“About 20 or 22 years ago, I met this kid named Brian Warner, who everyone knows as Marilyn Manson. He hadn’t yet become Marilyn Manson. But he was a very studied character. And he was so hideous that I thought he was a fantastic work of art, and that’s exactly what I told him: ‘You’re just so hideous, you’re beautiful, and I would like to take pictures of you,'” says photographer Theresa Kereakes, as she laughs sweetly over the phone.

Kereakes is describing how she approaches musicians, and how she was able to capture the soul of her subjects without exploiting them. With a career that spans over 40 years, Theresa was one of the first photographers to document the punk rock scene in Los Angeles and to highlight Latinos, women, and musicians of color. Looking through her work, you’ll find the first photographs ever taken of The Bags, The Zeros, The Go-Gos, the Deadboys, Joan Jett, Blondie, Suicidal Tendencies, The Gun Club, Kid Congo, The Germs, and The Alley Cats.

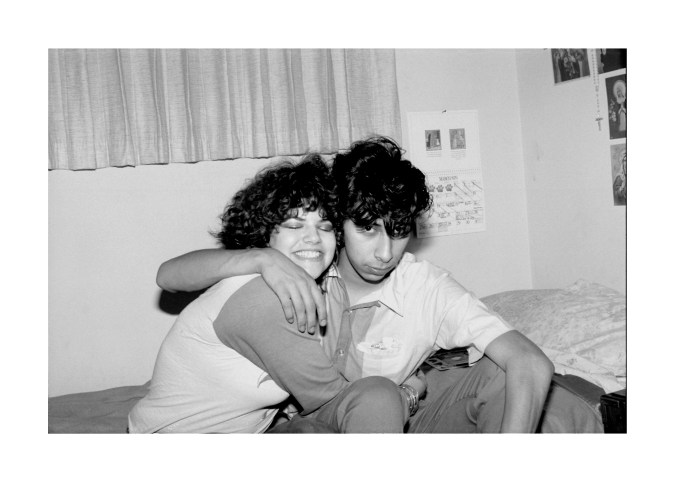

In the late 70s, Kereakes and her friend Pleasant Gehman of The Screamin’ Sirens started a zine called Lobotomy. Lobotomy was a punk staple carried at record shops across Los Angeles. In it, Gehman and Kereakes interviewed and photographed every punk act that came into town, from The Clash to Billy Idol. The interviews were conducted in Kereakes and Gehman’s apartments, The Tropicana Motel, and on the city streets. Lobotomy captured the texture of what the punk scene was like in the 70s; each photograph and article is candid, unrehearsed, and relaxed against a gritty backdrop.

Theresa’s work was on the frontline of punk, capturing a moment that would have otherwise gone undocumented.

There is a photojournalistic quality to Theresa’s work, and she is one of punk’s earliest documentarians. You could say that like Dorothea Lange and Margaret Bourke-White, Theresa’s work was on the front line of punk, capturing a moment that would have otherwise been lost.

When reflecting on her inspiration and the women photographers that informed her early work, Theresa says, “While I really liked Annie Leibovitz and everything she did for Rolling Stone, when Rolling Stone was really counterculture in the 60s and early 70s…the women photographers who were much more appealing to me from day one were two really famous ladies who worked during the Farm Security Administration during the Depression: Margaret Bourke-White and Dorothea Lange. They took all of those iconic pictures of the farmers leaving the Dust Bowl heading towards California. And also Diane Arbus, because she was completely enthralled by freaks, and the freaks themselves trusted her.”

Yet Diane Arbus has garnered her share of critics, as the subjects of her images notoriously despised her work. In one of her more famous photographs, Puerto Rican Woman with Beauty Mark, NYC, the subject had no idea that she would be photographed unflatteringly, or that Arbus saw her as a freak. Arbus also took photographs of little people, the disabled, and giants as part of her “freak” series, which spurred controversy around her work. While Arbus’ photographs are stunning, grotesque, evocative, and often empathetic, her work has been historically derided as exploitive of its subjects.

In many ways, Arbus’ photographs act as a foil to Kereakes’ images. The subjects in Theresa’s photographs show great vulnerability; however, Theresa never used her subjects to tell her own preconceived stories, or to manipulate them.

“What I’m doing is: Let me capture 1/125th of a second of your story,” she explains. “I think if the subject is really the subject instead of a prop, then it’s much more interesting and compelling.”

Her subjects were so much more than props, and her early photographs are a respite from today’s age of celebrity and tabloid culture. Instead, Theresa knew her subjects intimately. One of her closest friends at the time was Belinda Carlisle, the frontwoman of The Go-Gos. Theresa and Belinda attended high school together and were roommates in college. While Belinda appears in hundreds of her photographs, and in many ways served as her muse, she’s never put on a pedestal.

Lobotomy interviewed Belinda, as well as Latino punk bands like The Bags and The Zeros. The zine’s pages documented punk’s free spirit and debauchery. As Theresa says, “The whole era was like a nonstop party.”

So whether Theresa was taking photographs of musicians in a bathtub or over chili fries at Tommy Burgers, the artists in the photographs are accessible and enjoying themselves. Instead of the usual seriousness ascribed to punk, Theresa’s photography captures the fun and hedonism that came with the times.

As Kereakes and Gehman curate the photographs and articles that comprise their book on Lobotomy, which will be released in the fall of this year, both are thinking of the legacy that Lobotomy has left behind, and how the zine documented a punk scene that is very different from today’s landscape.

Theresa says, “I had a boyfriend who once said, ‘I bet no one has ever told you no.’ And I said, ‘Actually, no, people tell me no all the time, and I think that’s unacceptable, so I just find my way to yes.’ I’ve got to get my way. And that’s what I think the whole punk rock scene was, people telling you no all the time.”

Can we play in this club? No. Fine, we won’t play in your club, we’ll just make one of our own. Will you play our music on the radio? No. Fine, we’ll have a guy in a record store play our music relentlessly. So we wouldn’t take no for an answer.”

“That’s what I think the whole punk rock scene was, people telling you no all the time.”

While resistance and rebellion are still fundamental pillars of punk, Kereakes believes that in today’s scene, many don’t realize that her generation “fought all the battles, and I don’t think they [the younger generation] knows that there were battles to be fought.”

Over punk’s 40-year history, the genre’s early days are often glamorized, or else they’re looked at academically, clinically, and anthropologically, when the people who lived through those days are still here, still a part of the scene, and are still making changes to it.

On her blog, Theresa describes the modern “punk renaissance,” and the distance between those studying it and those who actually experienced it. Theresa writes, “Maybe next they’ll start letting us teach students rather than have someone teach students about us.”

This year, Theresa Kereakes, Alice Bag, and Pleasant Gehman all spoke at a panel on punk at UCLA and directly answered student questions about LA’s punk scene. Whenever a question was “too academic,” Kereakes spoke about her own experience, to help students think outside of the scholarly mold. Each student could find her own voice, forge their own way, and like she and Pleasant did with Lobotomy, create their own movement.