When Indigenous peoples from all over the world meet in Washington, DC, on January 18, 2019, they’ll send one clear and united message to President Donald Trump: They will not tolerate the injustices affecting their communities.

At the Indigenous Peoples March, defenders of human and environmental rights will gather in the nation’s capital – one day before the Women’s March – to bring attention to issues of voter suppression, the ways that walls and borders have negative effects on families, sex and human trafficking, police and military brutality, and what advocates refer to as an “environmental holocaust” that greatly impacts Indigenous peoples. This marks first time since the 1970s that a march of this scale will take place, and various Indigenous communities – ranging from groups in Puerto Rico to South America and Central America to the United States – will participate.

“I think it’s a collective cry for help because we’re in a time of crisis that we have not seen in a very long time,” says Nathalie Farfan, an Ecuadorian Indigenous woman and event organizer. “When I say crisis, I mean collective crisis. A lot of Indigenous people from around the world are suffering from the same colonization.”

That colonization has exhibited itself in many ways, including by attempting to erase language, cultures, and traditions of these groups. It has also inadvertently resulted in generations of Indigenous peoples growing up assimilating to mainstream Eurocentric notions of beauty – to the point that their own self-identity was compromised. In Farfan’s case, she had a nose job at 21 to make her appear less Indigenous and more Spaniard.

She can’t reverse her nose job, but she can ensure future generations of Indigenous women realize their power and beauty within.

“We’ve been colonized so much and in so many different ways, whether by the Spaniards or the Brits, so the European colonization is what’s really divided so many Indigenous people,” Farfan tells me.

But many are fighting back against the norms imposed on them – instead they embrace their own cultures, histories, and physical characteristics while they fight for human dignity and conserve the environment. Farfan attributes this sentiment partially to Trump and his administration, whose policies she believes are destructive to Indigenous communities and environmental rights.

“This is the time to bring awareness to these injustices that have divided us all,” Farfan says. “That’s why we are saying unity is power, and we need all Indigenous people to come.”

She is part of the Indigenous Peoples Movement, a grassroots collective that includes numerous tribes, organizations, associations, societies, individuals and businesses, including Standing Rock Sioux Tribe, Schaghticoke First Nations, United Native Americans, Friends of Kuntanawa Nation and many more.

Farfan says the march will result in pushing for policy that supports human and environmental rights and voting people into office who honor those rights. And though these communities remain underrepresented in politics, ground has been made with the election of Indigenous women (or those with Indigenous ancestry), including Debra Haaland, Sharice Davids, and Ruth Buffalo.

Fellow organizer Cliff Matias, a Native American Taíno/Kichwa performing artist, educator, and photographer, says the march conveys the message that the people are actively trying to find solutions to problems that the president’s administration is ignoring.

“A march of this magnitude in DC is going to really keep the momentum going (of events such as Standing Rock) even more so than just the fact that it’s large, but in the amount of attention we’ve gotten so far,” Matias says.

And, of course, the environment is a reason many have decided to join in. For Heritier Lumumba – a former Australian football player born in Rio de Janeiro with Indigenous roots in the Congo and Brazil – protecting the environment is close to his heart because of his heritage. He has helped recruit people from all over the world to take part in the march.

He says the march serves to eliminate any existing borders among Indigenous people and helping them send a clear and united message for the first time in the digital age, pointing to the Black Lives Matter movement as an example of its potential.

——

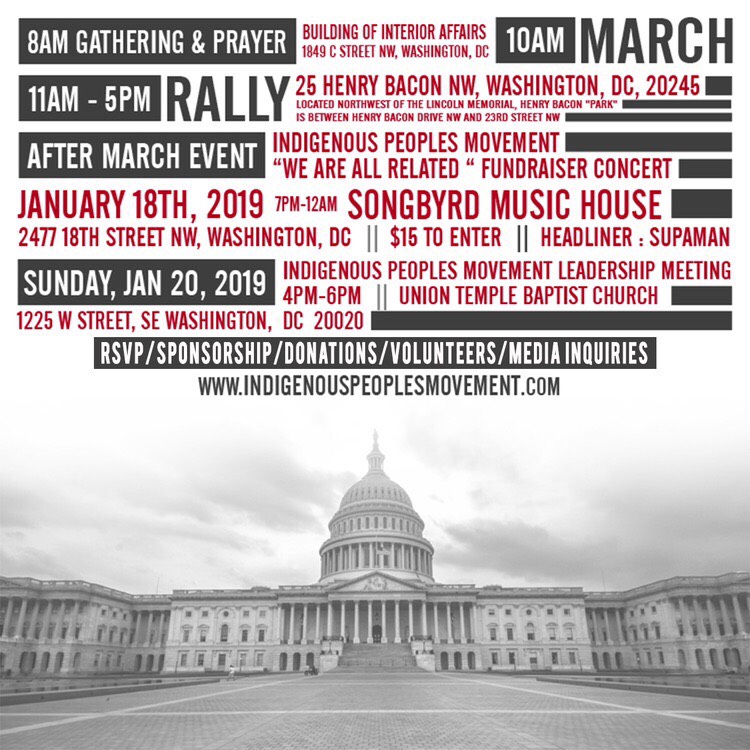

The Indigenous Peoples March, dubbed #IPMDC19 on social media, is expected to bring about 5,000 people, and begins at 8 a.m. for prayer at the Building of Interior Affairs in Washington, D.C. The march and all-day rally follow at 9 a.m. and 10 a.m., respectively. A fundraising concert featuring various international Indigenous artists and acts at Songbyrd Music House is scheduled from 7 p.m. to midnight. Visit the Indigenous Peoples Movement website for more information.