The extraordinary mass mobilizations following the killing of George Floyd, have made Latinos of all races ask themselves how they can step up to support the Black Lives Matter movement and the fight against racial violence and white supremacy entrenched in the American power structure.

Images of thousands of protesters taking to the streets with tumult and passion over the last month are reminiscent of the Civil Rights Movement of the ‘60s, and a lot can be learned from one particular moment in 1964.

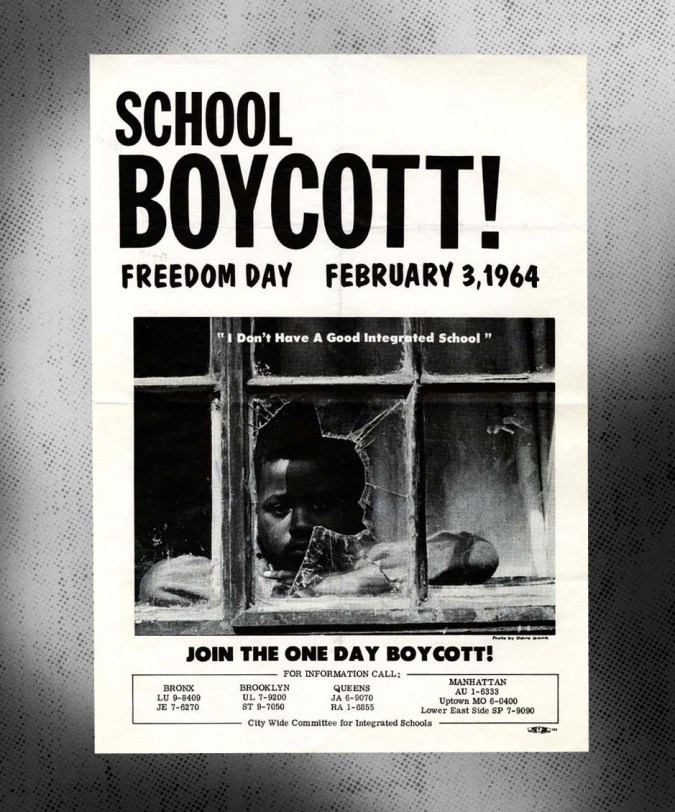

It all came to a head when Black and Latinx leaders came together that year. The groups planned a boycott of New York City’s public schools in response to racism and segregation in the city’s education system, which was—and still is—one of the most segregated in the country. The school boycott became one of the largest demonstrations of the Civil Rights Movement, yet is an event many have not heard of.

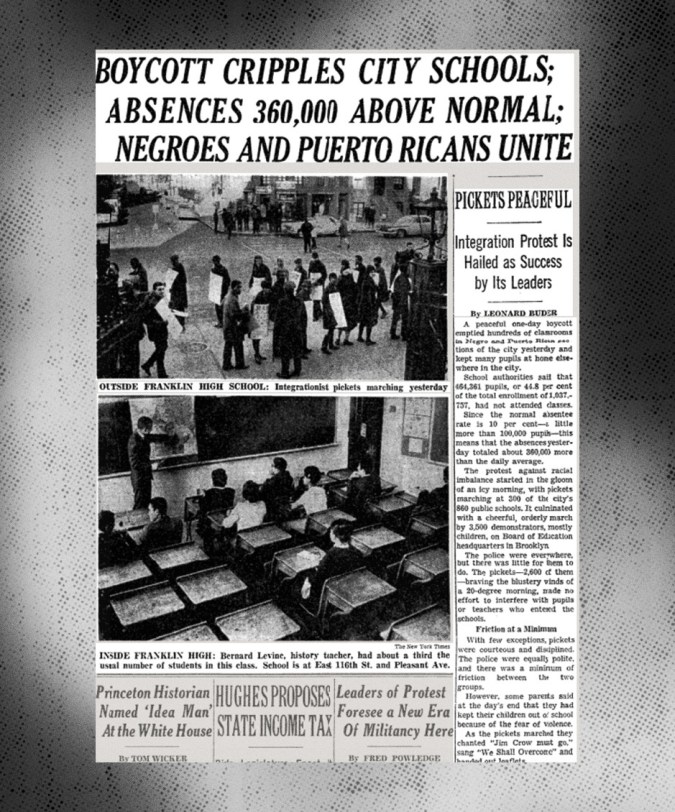

In the winter of 1964, six months after the March on Washington, 460,000 Black and Latinx students, families and activists participated in the boycott and protests. At the time, schools that enrolled students of color had inferior facilities, fewer school supplies, less experienced teachers and extreme overcrowding. So much so that they operated in shifts and the school day only lasted four hours for students.

Black and Latinx activists argued that test scores in the city were worse than in places in the Deep South under Jim Crow laws.

The best kind of education for an American child is a racially balanced education.

“Nobody can do these children more harm than these children are being done every day in this public school system,” said Reverend Milton Galamison, one of the organizers of the boycott from Bed-Stuy, Brooklyn, to ABC the day of the boycott.

Galamison was a Civil Rights leader who, along with March on Washington organizer Bayard Rustin, directed much of the New York City school boycott.

The demonstration gathered the support from intersectional groups and organizations in the five Boroughs—including mothers of students of color, the Black Panther Party and Latinx groups like the Young Lords. Most of the Latinx students and parents who took to the streets were Puerto Rican and carried signs in Spanish in the large crowds.

“We memorized chants like ‘Jim Crow must go!’ and some of the Black [non-Latinx] kids even tried to learn the chants in Spanish some of our moms were shouting,” P.S. 92 graduate Mariana Ortiz says. Ortiz participated in the boycott when she was 13 years old.

The Ortiz’s were one of the first Puerto Rican families to move into Corona, Queens, which at the time was a predominantly Black neighborhood. Malcolm X and Langston Hughes lived nearby and the Black Panthers had their main printing houses there, where most of their newspapers and printed media came out of.

“My father got involved with some Panthers because he was a mechanic and would fix cars around the neighborhood, he also started going to meetings downtown to help other Puerto Ricans get involved.”

Ortiz’s father eventually joined the Young Lords, a civil rights organization from the ‘60s whose members fought for the empowerment and self-determination of Puerto Rico, Latinxs, and colonized people. The organization is famous for adopting some of the organizing tactics the Black Panthers used, which included demands for a radical change to the segregation and inequality in the education system in American cities.

Segregation had been illegal in New York City schools since 1920, according to Board of Education reports, but housing discrimination helped to maintain a racially segregated and Segregation was also preserved by the school board, at the behest of white parents, by gerrymandering attendance zones.

The nearly 500,000-people protest was received with great backlash and repression where many activists and parents were arrested. The New York Times Editorial Board called students a bunch of scofflaws and truants who were skipping school by adult sanction. And a lot of the white opponents got very angry. They felt like the Black and Puerto Rican communities were pushing too hard and getting out of control.

In response, white families, and especially white mothers, staged a counter-protest a few days later to shamelessly advocate in favor of segregation. The New York City public schools, however, responded by implementing a very small and limited busing program for integration between 30 white schools and 30 Black and Latinx schools.

For Ortiz, that meant she could attend a mostly white school in Jackson Heights, Queens.

Today, schools in NYC continue to be among the most segregated in the country and parents and students in Corona, Queens often protest underfunding and overcrowding. Although the neighborhood’s demographics have changed—going from majority Black in the ‘60s to predominantly Latinx in the last two decades—the struggle remains the same.

Acknowledging a common struggle as continuous and interrelated can expand both communities’ sense of belonging and power.

“I remember a Black lady who sometimes handed out fried bologna sandwiches on our way to school for free. She was there on the street the day of the boycott… she was doing her part, too,” Ortiz recounts in 2017. The retired hairdresser passed away in 2018 at age 68.

The fight for racial justice needs to have multi-racial solidarity to avoid being isolated and silenced. That’s why forging real unity through protests, concrete campaigns and movements can be effective. The Black Lives Matter movement needs wide support—including other people of color, Latinxs of all races, and white people—in order to force concessions from the power structure, which benefits from the status quo.

For Latinxs, it also means confronting anti-Blackness in the community and unlearning white supremacist attitudes as a result of the legacy of colonization and colorism in Latin America, while learning about activism and coalition-building from the past. If education and racial justice galvanized both communities and brought them together in 1964, it can happen again today in defense of Black lives and liberation.

“I believe and will always believe that the best kind of education for an American child is a racially balanced education where people of different ethnic groups are learning together,” Reverend Milton Galamison told WNYC after the largest protest of the Civil Rights Movement in that cold winter in 1964.

Luis Gallo was an artist-in-residence at the Queens Museum in 2017 where he researched Black and Latinx solidarity, grassroots activism and hidden histories in NYC.