelo, aimed to help artists and their staff through a crowdfunding campaign that ran in parallel to the livestreams. Also in Mexico, a new project called REMM was launched by venues, promoters, artists, managers, and bookers, to reactivate the live music economy by organizing paid livestreams of concerts performed behind closed doors. This concept was landed successfully by Duars Entertainment, producers of the recent Rauw Alejandro show at San Juan’s iconic Coliseo. Following rigorous health and safety measures, the concert featured a full setup, including lighting, visuals, and pyrotechnics, giving island workers the opportunity to be employed during the pandemic.

“It’s crazy, because in these moments you realize how many people depend on a single thing,” says Daniel Zawadzki, head of artist management at M3 Music (Bomba Estéreo, Mitú.) “I hope governments also aid those groups, because a band can do their thing [to earn money] but it’s unfeasible to support a staff for a year without being able to tour.”

Some governments have been able to aid their people with a number of economic measures mostly centered in loans, debt moratorium, or fiscal benefits. Commercial banks have also joined in with deferment of credit payments. But little-to-none of these actions are directed specifically to the live music industry, but to particulars or to the broader “small and middle-sized businesses” label. Companies like Spanish promotion and management company Ground Control have been able to access these public and private aids to keep covering their payroll, as well as Chile’s well-known promoter Fauna Producciones, who are also dealing with the repercussions of a national social explosion that erupted in November 2019 and continues to this date.

Still, the economic crisis has translated into important layoffs for many of these companies. Peruvian promoter Veltrac has been forced to reduce 60 to 70% of its team; in Mexico, Onda Mundial’s staff shrunk from 10 workers to only two; and Fauna Producciones are currently working with the minimum workforce needed to continue operating.

Although in many countries there are established guilds that gather live music companies, like ARENA in Peru, AGEPEC in Chile, FMA in Spain, and the newly-born CAPEMA in Costa Rica, José Velázquez, CEO at Veltrac, thinks the COVID-19 crisis has exposed the industry’s weaknesses as a collective. “The culture sector in Peru is very disjointed. We don’t have the organizations [we need] to go to the government in an orderly manner with correct information so it can be directed to a department and specific laws can be issued to protect us.”

This is also true for Joan Vich Montaner, managing director at Ground Control, who thinks, in his country’s case, the smaller, underground side of the live music industry isn’t represented in those guilds and organizations. “All those people have to be considered by the government so they can be included in the decisions,” he explains. “Sometimes the government says, ‘We’ve had meetings with the sector,’ and they’ve only had meetings with major labels, major festivals, major promoters, disregarding the smaller ones.”

Comprehensive reliable data is showing its real value during these times, and promoters will certainly pay more attention to their numbers, particular and collective, moving forward. Páramo Presenta has been in constant communication with Colombia’s presidency and Congress, as well as with Bogota’s local government, sharing data that shows the live music industry’s economic impact on a large-scale level, with the hopes to land the help they need to keep it alive.

All across the board, the biggest obstacle the industry is facing is uncertainty, as promoters are unable to know how the future will look like for live music so they can plan their next steps accordingly. But it’s far from the only hurdle they’ll have to jump.

Vich Montaner points out the lack of vaccination against COVID-19 as a major obstacle. “Even if we’re told we can do concerts, if there isn’t a vaccine, what we’re actually being told is, ‘You can now allow people to get together and get sick,’” he explains. “On one hand, I want to do shows, but on the other one, I don’t want the disease to have a new spike. 30,000 people have died in Spain.” South Korea’s new outbreak, after reopening clubs and bars, is an example of a scenario promoters don’t want to replicate.

The economic crisis brought on consumers by the pandemic is another potential challenge. “I don’t think there’s anyone right now who can measure how they’ll come out economically from this situation,” says Siegenthaler. “We don’t know if people will be willing to pay the same amount they used to pay to go to a concert.” Parra agrees: “How deep in debt will people be after all this? How much unemployment will there be?” he wonders. He considers, as part of his future strategies, the possibility of organizing shows that cater to an older, more financially stable audience who will be able to still spend money on concerts.

Other issues raised by the interviewees are related to migratory movements and airlines in the future. Colombia’s Avianca recently filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy in the United States, and after 1,400 layoffs, LATAM recently followed. Zawadzki also predicts strategic partnerships will suffer. “I think brands that sponsor festivals or tours, or that pay for sync [licenses], will have big cuts in their budgets because everyone is now focused in selling and securing everything they can, because nobody knows how long [the situation] will last.”

For now, these promoters are thinking outside the box in order to keep the ball running during these hard times. René Contreras, from Viva! Presents and Goldenvoice, is using this time to research and reach out to independent music projects from Mexico, sharing his findings through his Dublab show Oh No It’s Monday. Ground Control and Argentine promoter Indie Folks have also focused on the label side of their business, favoring local artists not only with their platform, but also with their emotional support and encouragement.

Fauna Producciones are deep into financial restructuring to keep their machinery running during the following months. Onda Mundial’s radio transmissions are still active, and so are their publishing efforts. Buena Vibra, besides turning to merch and social media promotion, are exploring the possibility of working even closer with artists, joining them in their studio process to influence the outcome.

The proliferation of streamed concerts through platforms like YouTube or Instagram has been an emergency response to the impossibility to hold live shows, but the interviewees agree that they won’t be viable long-term until an effective way to capitalize on them is found. Ground Control championed one of the first online festivals made during the quarantine, aptly named Cuarentena Fest, and to Vich Montaner, it was a success in every aspect, except money-wise. “We added a PayPal button [on the transmissions] and it proved to us that people aren’t really willing to pay for streamed shows. I guess it’ll change in the future.”

Páramo Presenta have held two editions of their own digital festival, Unión, an idea they had been considering for years but was finally precipitated by the pandemic. “It has its challenges and limitations in terms of how it’s consumed and how brands understand it,” explains Siegenthaler. “It still doesn’t feel like audiences are willing to pay for content like this one, because people are largely used to receive free content online.”

As some countries begin to relax some of the measures, the possibility of bringing back live shows is starting to emerge, but not without restrictions. News of alternatives, like socially-distanced events and drive-in concerts, are more frequent, as well as government decisions to let selected venues operate at a reduced capacity. For the interviewees, creativity is key in these convoluted times. Witnessing the success of events held through video games like Minecraft and Fortnite, Onda Mundial’s Lucía Anaya is particularly excited about the potential VR can bring to the live music industry. She and Vich Montaner also predict an emphasis in smaller, more exclusive events or “experiences,” although the latter fears this could result in a more elitist business.

All of the interviewed promoters sense that the live music industry will no longer be the same, and they try to picture how that “new normal” ahead of us will look like. Parra believes the power of community will make the industry move forward. “I think a more collaborative future is coming. Before, everyone was trying to impose what they wanted to prove or reflect,” he shares. “More collaboration will mean lower costs, less competition, and probably higher income.”

Nobody has the right answers, and not even the large monopolies are safe from the crisis. For promoters, this is a time to patiently observe and recalibrate their plans as every day goes by and the situation develops.