For Roger Miret, living on the margins wasn’t just a lifestyle. It was his life.

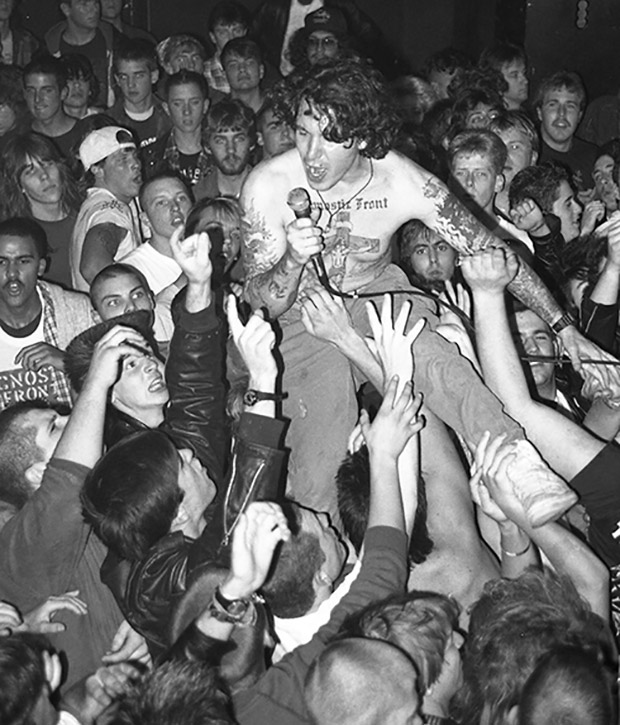

As the lead singer of seminal New York Hardcore band Agnostic Front, he helped shape the identity of a downtown scene of misfits and outcasts, influencing future generations of hardcore kids, as well as the likes of thrash metal bands like Metallica and Anthrax.

As a young child in Cuba, he fled the Castro regime with his mother and siblings, landing in Paterson and Passaic, New Jersey. His mother struggled to make rent working exploitative jobs; they would save money by making soup from pigeons he caught in the park. Miret witnessed his mother’s abuse at the hands of different men, his accumulated rage later manifesting itself in his music.

He nonetheless occupied a unique position as one of the few Spanish-speaking Latinos among the gang of hardcore kids that clashed with Puerto Rican gangs on Manhattan’s Lower East Side in the late 70s and early 80s. The relationship could even be symbiotic — in need of cheap promotion, Miret and the band would pass out Agnostic Front T-shirts to the homeless, clothing needy people in the process. His path was just one of many in the diaspora, an example of the influence Latinos have had on American culture that often goes unnoticed.

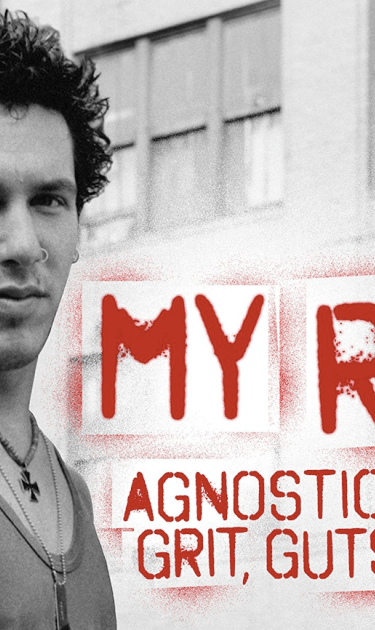

What follows is the first chapter of his memoir, My Riot: Agnostic Front, Grit, Guts & Glory. “From Cuba with Love: The Struggle of an Immigrant in a World of Hate” details his flight from Cuba and his turbulent and violent relationship with his family, the foundation for the life he would lead in at the vanguard of New York hardcore. The book is scheduled for release on August 29, 2017, on Lesser Gods.

Editor’s note: The following chapter contains depictions of domestic abuse, war, and violence.

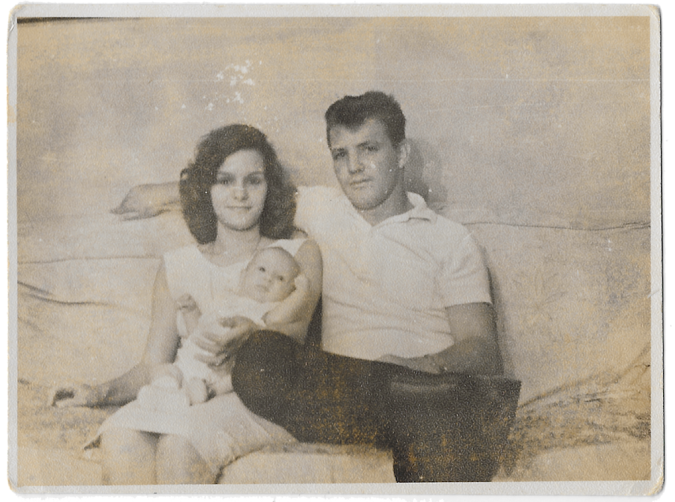

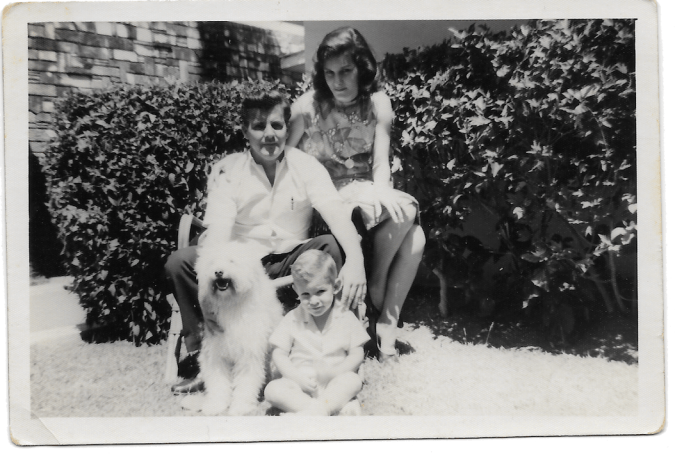

“My mind is like The Wizard of Oz. My earliest memories are in black and white. Later they turn vivid and colorful. But some of my happiest recollections are the least distinct, like an old, flickering silent movie filmed before the age of high-definition images and dazzling special effects. The first thing I remember is being with my dad, Rogelio, on a rocky beach in Havana in the late 60s. We lived in a two-story house with a balcony, and I was running up and down the sand with my sheepdog, Chuchi. We were surrounded by towering cliffs. The sand was white and the buildings were gray. Those were happy days. They didn’t last. Once the technicolor kicked into my brain a couple years later, life was a battle.

“We had no idea we were heading for America or what would happen when we got there.”

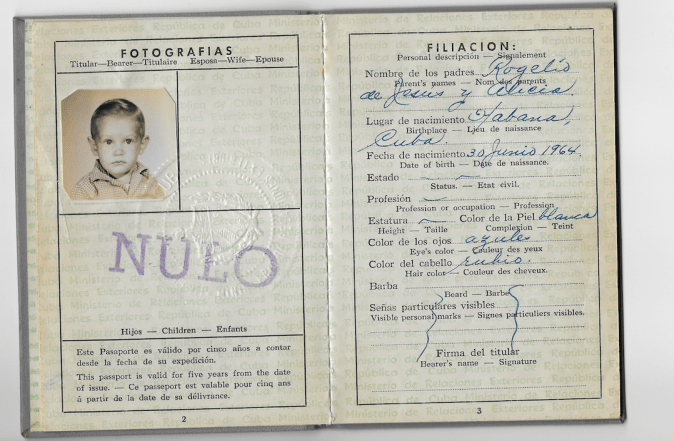

Everyone on my father’s side left Cuba because they felt threatened by the Castro regime. My uncle Leo married an American woman, my aunt Betty, and was the first relative to go to the United States. My mother, Alicia, married my father when she was 15. I was born on their one-year anniversary on June 30, 1964, in a birthing clinic in Havana called Clinica Hija de Galicia. By the time my mom was 20, she had three kids — me, my brother Rudy, who is two years younger, and my sister Mayra — who was born a year after Rudy.

We weren’t old enough to know why we were leaving Cuba; we went wherever my mother took us. We had no idea we were heading for America or what would happen when we got there. We just knew we were moving away from home. We got on this old Pan-Am airplane and the pilot pinned little blue wings onto our shirts. That eased my fears somewhat. I looked out the window and saw the clouds, which was incredible. Today, hundreds of flights later — to and from Europe, South America and Australia — I’m not as impressed by fluffy white clouds.

The first stop for my family back in 1968 was Miami International Airport. We debarked and took a bus to a processing center at Opa-Loca Airport, which was like a refugee camp. We waited for hours to be processed, then flew to Kennedy Airport in New York. We were free — from Cuba, at least.

My uncle Leo picked us up in his 1963 four-door Buick and drove us to his thirty-eight-story building in Elmhurst, Queens. I had never seen anything so tall, even on television. It looked like it went straight to heaven. All the buildings seemed huge. Nothing in Havana was more than a few stories high. The skyscrapers were so tall I thought there must be giants living in them.

Once we washed up and ate, we drove to East Paterson, New Jersey, and met my father’s side of the family. Since Leo was married to Aunt Betty, an American, he was able to bring his brothers and sisters over. The other relatives who greeted us were my grandfather Rafael, my grandmother Josephina, Aunt Clara, Uncle Ralph, Aunt Margarita, Aunt Amparito, Uncle Miguel and my cousins Betty Ann, Leonard, Clara, Sheila, Ralph Jr., Alex and Olgita. There were a lot of people in the room, and I was kind of freaked out — partially since I expected those giants to walk out at any minute. At the time, I didn’t even know New York had a football team called the Giants! Everyone in my family was friendly and welcoming, but they overwhelmed us with questions.

Weeks later we were still figuring out what to make of our situation. (By that point, I realized there weren’t any giants.) Around that time, my dad got shot by anti-Castro freedom fighters. He and my uncle Albert weren’t on duty, but they were wearing their military fatigues and were in the wrong place at the wrong time. A gunman burst into a bus and opened fire. My dad and uncle were hurt pretty bad. They both survived, but I think my dad suffered from post-traumatic stress disorder. He was never the same.

“I find it strange that American Cubans don’t like the native Cubans.”

In New Jersey, I spent a lot of time with my grandfather Rafael, who was a gentle and loving man. He was a Freemason and told us stories about their symbols and rituals. He showed me a book about the Freemasons with his name inside. Apparently, he was the first or second of the higher-ups in the movement, and although I didn’t know it, when we came to America we were under investigation by the CIA because there was a lot of misunderstanding about what the Freemasons represented. They thought we might be communists, especially since we came from Cuba. That was my first exposure to politics. I was just a kid, and I didn’t know anything about Castro so he was never a threat to me. But everyone on my dad’s side of the family was anti-Castro — definitely not communist.

My mom’s side included a lot of guerillas that supported the revolution and the Castro regime. My mom was the only one in her family to leave Cuba. She came from a family of six kids. Her mother, Esperanza, was a guerilla insurgent, as was her husband. Since they were always on some secret mission or in hiding, my mom was raised by her sister Julia, whom we called Grandma because we never knew Esperanza. One of my mom’s brothers, Filiberto Jr., became a famous model in Cuba and one of her sisters, Dulce Maria, was a successful actress. Maybe performing was in my blood. In contrast with a lot of my mom’s family, neither Dulce Maria nor Filberto Jr. were political and they weren’t fighters. Decades later I became a little bit of the former and a whole lot of the latter.

It’s weird that almost everyone from my mom’s side of the family is still in Cuba and my dad’s side is all here. I find it strange that American Cubans don’t like the native Cubans. I always viewed everyone as the same growing up, though other people definitely saw me as Cuban. I kept my Cuban citizenship until 2006, when I became an American citizen.

As a little kid, New York seemed strange and wild to me. One time when we were driving through the City with my mom and Uncle Leo, I saw two men passionately kissing. They were really going at it.

“Look, mom! Look, look, look!” I said.

“Don’t look! Don’t look!” she replied, then covered my eyes. That was my first exposure to homosexuality. She wasn’t about to explain it to me.

Growing up in the slums of New Jersey towns like Passaic and Paterson was a struggle. We never had any money. My mom worked at a local meat packing plant since she wasn’t trained to do anything else. Before my dad came to America, she was all alone. Even though she had a job she could never afford the rent. Once or twice a year we’d get evicted, then we’d have to pack up and move. Because I never planted roots I didn’t have any real friends. I was a shy kid, so I wouldn’t make friends until my brother Rudy, who was more social, met kids. I tried to make friends with his friends, but by then we were usually moving again. After that happened a few times, I became closed off and introverted. Life was pretty shitty. My memories from this point on are more focused, in high-definition color and as sharp and harsh as could be.

“I can’t condone what my dad did to my mom. I fucking hated it.”

We lived on welfare. We had food stamps and federal assistance because my mom was 20 years old and raising three kids by herself. She was embarrassed about taking money from the government, but we needed it. That’s why I still believe in the system when it works. She had to feed us and the government helped make that happen. Say what you will about how corrupt and intrusive the government is, but we wouldn’t have gotten by without the welfare system.

We didn’t own much, not even a toaster. If we wanted toast, we’d light the stove, put bread on it and then flip it over so both sides were cooked. We’d put some sugar on the toast if it got burnt. We couldn’t throw it away and get another piece of bread because there was barely enough to go around. We scraped off the burnt crumbs and made it taste as good as possible. There was no waste in our house.

No one on my mother’s side of the family was into music. No one played an instrument or sang. I didn’t listen to much music when I was really little — not even the radio. My father came to live with us two years after we arrived, and he was infatuated with Mexican music. He didn’t care about Cuban music, but he’d blast classic rock and mariachi. My dad was obsessed with anything Mexican. When he died in 1994, I put a Mexican sombrero in his coffin. He would have liked that.

Even though my dad had family around when we were growing up, he wasn’t happy. The military got the best of him. He had insomnia, and when he was able to sleep he had horrible nightmares. He drank a lot, became an alcoholic and was abusive. Sometimes at night I’d pretend to be sleeping and I’d hear yelling, then the banging sounds of him pushing my mom against the wall. Smack! She’d cry or something would crash, and she’d fall to the floor with a thump. Then silence.

I can’t condone what my dad did to my mom. I fucking hated it. But he never physically abused my siblings or me. He took all his anger out on her. I think she purposely shielded us from him by becoming the target of his violence.

Shortly after my dad joined us in New Jersey, he got a job at the factory where my mom worked. They hired as many immigrants as they could and paid them next to nothing. One day my dad had an accident while working with a machine that chopped up chickens. He wasn’t paying attention. The blade came down on his hand and cut off four of his fingers. He shook his forearm and blood spurted from his mangled hand like water from a sprinkler. It splashed on the metal machine, and crimson rivulets ran down the chopping blade. Someone got a towel and wrapped my dad’s hand in it. He held it tightly as the white cloth turned red, but he didn’t scream or freak out. Either he was in shock or he didn’t care too much about losing a few fingers. He went to the infirmary, got stitched up and went home. Maybe somebody got four fingers in their wrapped package of deboned chicken breasts that week.

Since he was an immigrant, he didn’t get worker’s compensation and as soon as his hand healed he went right back to the plant. The place was dirty, it stank and it was hazardous. There were no safety regulations, and employees who got hurt were replaced by the next desperate people in line. That’s the way life was for new immigrants. My dad hated the factory, and he didn’t work there for long. It wasn’t because he quit. My mom left him.

“That’s the way life was for new immigrants.”

She met a Colombian man who also worked at the plant. He put on the charm and she fell for him. Soon after my mom started seeing him, my dad lost it. I don’t know how long it took for him to catch on, but one day he walked in on the two of them. My future stepfather climbed out the window and ran away while my dad went nuts. He stormed into my sister’s room and yanked the carpet. All the furniture went flying. The noise didn’t stop; it sounded like he was trashing the room. He wouldn’t stop screaming and swearing in Spanish. Then he grabbed my mom by the throat, choked her and banged her head against a metal heat pipe until she was unconscious. He kept yelling, but when he realized he might kill her, he let go and tossed her aside like a broken mannequin. Her forehead was cut and her nose was broken and bloody. The black eye didn’t appear until the next day. The neighbors upstairs called the police.

When my mom regained consciousness, she refused to press charges, but the police took my dad away in a paddy wagon anyway. There was a law that if the police showed up at a domestic violence scene, they had to arrest somebody. That was the last time I saw him for a while. I think my dad wanted to make up afterwards, but my mom had had enough. He moved to Florida and I briefly thought that might eliminate the crazy drama in our lives. We had a better chance of outrunning our shadows.

Violence was often part of the picture one way or another. I almost killed my brother one afternoon when we were hanging out in an apartment in Passaic, New Jersey, and my mom was out shopping. Rudy and I used to wrestle and play-fight. I’d pin him and rub his face against the ground. I was bigger and stronger, and that infuriated him. One time we were fighting and he was so mad that he started chasing me around the house. I ran out and slammed the storm door behind me, and he went through it with a horrifying crash. It sounded like someone had taken a bat to a giant window. Pieces of glass ripped open his neck, arms and legs. He lay on the ground screaming as blood poured out of dozens of wounds and gushed from a huge gash in his throat. A neighbor across the street saw what happened and told me to call 911.

While we waited for the ambulance to arrive, the neighbor tore up pieces of cloth and tied them like a tourniquet around Rudy’s neck. I was terrified because my mom wasn’t home. I thought, Oh, my God! If she comes home and sees all this blood I’m going to be in so much trouble!

The police took Rudy to the hospital, and his heart stopped while the doctors worked on him. They were able to revive him with a defibrillator, but he almost bled out. If it wasn’t for our neighbor, Rudy would have died. He needed stitches inside his neck and across the carotid artery, which had ripped open. But he survived.

“Violence was often part of the picture one way or another.”

Not long after Rudy recovered, my mom married my stepfather, which planted the seeds for a garden of new scars. My stepdad wasn’t as mentally unstable as my father, but he was a lot meaner, especially when he was drinking — and he liked to drink. I guess my mom saw something in him — mainly the fact that he wasn’t my father and he wasn’t beating her…yet.

With my mom and her new husband both working, our financial situation improved, but we still lived in a ghetto. The thing is, I didn’t know how poor we were. To me, that life was normal. It’s what I knew. I was with my family, and I had a roof over my head. Everything seemed okay. As a kid, you only know what you’ve experienced, so even when my stepfather started smacking all of us around, I didn’t realize that most people didn’t live like that.

The first time I realized I grew up in a ghetto was when I was older and I went back to visit. Driving through the dodgy streets and looking around and at the crumbling buildings, I thought, Holy shit! I lived here?“

Update, 8/25/2017 11 a.m.: A previous version of this post characterized the people living in a halfway house above CBGB’s as homeless. This post has been updated with a clarification.