The year 2019 started with President Nicolás Maduro and opposition leader Juan Guaidó both claiming to be the official leaders of Venezuela. Over in Haiti, thousands of people were demanding the resignation of their president, Jovenel Moïse. As summer hit, a few hundred miles away in the Caribbean, former Puerto Rican Gov. Ricardo Rosselló was caught disparaging his citizenry in 889 pages of secret chats. Back in South America, Peruvian President Martín Vizcarra had dissolved Congress. By fall, Bolivian President Evo Morales was accused of voter fraud, Ecuadorian and Chilean leadership hiked prices on certain goods and services and Panama approved controversial constitutional reforms.

Suffice it to say, the people of Latin America and the Caribbean have had a tumultuous year – but with each crisis and scandal that developed, there were hundreds to thousands of people in each country and territory fighting back by crowding city streets and occupying state buildings.

As 2019 comes to a close, and many of our homelands continue engrossed in struggles against powerful regimes, we take a look back at what Latin American resistance looked like during a year that witnessed historic international uprisings.

Puerto Rico

The summer of 2019 will forever be an important time in Puerto Rico’s history. It’s the moment people-power toppled a corrupt and bigoted governor and reminded an archipelago still reeling from 2017’s devastating Hurricane María of its might. After 889 pages of damning chats between Gov. Ricardo Rosselló and his administration were leaked – revealing misogynistic, transphobic and homophobic conversations, as well as jokes about those who died from the Category 4 storm – Puerto Ricans were prompted to protest on July 13. A movement catapulted by secret chats became about so much more.

For some, it was the growing rates of violence against women or the unelected fiscal control board. For others, it was massive cuts to education and healthcare or the island’s colonial status. But for the nearly million people who shut down highways, closed up shops, took down U.S. flags and created revolutionary art in Old San Juan and across the Caribbean archipelago, it was about removing pro-statehood Rosselló from La Fortaleza, the governor’s mansion, which the massive demonstrations accomplished when he stepped down on August 2, 2019. The historic moment energized Puerto Ricans, who continue to push back against Gov. Wanda Vázquez Garced and fight for a free and just Puerto Rico.

Chile

On October 17, high school students in Santiago, Chile’s capital, rallied against fare hikes by refusing to pay for public transportation and encouraging others in their country to do the same. The fare-dodging demonstration turned into social disobedience when some students forced station gates open and cracked fires, sparking, whether they knew it or not, one of the biggest protest movements in Latin America this year.

In the nearly two months since then, Chile has risen against social inequality, with hundreds of thousands of people throughout the South American country taking to the streets and using art to protest neoliberal policies that have made the country one of the wealthiest in the region but that hasn’t changed the stark economic disparities that lingers on.

While the momentous demonstrations have forced the government to make changes, including President Sebastián Piñera reversing the fare hike and introducing a new spending package and constitution, the state’s brutal response to the protests have kept people demonstrating, many now against police abuse. According to Reuters, at least 26 people have died and 13,000 others have been injured in cases related to the protests. Recently, the name of Gustavo Gatica, a 22-year-old student who was blinded after he was hit with police rubber bullets while photographing the rallies, has become a rallying cry against state violence in Chile.

Panama

Last month, protests erupted in Panama against constitutional reforms that had been preliminarily approved by the legislature. Hundreds of protesters in the Central American country flooded streets in Panama City and attempted to enter the National Assembly, demanding public input and expressing their anger over several constitutional reforms. Among them: amending the constitution to define marriage as between a man and a woman, the creation of a constitutional court that gives more power to congress by allowing them to pass a national budget, set their own salaries and oversee investigations of judges and prosecutors, as well as privatizing higher education and more.

During the protests, which started on October 30 and carried into November, there were multiple reports of excessive force, including the use of tear gas, as well as incidents where politicians made homophobic remarks at demonstrators. At least 40 people were arrested.

Bolivia

In August, hundreds of Bolivians took to the streets to protest then-President Evo Morales’ re-election bid. The politician, who became the South American country’s first Indigenous leader in 2006, had been in power for 13 years. While widely commended for his leadership, including shepherding the country’s growth, paving roads, sending the first satellite to space, curbing inflation and increasing rights and opportunities for Indigenous communities, protesters – including some supporters – grew concerned that he had been in office for too long.

The demonstrations mushroomed last month, when Morales claimed a victory in the presidential election and was accused of voter fraud, allegations that multiplied after a report from the Organization of American States (OAS) found “serious irregularities” concerning the vote count. The mass protests, which had then turned violent, and calls from military leaders for Morales to step down forced him to resign as president in what he and his supporters have called a coup.

Since then, the country has become socially and politically divided. As Morales has accepted political asylum in Mexico and opposition leader Jeanine Áñez has declared herself interim president, she and her supporters have attempted to undo some of Morales’ changes, including turning the country from a secular state that respected all religions into a Catholic one and, more controversially, removing the Wiphala flag, an emblem of the Indigenous people of the Andes region that was made a national symbol in 2009, from state uniforms and buildings. The protests, which have turned into a battle between Morales supporters and the opposition, have become increasingly violent, with a death toll of 26 and abuse accusations by the Human Rights Watch against Áñez’s government.

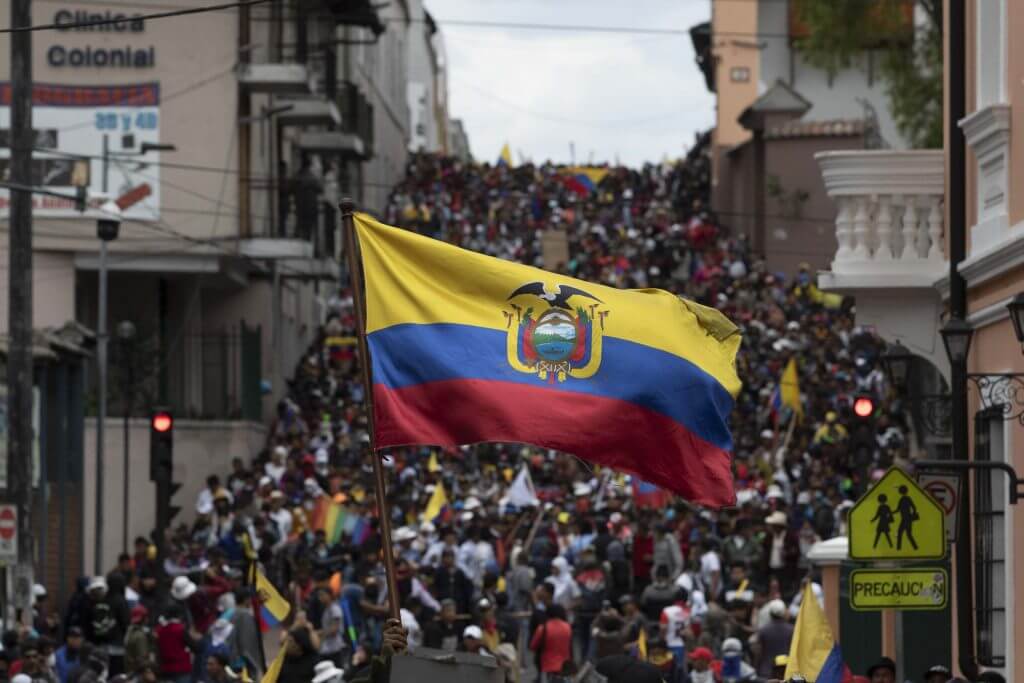

Ecuador

On October 1, President Lenín Moreno announced that his administration would end fuel subsidies as part of a package of economic measures with the International Monetary Fund (IMF). The cut, which took place two days later, resulted in the doubling of diesel fuel prices and a 30% hike in regular fuel. From there, the cost of basic goods skyrocketed. On October 3, unions, student groups and Confederation of Indigenous Nationalities of Ecuador (CONAIE), a collective of various Indigenous groups, joined forces to organize a protest. Thousands of Ecuadorians flooded the streets of Quito, the South American country’s capital, calling for a decision reversal. Many taxi, bus and truck drivers also joined the demonstrations, blocking roadways. To disperse crowds, military and authorities excessively fired tear gas and tanks. The following day, Moreno declared a state of emergency.

By October 8, protesters, many of them Indigenous individuals, had overrun Quito, forcing the president to relocate his government to the coastal city of Guayaquil. Demonstrators also occupied at least three oil fields and main roads, essentially forcing the country into a standstill. The following day, protesters briefly took over the National Assembly before they were forced out by police with tear gas. It was neither the first nor the last violent clash between strikers and the state. With demonstrators refusing to stop resisting, Moreno organized a conversation between his government and CONAIE. The dialogue, which was televised, led to collaborative new economic measures to tackle overspending and debt without economically burdening the people. After repeatedly saying he wouldn’t reverse his decision, Moreno ultimately withdrew the IMF-backed plan, bringing fuel costs back down and ending the two-weeks long uprising.

Haiti

Since the start of the year, Haitians have been protesting around the Caribbean country, demanding the resignation of President Jovenel Moïse. While demonstrations for his removal started in the summer of 2018, a response to a hike in fuel prices, the movement intensified this February, with activists and everyday Haitians calling for a new government, political autonomy, social programs and the prosecution of corrupt officials. While the months-long uprising aims to topple Moïse, it’s also confronting neoliberal policies that have kept the country poor and its people scouring for basic goods. They are demanding public policies that invest in social programs, an end to foreign dependence and interference, food sovereignty, environmental protections, reparations, new economic models and more.

According to the United Nations, there have been 42 deaths and 68 injuries related to the protests since mid-September.

Peru

This summer, massive changes occurred in Peru, sparking protests across the South American country. In September, Peruvian President Martín Vizcarra dissolved congress, a move he hoped would end a yearlong fight with rightwing lawmakers, who held a majority in the chamber, over his corruption reforms. Under Peru’s constitution, presidents are allowed to dissolve Congress and call for new elections if members show no confidence in a government.

According to opinion polls, most Peruvians support the president’s decision. That’s why it came with little surprise when, following the dissolution, protesters gathered outside of Congress in Lima, the country’s capital, to pressure lawmakers to step down.

More recently, protests occurred again last week when Peru’s Constitutional Tribunal released opposition leader Keiko Fujimori from prison. The politician, who is the daughter of former authoritarian President Alberto Fujimori – who is currently imprisoned for corruption and human rights crimes – was jailed for a year for allegedly receiving illegal contributions to her campaign and money laundering, claims she denies. Following the news, hundreds of protesters gathered on the streets denouncing her release.

Nicaragua

In 2018, massive nationwide protests in Nicaragua made international headlines, but while media attention on the unrest in the Central American country has dulled, the same can’t be said about turmoil in the country. Throughout the year, Nicaraguans have continued to protest and demand the resignation of President Daniel Ortega, despite his government banning opposition demonstrations.

There have been multiple marches calling for a “halt to repression and the murder of farmers.” There have been large-scale vigils for those who died by state force during protests, including teenager Matt Romero who was killed last year. And there have been hunger strikes calling for the release of 130 political prisoners who were incarcerated due to their involvement in the years-long demonstrations.

As of February 11, 2019, there were at least 568 deaths related to the crisis, the non-governmental Nicaraguan Association for Human Rights (ANPDH) reports. Of them, 248 were youth and 235 were adults. Just last month, the United Nations called on the Nicaraguan government to end its “persistent repression of dissent.”

Colombia

In Colombia, the South American country is currently experiencing one of the largest mass demonstrations in recent years. It started on November 21, when hundreds of thousands of people participated in a strike to protest increasing unemployment and economic reforms under socially conservative President Iván Duque. Since his inauguration in August 2018, his administration has faced criticism for economic stagnation as well as his handling of the peace process with Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias de Colombia (FARC) rebels and the rising attacks on Indigenous groups as they fight illegal mining.

While the ongoing protests have mostly been peaceful, law enforcement have deployed tear gas at demonstrators in the country’s capital of Bogotá, ordered a curfew in Cali and closed borders to block entry by land and sea from Ecuador, Peru, Brazil and Venezuela. Last week, Colombian teenager Dilan Cruz died from wounds sustained by riot police who were forcefully breaking up demonstrators. The 18-year-old, who was getting ready to graduate from high school that week, participated in the protests to call for greater access to higher education. While demonstrations carry on – and given new energy with Cruz’s passing – Duque has met with unions and business leaders who organized the initial strike.

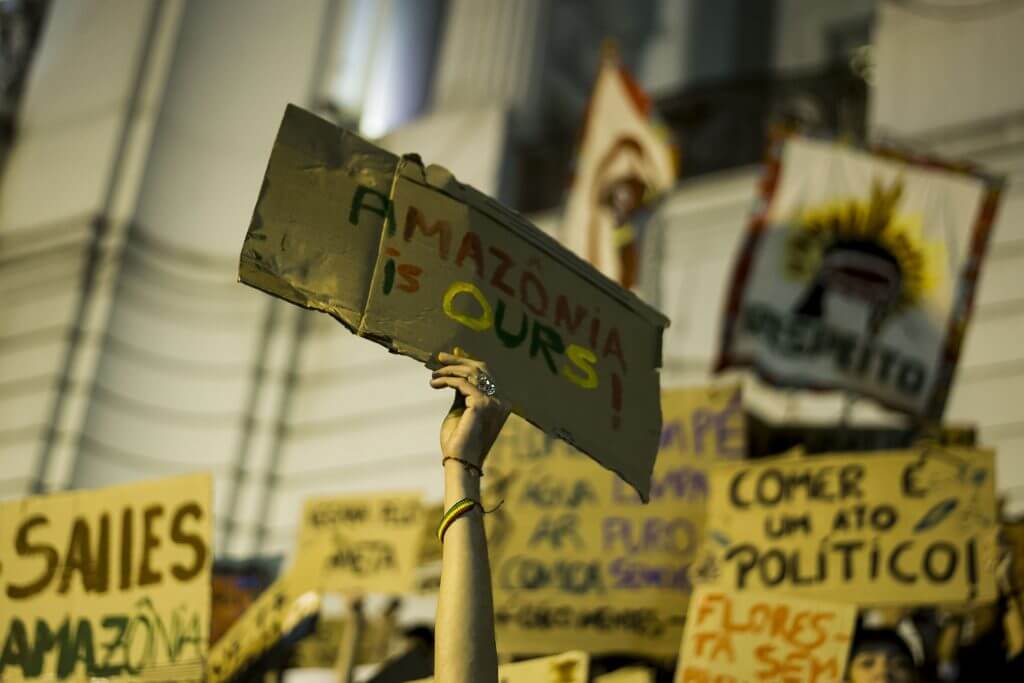

Brazil

In August, thousands of Brazilians crowded streets across the South American country in response to the worsening Amazon fires. In Rio de Janeiro, thousands flooded the steps of town hall, lambasting President Jair Bolsonaro’s plans to develop the Amazon forest and allow mining and commercial agriculture on protected Indigenous reserves. In São Paulo, demonstrators blocked a main avenue while calling for the resignation of environment minister Ricardo Salles. Even in Florida, Boston and cities worldwide, the people rallied at Brazil’s embassies to express outrage over the president’s failure to protect the Amazon.

According to data released by the National Institute for Space Research last month, the rate of deforestation in Brazil’s Amazon has spiked to its highest level in 11 years. For many, Bolsonaro is partly responsible due to his history of denying the severity of the deforestation, dismantling several of the country’s environmental protections, rejecting foreign aid to help fight fires and the increase in assaults and invasions of Indigenous land in the country since he took office on January 1, 2019.

Venezuela

In January, Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro had his second inauguration, an event that has sparked on-and-off protests in the country throughout the year. To start, his second presidential inauguration was met by opposition leader Juan Guaidó, the president of the National Assembly of Venezuela, declaring himself acting Venezuelan president on January 23, a controversial claim that was recognized by almost 60 governments worldwide and sparked a crisis concerning who is the legitimate president of Venezuela.

Since then, Guaidó has led a series of rallies. The largest one came on April 6 when tens of thousands of the politician’s supporters participated in what was called Operation Freedom to oust Maduro from power. What was thought to be the start of an uprising, however, dwindled down over the last few months, with Guaidó’s own support dropping from 60% in February to 42% in November. Recently, he has attempted to take advantage of the revolutionary energy sweeping South America by holding the biggest anti-government demonstration in the country in the latter half of the year last month. Inspired by the protests that toppled Morales in Bolivia, which Maduro has described as a coup, Guaidó has called for daily protests.