The 18th Annual Latin Grammy nominees were announced on Tuesday morning, and the accolades piled on for fixtures in the industry. Take Residente, who holds a record 25 awards as half of Calle 13, or Shakira, who has the most Latin Grammys of any woman in history.

Reggaeton golden boy Maluma also snagged his fair share of nominations, which would seem to indicate that the Latin Academy of Recording Arts & Sciences is acknowledging more urbano sounds. But while pop-reggaeton got a few pats on the back, there was a clear omission: Trap en español artists were largely left out of the award hype, minus a nod for Bad Bunny, whose collaboration with J Balvin’s “Si Tu Novio Te Deja Sola” is a contender in the Best Urban Fusion/Performance category. J Álvarez’s Big Yauran is nominated for Best Urban Music Album, but that project is mostly boom bap hip-hop, with only a handful of trap en español tracks. The remaining nominees in the urban categories, like Kase.O’s El Círculo album or Residente’s self-titled debut, align more with older hip-hop sounds.

Trap’s exclusion from the nominations is significant, given how quickly the genre has swung toward the Spanish-speaking world and hypnotized listeners with its sludgy, Atlanta-bred beats over the past year. Bryant Myers, Anuel AA, Noriel, Fuego, Farruko, and Bad Bunny make up the tight core of trap powerhouses who have emerged from Puerto Rico, the Dominican Republic, and the U.S. to rack up millions of views on YouTube and Spotify. The trap wave has also extended into Spain and South America. Last year, Trap Capos: Season 1 became the first trap compilation to hit no. 1 on Billboard’s Latin Rhythm Albums, and Univision launched both radio programming and a new channel to keep up with demand for the genre.

But with some artists’ explicit lyrics and themes, trap en español may be a hard sell for both mainstream audiences and voting members of the Academy. Already, controversies and arrests surrounding artists have been a proven turn-off, and despite the genre’s popularity in certain regions, it’s still finding its footing across major Latin American markets. Trap might be too new, and as Leila Cobo, Billboard’s executive director of content and programming for Latin music, explains, not “everyone has quite wrapped their heads around it. A lot of people still don’t get trap. It’s not just the lyrics. It’s a different kind of sound and many purists don’t like it. Also, do remember people from all over the world vote for the nominees here; it’s not U.S. only. So, while trap is getting really big in many countries, it isn’t in others,” she tells Remezcla over email.

“A lot of people still don’t get trap. It’s a different kind of sound and many purists don’t like it.”

It’s an all-too-familiar story, one with echoes of reggaeton’s history as a diasporic genre born out of black, working-class struggle. Similarly, trap en español has faced difficulties breaking into radio, as it continues to be read as a street sound born in Puerto Rican barrios.

What’s more, the Academy isn’t exactly known for having a finger on the pulse of all things new and trendy; it’s faced controversy over the years for constantly handing awards over to industry titans. Even in its massive pop moment, reggaeton doesn’t usually fare well at the ceremony — a category for the genre didn’t exist until Best Rap/Hip-Hop Album was changed to Best Urban Music Album in 2004. Even with an urban category, critics have often wondered why reggaeton slights feel so frequent. When urban artists do end up with golden gramophones, it’s often for pop or radio-friendly collabs.

Because trap artists are still new to the game, it’s fair to say that they may not be familiar with the Latin Grammys’ submission guidelines. Nominations are chosen annually from 10,000 submissions across 48 categories entered between July 1, 2016 to May 31, 2017. They are selected by the Academy, whose membership information is confidential.

Remezcla reached out to representatives from the Latin Academy of Recording Arts & Sciences, who explained that because they are in the middle of voting, they could not comment on particular genres. They did share that their membership department visits several countries throughout the year to offer outreach programs to discuss the importance of becoming a member, and fosters new artists through the Latin Grammy Cultural Foundation.

Still, despite these efforts, young artists may face roadblocks to submission for consideration. According to the Latin Grammys website, the requirements to be a voting member in the Academy include a minimum of six song credits in the last five years, a figure that may be prohibitive for artists just starting their careers.

Trap artist Fuego got to the heart of the problem quickly: “Is there even an urban category in the Latin Grammys?” he joked in an email to Remezcla. Fuego says he did submit his 2016 album Fireboy Forever 2. Despite being an impressive – and early – example of the possibilities trap en español offers, the album didn’t make it through the selection process. According to him, in an often homogenous and image-obsessed music industry, the cards seem stacked against urbano artists, who are primarily artists of color. “You can count on one hand how many morenitos are in the Latin game, that are actually on radio and being nominated. I feel like they’re focused more on appearance than talent, and again, I’m talking about most award shows because honestly, I feel like the Grammys is the most real and prestigious award one can get.”

Still, he didn’t take his nomination snub too hard. (“I don’t feel an award will make me or break me,” he said.) His take was that trap was left out of this year’s Latin Grammy nominations largely because the quality of the music hasn’t evolved as quickly as its fan base.

“The quality of ‘Latin trap music,’ excluding my album Fireboy Forever 2, is not Grammy-worthy, none of it. You can ask anybody in the music business that knows. Don’t get me wrong; I like some of these songs that are out there. The artists will learn and it will get better.”

Trap is already entering a new phase: Cobo explains that major Latino entertainers are collaborating with trap artists more to reach younger listeners. The genre’s explicit content has softened a bit to cater to expanding audiences, but committed fans still give hardcore songs enough play on YouTube and Spotify. The growing enthusiasm could lead trap to have its moment at future Latin Grammy shows.

“You can count on one hand how many morenitos are in the Latin game.”

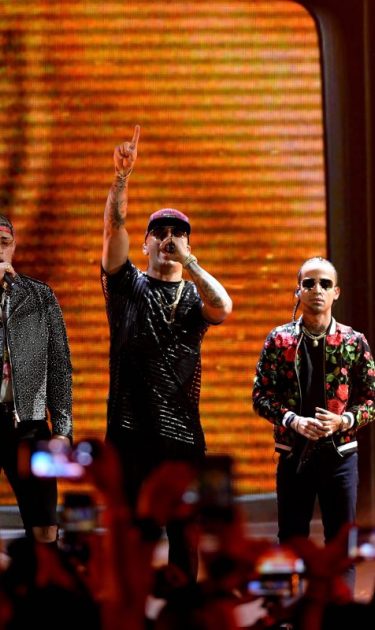

“You will definitely see trap represented. A bunch of trap acts performed at Billboard and Premios Juventud already,” she said.

Like lots of award shows, the Latin Grammys have a reputation for appearing old-fashioned, so it could be that they’re irrelevant to most trap artists, who measure their success through streams and concert attendance. One thing’s for sure: just like reggaeton, trap en español is worthy of professional critique and respect as much as other genres, and representation in the Latin Grammys is a good stepping stone to that.

Fuego isn’t closing the book on a future nomination, but is leaving it up to time. “One day,” he professed. “And if I never get one, I will still be the top dog.”