Since the possibility of a Donald Trump presidency became more than a cable news running joke, and with ongoing police brutality and civil unrest serving as the background, politics have crossed over into the willfully apolitical world of sports. No longer content with “sticking to sports,” athletes have begun to use their platforms to shine the spotlight on social justice and activism. US-born Latinos have stepped into the conversation, particularly in the wake of Trump’s campaign and subsequent election.

Los Angeles Dodgers first baseman Adrían González is known for advocating for better treatment of his Latino brethren; not only did he petition MLB to allow accent marks on jerseys, but he also has boycotted Trump-owned or affiliated hotels, refusing to stay in them whenever the Dodgers are on the road. Meanwhile, in the NBA, Carmelo Anthony–whose father was a member of Puerto Rican anti-imperialism group the Young Lords –was, by all reports, the catalyst for last year’s emotional ESPYs message he relayed along with James, Chris Paul, and Dwayne Wade.

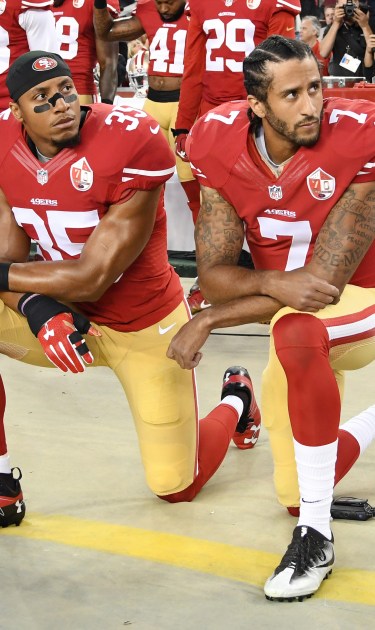

However, the main conversation that has thrown sports headfirst into a debate over whether politics should slither into the arena of competition has been that of national anthem protests. When Colin Kaepernick knelt for the national anthem on August 26, 2016, he began a chain reaction of protest, anti-protest, blackballing, and conversation that has exploded into full-on controversy. The then-San Francisco 49ers quarterback has become synonymous with shows of protest during the national anthem, but he is not alone; in fact, it appears that the number of athletes explicitly standing up against social injustice –or kneeling down, as it were – has only grown.

Just this week, a huddle of Cleveland Browns players knelt down during the anthem, removed from the line-up usually observed during the Star Spangled Banner. Those players join fellow outspoken activist-athletes like Seattle Seahawks’ defensive end Michael Bennett, Philadelphia Eagles players Malcolm Jenkins and his (white) teammate Chris Long, and NBA players like LeBron James, who criticized Donald Trump in the aftermath of Charlottesville earlier this month. (LeBron has not, however, participated in an anthem protest, but his vocal leadership has been invaluable.) Conspicuously, however, there has been a noticeable lack of Latino players–US-born or those who grew up in Latin America–protesting either the anthem or the current administration, which has made immigration one of its tentpole issues.

Why don’t more Latino players born in the United States speak up in the face of mounting racial tensions, anti-immigration legislation, and the generally white supremacist overtones of the last year in America? The answer is more complicated than it might seem.

One reason is that, unlike black players who were born in the United States, a vast majority of Latino athletes in the major leagues did not grow up in this country, nor do they live here during off-seasons. The effect of that reality is two-fold. First, those players have different racial norms that were molded by their own personal experiences in their own countries. That’s not to say that they can’t empathize or even rally for change in those arenas here in the United States; it’s more just a fact of circumstance that they have different experiences from players of color born in the US who might have come in contact with those issues first- or second-hand, and who have grown up in an era of escalating racial tensions and anti-POC and anti-immigrant legislation.

Second, Latin-American players–who make up the majority of the aforementioned percentages–aren’t anti-protest or activism; some just channel their energies towards their own home countries, rather than the United States, and that’s not something to fault them for. Take the Venezuelan collective of players in MLB, who have been repeatedly vocal about that country’s current situation. Due to the political turmoil, failing democratic process, and civil violence currently raging in Venezuela, one could forgive players like Pittsburgh Pirates catcher Francisco Cervelli or Detroit Tigers superstar Miguel Cabrera for turning their eyes back down to South America.

Similarly, Puerto Rico’s MLB group has been focused on the debt crisis raging on the Caribbean island, a debt crisis caused in part by American imperialism. Houston Astros shortstop Carlos Correa spoke about what a World Baseball Classic victory would have meant for Team Rubio and for the island, who at the time were rallying behind the team despite worries about bankruptcy and civil distress clouding La Isla del Encanto. It’s not a matter of solidarity that these players have not turned their actions towards the US; it’s more that their own countries are in need of athletes exhibiting leadership.

The more relevant reason for the lack of Latino protests, however, might be best explained by Baltimore Orioles outfielder Adam Jones, who spoke candidly last fall about the lack of anthem protests in baseball: “It’s a white man’s sport.” Despite baseball reaching its diversity peak this season (the league is made up of 32% Latino and Latin American players, and baseball has never had as many players of color as it does now, at 42.5%), Latino, Latin American, and black players are still out-numbered by white players in the major leagues. That it’s led to a mostly-white audience is no surprise, and with those conditions in play, it’s not surprising that peloteros feel no urge to publicly protest, despite baseball’s audience likely being the most in need of a wake up call.

And that’s just in baseball, where they make up a good chunk of the pie. Latino players are severely outnumbered in the NFL (under 2% last season, compared to 70% for black players), and if a Super Bowl-level black quarterback like Kaepernick can get blackballed by the league for his protest, what’s to stop them from simply replacing the handful of Latino players if they were to protest? Maybe there will be a change in the coming season, as this pre-season has seen more open displays of resistance than the entirety of the 2016 campaign, but that’s in the nebulous future, one that could see the administration devolve into more white supremacist/Nazi sympathizing.

In the meantime, the combination of the NFL’s clear hard stance against protests–despite its egregiously false claims that Kaepernick isn’t playing because he’s just not good enough–and its notoriously owner-friendly contracts will make it difficult for too many Latinos to join in on protests. At least, until a structural change makes that a less risky proposition…which is just how the owners want it. The NFL is the same league that just crowned a champion that features a quarterback who is a visible Trump supporter, a coach who congratulated 45 on his presidency, and an owner who is known to be friendly with the man in the White House, to the point where he recently presented Trump with a Super Bowl ring. That that owner holds a significant amount of power over the NFL (Robert Kraft is, along with the Mara family, the most influential owner in the league) makes it even more likely that it will continue to be an act of both rebellion and risk to protest the anthem. As if that weren’t enough factors against it, the NFL’s fanbase attributed anthem protests as the main reason for the decline in viewership last year.

So, with all that said, is it truly a surprise that US-born Latino players are staying (mostly) silent when it comes to protesting the anthem and the administration? Putting their jobs on the line for a country that they might feel doesn’t best represent them, and certainly a country that has a historical and systemic dislike for the other (read: non-white), feels like a proposition tilted heavily against them. Never mind that, for a number of Latin American players, their own countries need help just as much, if not more, as the United States. The next time you see Latino players lined up for the anthem, hands behind their backs, looking down, don’t blame them for not taking a stand; blame the country and the leagues that make it a losing battle to kneel in solidarity.