Soccer fans are known for keeping grudges, but fans all across Latin America are taking their schadenfreude at Chile’s absence from the World Cup to a whole new level. Even now, a week after the start of the tournament, the memes and jokes about the Chilean team and its most famous players continue to appear on social media.

How could a team that exhibited an exciting attacking game in Brazil four years ago spark such antipathy from Mexico to Argentina? The answer lies in the way players, managers and the media handled their newfound success.

In 2007, soccer visionary Marcelo Bielsa took a Chilean team that had been demolished at the Copa America and rebuilt it in his image. Over the next three years, Chile became a hard-pressing, relentless attacking machine that didn’t give its rivals a minute to breathe. But the biggest change was psychological. Bielsa convinced the team that they were capable of facing any team in the world on their own terms, with no fear.

Fans and experts all over the world fell in love with this new Chile, and though they were eliminated in the round of 16 of the 2010 and 2014 World Cups, the team left a great impression. Although Bielsa left at the end of 2010, players like Arturo Vidal, Alexis Sanchez and Claudio Bravo continued their progress and signed multi-million dollar contracts with some of the best teams in Europe, becoming celebrities at home.

Like the nouveau riche of soccer, Chile forgot it was once poor, and started disrespecting its neighbors and rivals.

Chile completed its transformation into a top tier team at the Copa America they organized in 2015. But the tournament also marked the turning point from admiration to disdain. A week into the competition, Arturo Vidal crashed his Ferrari against another vehicle in the outskirts of Santiago, as he and his wife were returning from a casino. Vidal, who suffered minor injuries, was under the influence of alcohol. Despite breaking the law, he wasn’t disciplined and merely lost his driving license. The episode left the sensation among fans and pundits that players felt above the law.

They weren’t behaving on the field either. In the quarterfinal against Uruguay, with the game tied, Chilean center-back Gonzalo Jara stuck his middle finger in Edison Cavani’s backside during an argument. The Uruguayan striker slapped Jara in retaliation. The referee only saw the last part of the spat and sent Cavani off. Chile took advantage of the superiority in numbers and won the game 1-0. Uruguayans never forgot to the offense, or the fact that many tried to justify it.

Chile won the tournament, for the first time in its history, defeating Argentina in penalties, and repeated the feat the next year in a special centennial edition of the cup. But like the nouveau riche of soccer, it forgot it was poor once, and started gloating and disrespecting its neighbors and rivals.

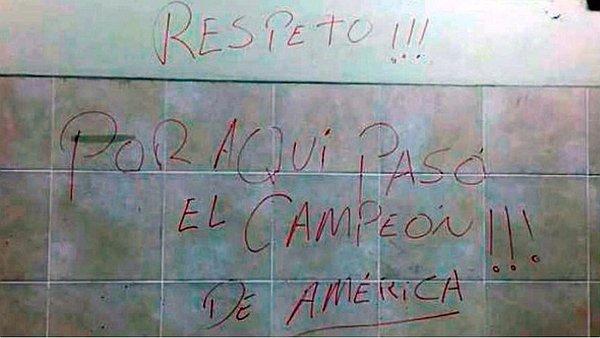

First, Claudio Bravo and Chile’s national team manager, Felipe Correa, scribbled the phrase “Respect, the Champions of America passed through here” on the locker room walls of the the National Stadium of Lima, after winning a World Cup qualifier against Peru. The image of the defaced wall went viral and sparked outrage across the continent.

Chilean players added fuel to the fire by reminding everyone at every turn how good they were. “It’s the best (national team) in the world. It’s the one that plays the best. Doesn’t matter the rival, we always play the same,” said Arturo Vidal during a press conference in August of 2016.

Fans didn’t help either. With seven infractions, Chile topped the FIFA ranking of sanctions for disrespectful behavior from home fans, ahead of Mexico’s five. The offenses included homophobic, racist and xenophobic chants against rival fans and players.

If that wasn’t enough, Chile provided its detractors with fresh material when they complained that Bolivia fielded an ineligible player during their 0-0 tie in Santiago and in their 2-0 victory in La Paz against Peru. The tribunals ruled in favor of Chile and, per FIFA regulations, changed the result of both games to a 3-0 against Bolivia. This boosted Chile in the standings and further soured already tense relations between the two neighbors. Fans in the rest of South America criticized the ruling, arguing that Chile was winning in court what they couldn’t win on the field.

With three qualifying games left, Chile and Bolivia met again, this time in La Paz. Chile needed a win to secure their spot in the World Cup, while Bolivia was already eliminated. Vidal, again, stirred the pot before the game when he said that “Bolivia watches the World Cup on TV.” The already furious Bolivians took the game as a matter of national honor and defeated Chile 1-0.

On the last match day, Chile arrived with a slim, but realistic chance to qualify. However, they lost against Brazil 3-0, and Peru and Colombia tied 1-1 in Lima, giving Peru the last spot in South America. Ironically, the complaint that gave Chile the points against Bolivia also gave 3 points to Peru, which ultimately made the difference between the two. That fact wasn’t lost on fans all over the continent.

The schadenfreude flowed all over the Internet in the form of memes, WhatsApp messages and brilliant video mashups and animated parodies. Even more so when a Chilean lawyer attempted to sue for a supposed collusion between Peru and Colombia to maintain their tie. His case wasn’t accepted by FIFA for lack of grounds to investigate.

The night of the elimination, Chilean journalist Juan Cristobal Guarello reflected on their recent past and had harsh words for his countrymen: “We’re the most hated national team in South America,” he said in a video that went viral. “Imagine how bad it was that the Uruguayans preferred Chile to be eliminated than Argentina. In the end everyone wanted us to lose. Sure, because we defeated them, but also because we dedicated ourselves to boasting about how good we were,” he said.

As the months passed, the Chile jokes reappeared every time there was a World Cup-related story. At the draw, during the craze of the Panini album and the arrival of the teams to Russia. But perhaps the most telling demonstration of the animosity happened last week in Moscow. Brazilian and Argentinian fans, the most bitter of rivals in South America, who constantly make fun of each other, put their differences aside for a moment to sing together “And where is Chile?”

La Roja faces a long road if they want to return to the World Cup, and a longer one if they want to regain the respect and admiration of the rest of Latin America.