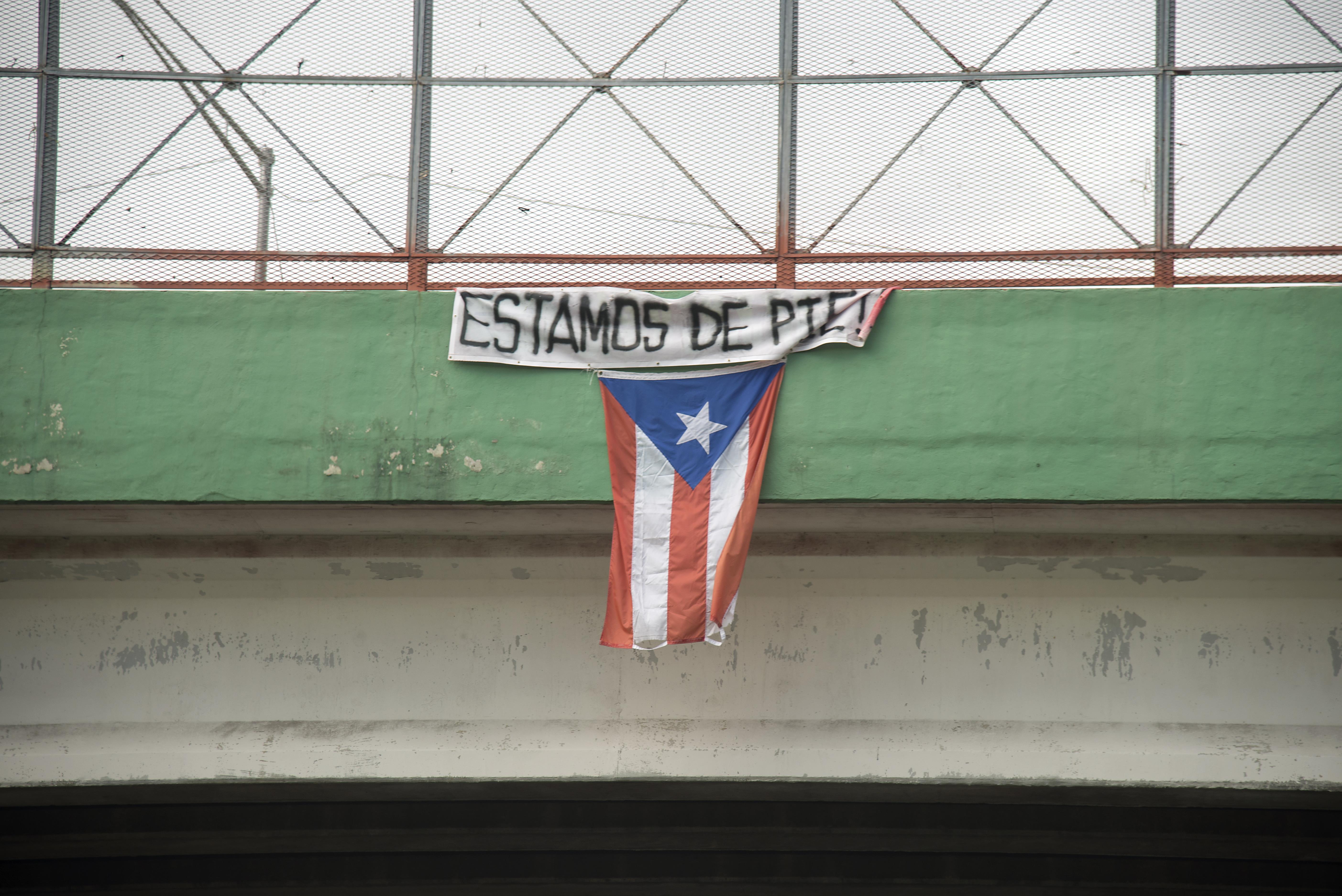

Blackouts remain so frequent in Puerto Rico today – nearly six months after Hurricane María – that a state of disaster preparedness feels like a norm that may never change. Re-establishing routines after a natural disaster is a key factor in coping with trauma. But in this instability, normalcy seems impossible, and the mental health of residents on the island is already suffering as a result.

The Department of Health in Puerto Rico has reported a 246 percent increase to calls about suicide attempts at Línea PAS, the national suicide hotline; from November to January, the agency received 3,050 calls of this nature. (The hotline reported 1,075 of those calls came in January alone.) The number of suicides has increased, too: 253 people committed suicide in 2017, a 29 percent increase from the year prior. About 38 percent of those cases occurred from September through December, after María.

But the mental health community hasn’t necessarily seen an increase in requests for preventative treatment, according to Dr. Karen Martínez González, a psychiatrist and director at the University of Puerto Rico’s Center for Study and Treatment of Fear and Anxiety. Taking steps to avoid that degree of crisis, she says, isn’t a priority for some people—because their lives are likely still too shaky to even factor in the state of their mental health.

“It could be that people are still in the process of getting basic necessities. There are still people without electricity in their homes, there are still people who haven’t been able to return to work,” she tells me. “So that instability, when you don’t have your basic necessities, you’re not going to be thinking about your mental health and how to better your mental health. I need to know how I’m going to bring food home, how I’m going to feed my children.”

Last Thursday, a system failure caused a widespread outage in San Juan and at least 15 other municipalities on the eastern side of the island. An explosion at a major substation mid-February left the metro dark while the west coast endured scattered power loss as a result of another issue with the electrical grid. The Puerto Rican power company warned of selective blackouts due to a lack of funding – something some residents believe has already begun. Either way, continued repairs and sudden failures keep the blackouts coming.

And let’s not forget, of course, the lingering 12 percent of the island that’s yet to have electricity restored. Some municipalities, like the north-central town of Morovis, have gone without the public utility for six months. Doubts surrounding the accuracy of the power authority’s reported statistics have perpetually circulated. Many people believe the numbers are misleading, that more people in Puerto Rico are without power than are represented.

Dr. Martínez says the mental health community expected a spike in cases of post-traumatic stress disorder and other anxiety-related consequences. They knew suicides and suicide attempts would likely increase, too: “We saw it after Katrina in New Orleans, we saw it after Sandy in New York,” she says. But the storm has left many clinics shuttered, and doctors have left the island, leaving patients unsure about where to get care.

After a decade-long recession, nearly 44 percent of the population is considered by CDC standards to be living in poverty; about half of the island relies on the public health system for medical care. But the doctors who accept government insurance cannot necessarily treat anxiety-related disorders effectively, González says.

“A lot of times they’ll evaluate you with a case manager or a social worker, or someone that isn’t necessarily clinically prepared to provide treatment…” she says. “They tell you you have an appointment every three months with a psychologist, or every four or five months with a psychiatrist, and we know that that’s not effective, especially not for symptoms that occur after a traumatic event like a natural disaster.”

The program Martínez directs, CETMA (its acronym in Spanish), specializes in anxiety. The approximately 15 medical students there work with evidence-based therapies that, especially in the beginning, are intensive. While the effectiveness of treatment helps the turnover of patients to flow, their bandwidth caps at about 45 active patients at once. And because a San Juan hospital houses the center, denizens hailing from other areas of the island cannot commit to the necessarily high frequency of appointments.

There is another community-serving program like this, although not strictly concentrated in anxiety, in southern town of Ponce at the Ponce Health Sciences University. For Martínez, however, a restructuring of mental health treatment within the public healthcare system is absolutely necessary. In August, CETMA began a project to to identify barriers for providers and educate them in evidence-based therapies; halted because of the storm, it’s only recently picked back up. They’re also working to implement the same quality of services in Puerto Rico’s schools, and may be collaborating with community organizations for additional guidance in identifying needs.

While CETMA operates within the University of Puerto Rico budget, there are organizations that offer specialized care – nonprofits like CoNCRA, the Puerto Rico Community Network for Clinical Research on AIDS, which offers mental health services for the HIV positive community, and the Alianza Para Paz Social (ALAPÁS), where crime victims and people who coping with the loss of loved ones can participate in group therapy — that do accept donations.

But in treating the trauma inflicted by Hurricane María and the subsequent, continued crisis, what would be most beneficial, Martínez says, is more licensed professionals. “When we’re talking about mental health, really what we need is the manpower. It’s the people that can directly provide these services to people,” she says.

Rough estimates report between 100,000 and 300,000 Puerto Ricans have already relocated out of the island, which can negatively affect economic recovery – further fueling the exodus.

Like the constant blackouts that continue to trigger anxiety in survivors of the storm, the state of Puerto Rico feels like a perpetual cycle of decline, like a machine with so many broken parts to fix. But it is possible. For immediate repair, we need to prioritize the lack of access to quality mental healthcare. Read on to learn how you can help or get help.

Donate to Alianza Para Paz Social (ALAPÁS)

Started to commemorate the life of Laura Isabel Aponte Rivera, a 19-year-old killed at a club, ALAPÁS offers services to those affected by crime. Donate here.

Donate to Puerto Rico Community Network for Clinical Research on AIDS (CoNCRA)

CoNCRA offers assistance, including mental health assistance, to those with HIV and AIDS. Donate here.

Support the Congressional Hispanic Caucus

Support the Congressional Hispanic Caucus and all individual congresspeople who continue to fight for relief and a just recovery for Puerto Rico.

Donate to the Maria Fund

Donate to Maria Fund, where 100 percent of monies raised support grassroots community initiatives impacting immediate relief needs and working toward long-term recovery goals.

Línea PAS

Call Línea PAS at 1-800-981-0023 for help in an emergency crisis. The 24-hour hotline can also provide guidance and references to mental health services to anyone, at any time.

CoNCRA

To learn more about services at PR CoNCRA, see its website, call 787-753-9443, or email info@PRCoNCRA.net.

Centro de Estudio y Tratamiento de Miedo y Ansiedad

To contact el Centro de Estudio y Tratamiento de Miedo y Ansiedad, call 787-758-2525 (extension 3431) or email cetma.rcm@upr.edu.

Ponce Health Sciences University

For information about services at the Ponce Health Sciences University, call 787-812-2525 or 787-812-2543 from Monday to Friday between 7 a.m. and 4 p.m.

ALAPÁS

Contact Alianza Para Paz Social (ALAPÁS) for information on group therapy for victims of crime, or those coping with the loss of a loved one.