Dominican dembow rose out of the barrios of Santo Domingo as a sound and movement based on the Dembow riddim – yet independently of reggaeton’s almost parallel sound. Once a marginalized and maligned genre in its home country, dembow gradually gained acceptance from the Dominican urbano community. Even though it’s now closer to the mainstream, the genre is still in relative infancy – with new proponents and fans spreading the sound across the globe. Si Tú Quiere Dembow is a new monthly column by Jennifer Mota that will explore the genre’s history, while also spotlighting the leaps dembow takes on a daily basis.

In 2011, just as waves of dembowseros like Doble T y El Crok, Mr. Manyao, Secreto and El Alfa began to solidify the emerging dembow scene, rapper Pablo Piddy made a transition many of his peers couldn’t have foreseen: He crossed over to Dominican dembow.

Though dembow saturated barrios and night clubs within Santo Domingo, it was not enough to impress hardcore rappers. Yet Piddy understood that Dominican consumers wanted dembow, and to push the movement forward there had to be unity among both sub-genres – hence he crafted the track “Si Tu Quiere Dembow.”

Since the 2010s, the sub-genre transcended Dominican media – becoming the face of the country’s urbano scene. Its momentous rise was a mix of organic enthusiasm coupled with ease-of-access to digital services like YouTube and Instagram – creating viral sensations. But dembow faced multiple obstacles, the biggest being the lack of support once received by established rappers who wanted no association with dembowseros and their producers. As artists who once were the genre’s biggest critics – like El Lapiz Conciente, Kiko El Crazy and El Fother – began to seamlessly dive into dembow, one can’t help but remember the “No To Dembow” campaign of a few years back.

“For me, it was a time where I saw many colleagues doubting my ability as a producer,” tastemaker Bubloy shares with Remezcla. “Those that didn’t believe and looked at it as junk and disposable music are doing this kind of music for their success today.” Known for El Alfa-definitive tracks like “Gustoso” and the remix to El Alfa’s “Coche Bomba,” he recalls the time when much of urbano gave these artists the cold shoulder.

Yet Bubloy trusted his vision. “Those things happen when you are the creator of something peculiar – always marginalized at first,” he says. The producer stuck by the movement knowing he was well-prepared to create all kinds of sounds, having already demonstrated it with prior dancehall riddims, rap and multi-genre-infused tracks. “The acceptance and happiness of the Dominican people, the fans – that for me was enough to ignore the discrimination of the industry,” he adds.

Though rappers gave dembow no more than a year before they thought it would inevitably fizzle out, the movement continued to grow and conquer party spaces. The “Say No To Dembow” movement came from broth conscious and street rappers, along with their followers, who often looked down on dembowseros. But why? For one, recycled loops and repetitive lines were not seen as “real” music. This was best exemplified on Dkano’s “El Bolo Bolo’ (La Historia De Un Dembowsero Cualquiera), a fictitious story of the rise of a dembowsero who easily creates a track off of random words like “bolo bolo.” Another concern many rappers expressed was that they would lose their identity because of a song. Dkano raps “Cuando lo presentaron, comenzó el problema le cambiaron el nombre, por el nombre del tema.”

Dkano was not alone in his sentiments. The father of Dominican rap, Lapiz Conciente went on to express his annoyance on “No Dembow-Masacre al Dembow” where he raps “el pais esta avanzando y el dembow lo está atrazando” adding to the belief that dembow was delaying the progression of the urbano community. The late Cirujano Nocturno and El Fother also condemned the music on “El Regreso del Hip-Hop,” where he rapped: “Que hago con vocear “ratata ratata” en una pista de dembow debarata,” explaining that he had nothing to gain with screaming on a broken, “messy” track.

The Dominican government’s history of banning sexually explicit music didn’t help either. The National Commission of Public Spectacles and Radiophony regulates content played on TV or radio and has banned songs by El Alfa, Chimbala, Nene La Amenaza and La Materialista in the past. “Sometimes you see that they prohibit a song or put censures on almost insignificant words while swearing words by international artists they leave without any censorship, and I think it is not fair,” says Bubloy. This was a topic of conversation discussed in a round table by Listin Diario in 2016, where similar frustrations were expressed by producers Chael Produciendo, Light GM, Nico Clinico, T.Y.S and Cromo X. The bunch also expressed the government’s interventions, clarifying that the government offered to help the urbano community and never followed through.

Three years later, Cromo X is self-assured that the commission’s obsession with urbano is nothing to be phased by. “As a producer, it doesn’t affect me [now]. Last year they banned two songs: “Matica y Traga” and La Insuperable’s “Me Subo Arriba,” he says, adding, “Urbano’s growth is currently depending on new facets of the internet and streaming not TV, radio and unconventional mediums.”

The anti-dembow campaign led by artists and the government’s intention to silence dembowseros only further fueled artist’s fight for recognition. The heated feud between El Mayor and El Alfa encouraged a change in delivery integrating sharp punchlines and witty phrases. Not to mention the rise of Latin trap and the creation of “trap bow,” which concluded a new era – one that mapped out a new format in the homegrown style, birthing songs like El Alfa’s “Dema Ga Ge Gi Go Gu” featuring Bad Bunny (a success that led to the creation of “La Romana.”)

With El Alfa, Chimbala and Lirico en La Casa’s international success, others began to look at dembow as a way to connect in the music industry. Today we see ex-El Army members like Bulova and Kiko El Crazy gaining momentum in the genre. For 12 years, Kiko El Crazy created music and never seemed to make the hit to take him over the edge. Following the advice of El Alfa, he started making dembow and became DR’s current dembow ambassador in three months. “The change happened when the industry began to see dembowseros and producers with great success, with successful tours, an increasing number of fans and the acceptance of the genre in foreign countries,” says Bubloy.

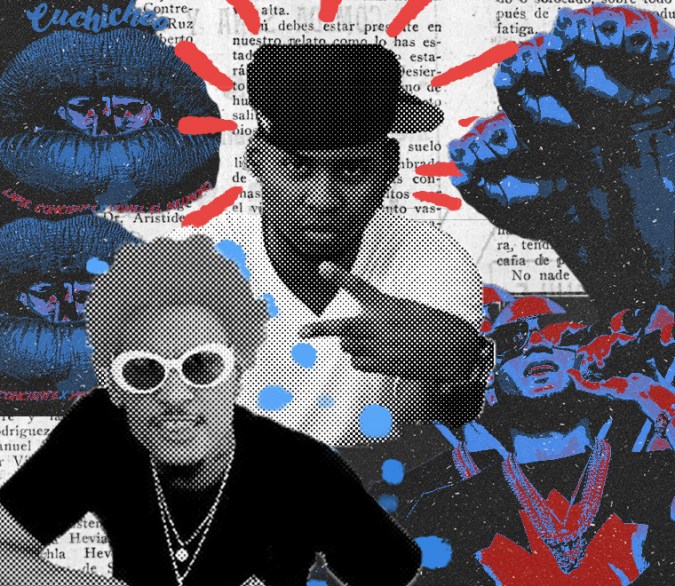

This past September, Yomel El Meloso dropped “Cuchicheo” featuring El Lapiz, where he started with “yo traigo un dembow no traje un trap.” A line that six years ago would have been unimagined. A few days later came “LA PAMPARA” by El Fother, Junior LOMI and Mainy Woo following the success of his summer hit “La Calle Es De Nosotro.”

The current dembow scene is perhaps the most vibrant and gritty the country has witnessed since it’s beginnings. With rappers like Rochy RD, Quimico and El Fother uniting, uplifting both el hip-hop Dominicano and dembow, 2020 is bound to be dembow’s year. As the new decade begins, it’s important to look back at the 10 years that solidified Dembow’s organic rise and the hurdles it faced, from its own community and native country.