La Cisterna. As you enter through its main gate under a pair of fluttering Palestinian flags, the Cisterna municipal stadium looks like any run-down soccer field in the West Bank or the Jordan Valley. The parking lot is un-paved and the cars entering for the afternoon game send up yellow clouds of dust. The stadium itself is small and simple, an outdated concrete bowl that officially holds 12,000 people (though, according to statistics, rarely more than a couple thousand), most of whom sit on concrete bleachers that encircle the field. The concentric rows of stone bleachers even seem to conjure the ancient terraced slopes of Palestine, where for millennia farmers have sculpted the hillsides to cultivate olive trees and other sturdy crops in the dry Mediterranean climate. Here and there sprigs of grass inch through cracks in the dilapidated concrete and stone as a couple hundred of us settle in to brave two hours of scorching heat for the late afternoon match.

The team that calls Cisterna home takes the field in uniforms adorned with the Palestinian flag (and its colors of red, black, green and white) and a prominent gold map of historic Palestine emblazoned across the front of their jerseys. The players, for their part, look like your average Palestinians, as do the fans, some of whom are already taunting the opposing team’s players with witty asides and double entendres before the opening whistle. Cigarette smoke, a given at any Palestinian gathering, lingers over certain sections of the stands as vendors walk back and forth hawking Palestine-themed paraphernalia. Meanwhile, a group of five young kids plays soccer along the aisles, using an empty plastic bottle as their ball. At half-time Arabic music blares through a tinny PA system. Taking it all in, one could perhaps take some comfort in the fact that, despite the hardships of living under military occupation, it’s apparently still possible for Palestinians to find a modicum of normality, if only for 90 minutes of soccer.

But Cisterna municipal stadium is not in Nablus, Gaza, Jericho or Jerusalem, but in Santiago de Chile, roughly 8,000 miles away from Palestine/Israel. And the home team, Club Deportivo Palestino, is in the Chilean premiere league. The opposing team, Huachipato, hails from the Southern Coastal city of Talcahuano.

Palestino was established in 1920 by immigrants to Chile from what was then called Palestine (and was at that time under British rule). The team went professional in 1952 (check out this sweet team pic from that era) and today is as much a part of the Chilean soccer landscape as Colo-Colo, the premiere league powerhouse named after an indigenous Mapuche leader who famously resisted Spanish settler domination in the 16th century. But this fact does not make Palestino’s use of the classic symbols of Palestinian identity and nationalism any less striking, especially to the outside observer. This was certainly the case for me, a Palestinian raised in the U.S. In fact, going to Palestino games this past month marked the first time in my life I had rooted – live or otherwise- for a team repping the Palestinian flag. While excessive displays of nationalism generally rub me the wrong way, for Palestinians – like any stateless people – the flag is often more than just a flag. And seeing it plastered everywhere in a professional stadium felt pretty good; as if something that most people take for granted, something that was always taboo or impossible, was suddenly a reality. And yet I had travelled thousands of miles from New York City and even further from Palestine – almost to the bottom of the Americas – to experience such a moment. While in this South American country of 17 million people I set out to make some sense of the team knows as “Los Arabes”, and to find out more about the immigrant community from which it sprung.

Un cura, un policía y un palestino.

There is a saying in Chile that in every town you have a priest, a cop, and a Palestinian. As far as most such sayings go, it is not much of an exaggeration. Chile, according to most estimates, has the largest number of Palestinians outside the Arab world, with somewhere around half a million Chileans of Palestinian descent. The ancestors of today’s Palestinian Chileans mostly hailed from three villages in the vicinity of Jerusalem (Beit Jala, Beit Sahour and Bethlehem) and arrived sometime between 1900-1930. Those who made their way to Chile were predominantly Christian Palestinians (Greek Orthodox, Catholic, etc) fleeing war, famine or persecution, and/or simply seeking work or fortune in the West.

For over 400 years Palestine was part of the multi-ethnic Turkish Ottoman Empire. And until Turkish rule of the Levant was supplanted by British and French domination after World War I, Arab immigrants to the Americas arrived carrying Ottoman Passports. For this reason the newly arrived Arabs in Chile (a smaller number of whom came from what is today Lebanon and Syria) were for some time referred to as “Turcos” (Turks). Like most of the early Arab immigrants to the Americas (including North America), those arriving in Chile often worked first as peddlers or itinerant salespeople, plying their wares from door to door. And following the trajectory of so many other immigrants to the Americas, they moved up the proverbial ladder, eventually becoming owners of their own stores or small businesses in Santiago and in dozens of other cities and towns up and down the country.

The ancestors of today’s Palestinian Chileans mostly hailed from three villages in the vicinity of Jerusalem (Beit Jala, Beit Sahour and Bethlehem) and arrived sometime between 1900-1930.

The Santiago neighborhood of Patronato sits on the northern bank of the Mapocho River, an unimpressive mud-colored tributary that runs down from the peaks of the Andes Westwards to the Maipo River and then the Pacific Ocean, cutting through Chile’s capital city on its way. On the Southern side of the Mapocho lies downtown Santiago and what remains of its Colonial architecture, most of which has either succumbed to earthquakes or been swallowed by smog-stained buildings dating to the period of intense neoliberalization following the CIA-backed coup of 1973 and the subsequent 17 year-long military dictatorship (1973-1990) of strongman (and cape aficionado) Augusto Pinochet. Historically, the Mapocho marked the Northern border of Santiago, and during Colonial times it was on the North side of the river – and specifically in Patronato – that the indigenous and the poor were relegated, presumably only crossing the river to work for (or rebel against) the Spanish and then Chilean ruling classes.

Beginning around the turn of the 19th century, Patronato became the neighborhood where “los Turcos” – Chile’s Palestinian and other Arab newcomers – congregated and opened their modest businesses, transforming it in following decades into a commercial area full of immigrants. Today, Chile’s Palestinians are fully assimilated and are well-represented in business, arts, and politics. Most have moved out of Patronato and only a handful of visibly Arab businesses and restaurants remain, selling traditional Arab dishes, spices and trinkets. In the place of the departed Arab establishments can now be found a smattering of Korean shops and the overflow of Barrio Bella Vista, a once grimy but increasingly hip, tourist-friendly neighborhood that borders Patronato to the South-East. Although CD Palestino is one of the more visible and internationally recognized symbols of Chile’s Palestinian population, there are many other signifiers of upward mobility for Palestinian Chileans, ranging from a social club called “Club Palestino” (which is one of many ethnically-based country club-like spaces that every immigrant group in Chile seems to have), to a host of federations and foundations dedicated to Palestinian culture and politics.

Unlike Chileans of Italian, German, Spanish, or even Croatian descent, however, Palestinian Chileans are Arabs, and are therefore still subject, at least to some degree, to the Orientalist and Islamaphobic gaze endemic in the West. Furthermore, despite their success and assimilation, they are also associated with the diaspora of a stateless people (who are both loved and hated); a people still engaged in a politically-charged struggle for self-determination and liberation. Under these circumstances, then, blending in completely is not always possible. In the case of CD Palestino, however, standing out and embracing the markers of Palestinian-ness is central to the team’s identity.

Many of the Chilean Palestinian organizations, including those that are politically centrist or even right-leaning, take what would be considered in the U.S. to be relatively progressive or “radical” stands on Palestine. While this says more about the state of U.S. political discourse around Palestine-Israel than it does about Chilean Palestinians, it also speaks to the conscious decision on the part of Chilean Palestinians to associate with a diaspora which today numbers around six million people, most of whom are refugees or exiles descended from the 750,000 or so Palestinians driven out of their homes in 1947-‘48 when Israel was created at their expense. In other words, while many Chilean Palestinians trace their ancestors’ exodus from the Holy Land to before the 1948 Nakba, or “catastrophe, it has not prevented them from re-connecting with Palestine and its modern struggle for independence, often very publicly.

In this respect, soccer has played a pivotal role in the Chilean diaspora, both in reinforcing Palestinian identify and in articulating political solidarity. Over the years, for example, several Chilean professional soccer players of Palestinian stock have suited up for the Palestinian national soccer team (which has never placed higher than 84th in the world FIFA rankings) in its uphill quest to qualify for the world cup (the the 2006 film Goal Dreams tells the story beautifully). One of the Chilean footballers to have played for the Palestinian national side, Roberto “Tito” Bishara, played for CD Palestino until last year, while Reoberto Kettlun – who also played for Palestino between 2002-2005 – now plays on a Palestinian professional team in Jerusalem called Hilal Al Quds. While the Chilean players added international experience to a mostly inexperienced Palestinian team during qualifiers for the last two World Cups, their presence also highlighted the challenges of drawing a team from a dispersed population. It also drew attention to the obstacles faced by the Palestinian national team’s homegrown players, who, besides facing the daily nuisances and humiliations of occupation (restriction of movement, limited facilities, etc), have also been targeted by the Israeli military at alarming rates, with several players on the team killed, injured or imprisoned by Israel in recent years. While Chile is in many ways a frontier outpost in the Palestinian-Israeli conflict, Chilean Palestinians have closed the gap through sheer numbers, organizations, and soccer.

One recent controversy in particular made the proximity of the Palestinian-Israeli conflict apparent here in Chile, and Palestino was at the center of the storm. This past December, CD Palestino took the field wearing new jerseys. On them, the number “1” took the form of the map of historic (pre-1948) Palestine, a map which today encompasses Israel, the West Bank and Gaza. Almost immediately there was a firestorm, with the President of the Chilean club Ñublense, Patrick Kiblinsky Fried (an active member of Chile’s Jewish community) filing a complaint with the league. Chilean Jewish organizations jumped into the fray too, as did international organizations such as the Simon Wiesenthal Center, who claimed that the image of the map was “fomenting terroristic intent”. The governing body of the Chilean Premiere league bowed to the pressure and intervened, fining CD Palestino and ordering the team to discontinue the Jersey. Palestino obliged, kind of. They paid the fine and by the next game the jerseys had been changed. But the map did not disappear entirely from the uniforms. In fact it got bigger. Palestino was making it clear it would not be intimidated, but stopped short of an all-out confrontation with Zionists in Chile and beyond. Rather, in what seemed to be an effort to diffuse the situation while simultaneously sending a message to his fan base and the Palestinian community, Fernando Aguad, President of CD Palestino, was at once diplomatic and defiant. “I am the head of a sports organization, and I don’t involve myself in politics” Aguad said at the time. “First and foremost”, he continued, “ we are a Chilean team, but we cannot put aside our Palestinian origins…a new Jersey will be designed, taking every liberty to include the symbols and the territory of Palestine on it.” Aguad would stay true to his words. When the new uniform was unveiled at the next match, the map was now featured on the front of the jersey, in gold.

The controversy over the jerseys was reported on far beyond Chile’s borders, with mainstream media in the U.S., Europe, and IsraeI covering the story. Dave Zirin, sports historian and progressive columnist, weighed in with a whip-smart piece in the Nation in which he quoted a letter (that originally ran in Chile’s La Tercera) by Nicola Hadwa Shahwan, a former coach of the Palestinian national team and himself a Palestinian immigrant to Chile. Shahwan, not shying away from the political, writes:

“…Peace must be based on justice. If the Jewish community in Chile is interested in advocating for peace, then they could put pressure on the Israeli government to respect United Nations resolutions, to permit the Palestinian people to return to their homes from which they were expelled, and to stop persecuting anti-Zionist Jews who oppose the occupation. Sports, arts, culture and science are not oblivious to the reality of the people; on the contrary, they are the expression of their feelings and historical experiences. ..Club Deportivo Palestino interprets the most sensitive feelings of the Palestinians and all who raise the banner of justice, peace and freedom…. [I] call on sports fans to support this noble initiative.”

One result of the uproar, likely to the great displeasure of those who stirred it up to begin with, has been that the outlawed jersey is now more popular than it likely would have ever been, both in Chile and in the wider Palestinian and activist communities. (Personally, I have received orders from at least a dozen cousins and friends on several continents to bring them the jersey from Chile). In La Cisterna, the be-mapped jersey can no longer be seen on the field, but it is porliferating in the stands, and even the Palestino website is running pop-up ads promoting the sale of the banned jersey. The fierce Chilean rapper Anna Tijoux recently sported the jersey alongside visiting Palestinian-British rapper and songstress Shadia Mansour in a picture that circulated on Twitter. In other words, like many past attempts to erase, censor, or criminalize Palestinian historical memory or cultural expressions, this one failed, if not technically then certainly on an emotional and political level.

In talking to a wide range of people in Chile, however, I found that the most intriguing aspect of the jersey scandal has been the reaction of those without ethnic or religious connections to the conflict. Perhaps most stunning was the reaction within the Chilean premiere league. Shortly after the eruption of the controversy early in the new year, Palestino faced off against two of the most formidable teams with the largest fan bases in Chilean soccer, Colo-Colo and Universidad de Chile. During both of these matches the “Barra” or “hinchas” (hardcore fans) of Colo-Colo and U de Chile made public displays of solidarity with Palestino and the Palestinian people . Universidad de Chile’s home fans held up a banner with the Palestinian flag that read “Palestina Libre” (Free Palestine), while Colo-Colo supporters unfurled an enormous banner behind their goal which featured the Palestinian flag on one end, the Mapuche flag on the other, and the map of historic Palestine filling in for the letter “i” in the word “Resiste” (resist) printed in bold in the center.

I reached out to Kamal Cumsille, a researcher and professor at the Center for Arab Studies at the University of Chile in Santiago, to get his take on the reaction by other teams’ fans. “The support of the ColoColo and U de Chile fans was without a doubt important” he told me. “This whole controversy was really part of a larger dispute about how far Zionism is permitted to negate the historical existence of Palestinians. And the fans of ColoColo and U de Chile demonstrated that they are aware that this existence cannot be negated… And they took an ethical posture to make visible that existence which has been subject to attempts at erasure.”

Cumsille said he believed that despite some important similarities in the “structures of the problems [the two peoples] face”, not as many Chilean Palestinians would see the Palestinian and Mapuche struggles as the same. In spite of that, or perhaps because of it, the more I thought of the Colo-Colo sign in particular, the more it stuck me as an especially meaningful act of solidarity. The Mapuches, once the dominant indigenous peoples in what is today Chile, have a long history of dogged resistance to Spanish and Chilean conquest and rule, especially in the Southern half of the country. Even as we speak, Mapuche communities in Chile’s South are engaged in a political struggle over land and resources and subject to harsh government crackdowns, including, violence, intimidation and imprisonment. The parallels between the Indigenous resistance in the Americas and the Palestinians’ own struggle for human rights and against land theft and colonization (watch Oscar nominee Five Broken Cameras or Budrus to get a taste) are striking, but not often evoked on an international level. The similarities were clearly not lost on Colo-Colo’s fans. I soon found out that similar sentiments existed among Palestino fans, and especially among those fans with no direct family ties to Palestine.

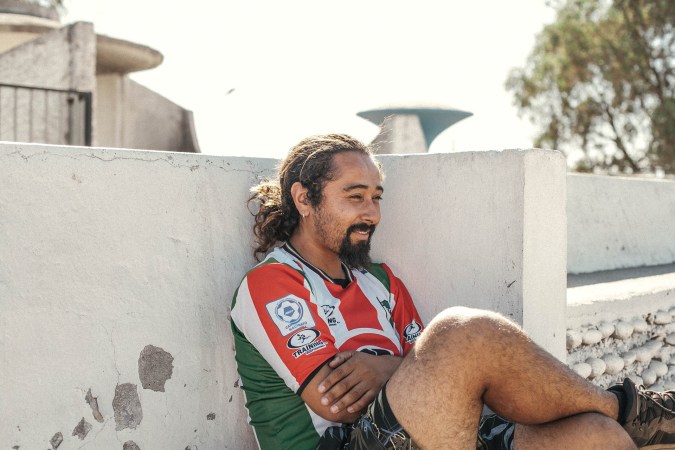

The day of the Huachipato-Palestino match at La Cisterna, I notice a young man with long hair and a Palestino jersey entering the stadium with his bicycle (yes, it’s that laid back). I approach him as he rests his bike against the concrete bleachers and we begin to speak. Suspicious at first of my dodgy Spanish, he warms to me once I tell him I am a Palestinian. I find out his name is Pedro Moraga. He is a history teacher, he tells me, but he has not had work for some years, so he does odd jobs and helps out with a show on a community radio station (called “Raices Poblaciones”) in his neighborhood in La Cisterna, the working class borough or “Communa” in which Palestino’s stadium is located. I ask Pedro about his support for Palestino and he is quick to clarify that he only comes to some of the games as he cannot afford to go to all of them, and that many of his family members are ColoColo fans. “Why do you support Palestino, then?” I ask him. Without missing a beat, Pedro tells me that for him it is an act of political solidarity. “I am not Palestinian but I feel close to them and support Palestino because I support Palestinian resistance and the struggle for autonomy and rights and culture. I am from an indigenous background and my family, we support Colo-Colo in my family, but Palestino too. For me supporting Palestino is 100% a political act.”

I ask Pedro if he sees a parallel between the Mapuche and Palestinian struggles for liberation.

“Yes, absolutely”, he says, “they have a lot in common. They are both fighting against systems that take their land and their rights. These are struggles against oppression and disappearance, resistance to economic power and against the minority that controls the majority. Palestino symbolizes that struggle.”

I thank Pedro and we exchange emails before we part ways. As I sit down two more fans enter our section and, using my built-in Palestinian radar, I can tell off the bat that they are of Palestinian extraction. In the U.S. and Europe I can spot a Palestinian in any setting at an accuracy rate of about %85. In Chile things get trickier, though, mostly because even your average non-Palestinian Chilean (with the typical mixes of Mediterranean and indigenous blood) often looks quite similar to your average Palestinian. Seeing as how I am at a Palestino game, however, I figure the numbers are on my side and I walk over and introduce myself to the two fans, both young women in their 20s. I greet them and tell them I am doing a story on Palestino. They seem unimpressed. I ask if they’re from Palestinian families. They nod, and without taking their eyes off of the action on the field they introduce themselves as Chadia and Javiera . “Have you visited Palestine?” I ask. Javiera points to her friend, again without looking away from the match. “She has, three times.” Chadia then takes the baton and starts by throwing out a couple sentences in Arabic. I respond with a couple formalities of my own. It’s a grammatically fucked up conversation. We both speak broken immigrant Arabic, only with different accents from opposite ends of the Americas. But there is still something comforting in the simple exchange, especially after weeks trying to tune my ear to Spanish. Chadia tells me she has spent time in Beit Jala and plans to go back soon, but insists that it is Javiera who is the hard core Palestino fan, and that she is responsible for bringing them both to the game. “I used to come with my father when I was a kid”, she says, “but for a while I didn’t come. Javiera is the crazy fan.” I look at Javiera, who raises her eyebrow and finally lets slip a smile, as if to say, “damn straight”.

“I like to come and hear people shouting”, she tells me. “It’s like a family. I feel proud and happy here.” I ask her about the jersey controversy. “[The jersey] wasn’t meant to cause problems” She says, “it was meant to have us all represented. They created chaos and an unnecessary fight over it…Stupidity. If we want to have our map we can, we are Palestinians.”

At that moment Palestino midfielder César Valenzuela scores to put Palestino ahead and end our interview. But for a moment, with the sun mercifully beginning its descent, we are all just Palestino fans celebrating a beautiful goal together.

Palestino hangs on to beat Huachipato 2-1 that evening and the fans go home happy. In fact, since the jersey controversy erupted earlier this year, Palestino has played pretty good football, and has managed to hang around at the top of the Chilean standings (they are currently ranked 4th out of the 18 teams in the 1st division). But regardless of their success this year or next, Club Deportivo Palestino is probably never going to become a truly global brand. After all, it is neither the most successful nor the most popular team in Chile. Its modest stadium is far from full, even on a good day. But there is no denying that Palestino, like the community from which it arose, is firmly rooted in Chilean society and the Chilean imagination. Similarly, Palestino is today a unique part of the Palestinian diaspora and the ongoing efforts by Palestinians – both under occupation and in exile – to keep their collective memory and identify alive in spite of almost a century of efforts to deny that such an identity even exists, let alone constitutes a people with rights to its land and property. In that sense, if we consider sport as culture – and soccer is most certainly a global culture – then the existence of Palestino can also be seen as a form of Palestinian cultural resistance. That it emanates from deep in the heart of the South American continent does not change this fact. On the contrary, it only highlights the team’s potential to deepen and diversify solidarity for Palestinians and for all people, everywhere, fighting for their dignity, freedom and self-determination. The Colo-Colo and Palestino fans who see a connection between the struggle of Chile’s indigenous peoples with that of Palestine’s half a world away are proof of this.

As the Israeli government and its supporters in the U.S. increase their PR and lobbying efforts to win over Latinos, it is not only the similarities between our various struggles against oppression that tie us together, but also the shared tactics and overlapping agendas of those in power. To find just one example of this we need not look any further than the increasingly militarized and surveilled U.S.-Mexican border. There, one of the many companies that will profit from the “border fence” and the accompanying “security” industry flourishing in its ever-expanding shadow along the Rio Grande is an Israeli company called Elbit Systems. It was Elbit’s expertise, I discovered, that brought us the “intrusion detection systems” outfitted on the apartheid wall (or “Separation Barrier”) that snakes through Palestine and is today taller and longer than the Berlin Wall. It makes sense, then, that Elbit would win the $145 million dollar contract from the U.S. government to install something called the “Integrated Fixed Tower” system along the Arizona-Mexico border. And there are plenty of other dots to connect in this Orwellian constellation where war is peace and pain and prejudice is profitable. Perhaps that is why, as I write this, I cannot help but replay again and again the words that Pedro Moraga spoke as we rapped in the sun-bleached stands at La Cisterna: “These are struggles against oppression and disappearance” he told me, “resistance to economic power and against the minority that controls the majority. Palestino symbolizes that struggle.”