Shortly after the sun rose on April 10th, about a week and a half before Easter, Emiliano Zapata was already awake and riding his horse. He rode along the cool countryside with the comfort that comes from knowing the land. The obvious and hidden trails, the creeks, the hills, he knew them all. Zapata had both hunted and hid in that land.

Years before, when he fought for Francisco I. Madero—who eventually disappointed him—this land was among the first places Zapata had seized control of in his beloved home state of Morelos. Together, he, Madero and several others wanted to overthrow the government. The plan, Zapata thought, would be to redistribute the land. Most revolutions die without accomplishing much. It’s why the successful ones become ingrained in a nation’s psyche. Almost inevitably, they become romanticized and referenced by those whose politics are far removed from the revolutionary.

The Mexican Revolution lived—at least in as far as it overthrew and replaced a government. And so, remarkably, the first goal lasted long enough to make the failure of the second goal hurt men like Zapata that much more. As the leader of the campesinos saw it, Madero had betrayed the cause. Madero was killed—betrayed—but lived long enough to hear Zapata call him a traitor. Zapata lived and, as a master horseman, continued to ride like he did that spring morning in 1919.

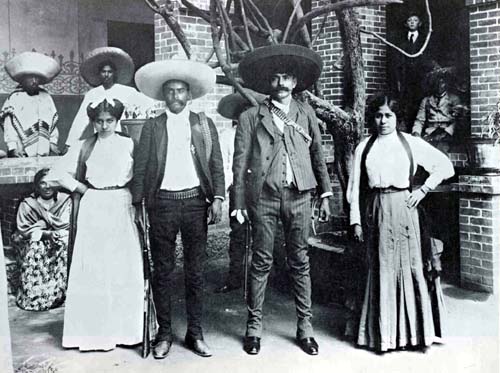

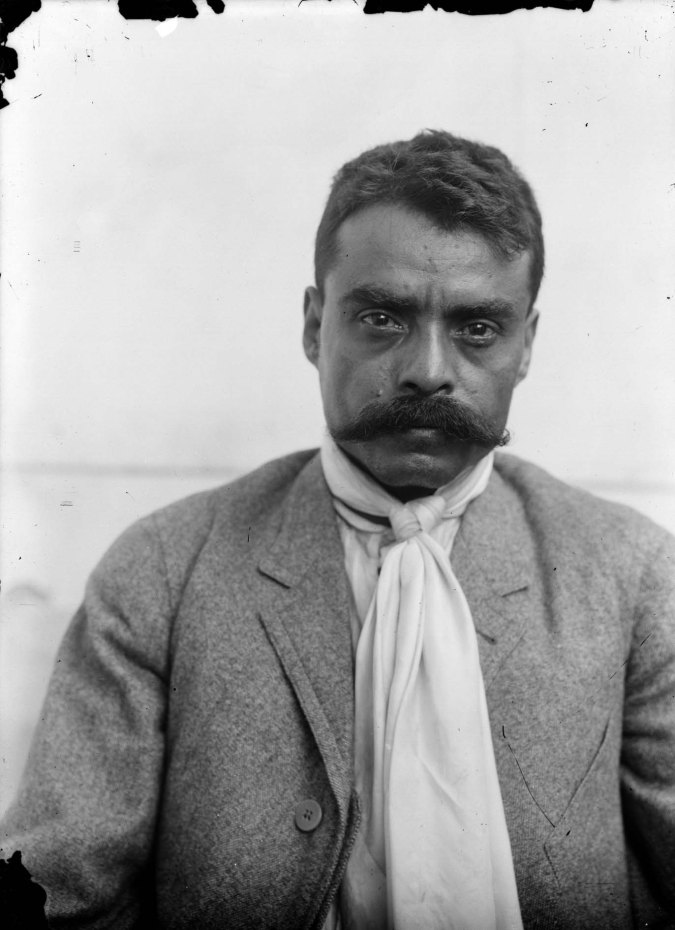

Known as a dapper man, one can easily imagine Zapata riding on that cool morning, his mustache immaculately groomed, wearing his usual dark-colored, three-piece suit. A neckerchief tied loosely around his neck, a large sombrero shading not just his eyes but part of his face, all of it smelling like it had been out in the sun and dirt for too long. He rode and breathed the fresh countryside air and pondered. There had already been several attempts on his life. As with Madero, it wasn’t uncommon for the highest of leaders to die at the hands of treacherous men. And yet, it was that same betrayal brought Zapata to this idyllic place that morning. He’d grown desperate.

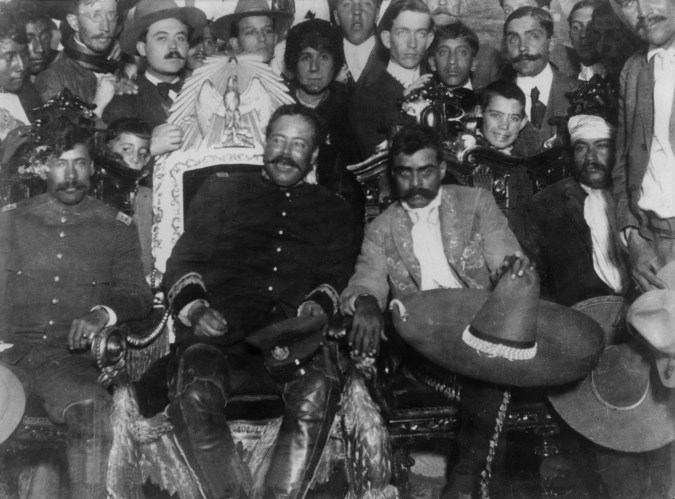

Years before that morning, Zapata and Pancho Villa—leader of the northern revolt—sat side-by-side in the presidential chair in the country’s capital. They posed for a picture. Villa smiled, his grand mustache not large enough to hide his jovial eyes and smile. Zapata sat to Villa’s left. He gave a stoic, almost menacing stare into the camera. If you were among the poor, this picture captures what was arguably the high point of the revolution. If you were among the elite, the picture concerned you, even if only symbolically.

But since that day, the fortunes of both Villa and Zapata—the revolution’s most charismatic figures—had turned. Villa lost several key battles, twice in Celaya, and eventually retreated to the Sierra Madre mountains, where he hid from the US forces intent on capturing and killing him for raiding their country. Similarly, Zapata and his men fought to survive. This, among other reasons, was why he reached out to Jesús Guajardo, a constitutionalist. Years before, Guajardo had presided over the killing of hundreds of unarmed Zapatistas. But now, he claimed he was ready to fight for Zapata.

Their first contact was the type that happens in love and war. A few weeks prior to that morning, Guajardo had received an order to once again attack Zapatistas. But instead of following orders, Guajardo was discovered by a superior a few hours later in a cantina, presumably drunk. He was jailed before he was ultimately allowed back in the field, and Zapatista spies said Guajardo felt hurt and disgruntled by the scandal. It became the perfect moment for Zapata to smuggle a note to Guajardo.

Like teenagers in an illicit love, they wrote and snuck messages to each other. Zapata asked Guajardo to join his side. Guajardo agreed. Eventually, they met and as a sign of good faith Guajardo killed fifty-nine of his own men. He also brought the one thing all those in revolt consistently want for: weapons and ammunitions. Still, Zapata was wary.

As the day became hotter, Zapata continued to ride. He’d been fighting for the better part of a decade. In Anenecuilco—his home, some twenty kilometers north of the Hacienda de Chinameca he was riding outside of—his family had fought for far longer. During the War of Independence, Zapata’s grandfather was one of the boys who snuck across Spanish lines and delivered whatever insurgents needed in their fight for liberation; tortillas, gunpowder, liquor, salt. Later, Zapata’s uncles fought in the War of Reform. They also fought against the French Intervention. On both his maternal and paternal sides, locals associated Zapata’s family with courage. The type of people who wouldn’t betray your trust. A century of fighting and now, potentially, the future of Zapata’s fight, and by extension the fight of his people, rested on this meeting’s outcome.

He waited. While waiting he heard reports federal troops were near. Zapata and his men investigated. They found nothing. He waited longer. He waited so long, in fact, that Guajardo sent a formal invite from inside the house hosting their meeting. Zapata, not yet ready, declined. When Guajardo sent Zapata a beer—to combat the escalating heat—he again declined. Perhaps it was a poisoned drink, Zapata thought. Perhaps, as some of his spies suspected, this was all a ruse.

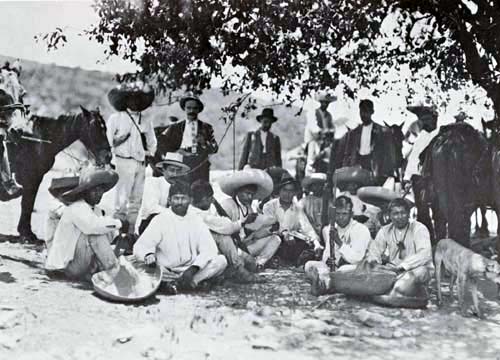

Finally, hours since dawn, in the early afternoon—2:10pm to be exact—Zapata decided to meet. He told ten of his men to follow. The rest stayed behind and rested, trying to stay cool under the shade of the surrounding trees. The house they would meet in was inside the hacienda gates. He and his ten men rode inside. They approached the house, and as they did Guajardo’s soldier saluted Zapata – a man who until that moment, he’d considered his enemy. It’s quite possible it was the first time most of these men had seen Zapata in the flesh.

There he was: Emiliano Zapata. The man who’d long been the enemy of the federal government. The man who Mexico City newspapers called a bandit, a terrorist, a barbarian whose savagery inspired comparisons to Attila. Emiliano Zapata, who had not just inspired fear but also a devotion so intense his followers would rather die than turn against him. Emiliano Zapata. They wrote songs about him. They praised him. If you’d seen him then, you might even think he was immortal. Emiliano Zapata. This is who they saluted.

They raised their rifles in the air and shot at the sky. And as Zapata and his men rode closer, the entire thing looked something like preparations for a parade. Zapata dismounted. The show of respect continued with a bugle sounding three times.

Once. Twice. The third bugle’s note still hung in the air when those who had just paid their respects lowered their rifles, aimed and shot Zapata. And though not all of them hit their target, nearly a thousand men inside that hacienda fired their guns.

The local hero died, betrayed on his own land, never fully knowing some of his notes to Guajardo got intercepted. The correspondence ended up in the hands of the same general that had caught Guajardo in the cantina. And during a supper, a few weeks before the day of Zapata died, that general—González—showed the notes to Guajardo. He accused him of being not just a drunk but worse: a traitor. Stunned and eventually in tears, Guajardo understood how treasonous acts end. He knew he’d get executed. But Gonzalez said he could spare his life. And so, Guajardo, with no options, agreed to ambush Zapata. If successful, he’d live – so long as Zapata was either captured or killed. Morelos’ favorite son died.

“Our general Zapata fell, never to rise again,” said a Zapata aide of one of the Mexican Revolution’s ultimate betrayals. In that gunfire and chaos, Zapata’s horse suffered a wound and rode away, scared and alone. Guajardo’s men kept Zapata’s lifeless body. They loaded it on a mule and traveled some twenty-five kilometers north to Cuautla. Inside a police station, authorities identified Zapata’s remains. They took photographs and the following day, newspapers across the country wrote of Zapata’s death.

Locally, in Cuautla, before his burial, thousands came to view the body. Some saw it and knew—despite the swelling—that it was Zapata. They cried like babies, even the grown men hardened by war. “The wings of our hearts fell,” one Zapatista said after seeing the body.

Others saw the same body and refused to believe it was him. As he lay there, lifeless, looking so vulnerable, they refused to believe it. And so, Zapata lived on in the types of stories and songs told to Mexican children, that then get passed on for generations. Tales originally told by people who swore they were true.

They say Zapata never died that April 10th. That he lived and fled to the Arabian Peninsula and would return when most needed. They said something about his dead body wasn’t right. That a scar was different, that a mole was missing, that the body had all ten fingers, when the real Zapata was missing a finger.

“We all laughed when we saw the cadaver,” one of Zapata’s soldiers said decades later. “We elbowed each other because the jefe was smarter than the government.” They say Zapata knew about Guajardo’s impending trick and that Jesús Delgado — a spitting image of Zapata, who traveled with the general as a body double —was the man killed. Others say it was another man, Agustín Cortés, or Joaquín Cortés, or Jesús Capistrán, or, as Zapata’s son put it, “some pendejo…from Tepoztlán.” Whoever it was, the name didn’t even matter. The important thing was that, according to these stories, Zapata lived and would eventually return.

And some say he did return. They claimed he’d visit only when protected under the cover of night. Others swore that, just like on the dawn of April 10, 1919, they’d see him atop his horse. He’d ride up in the mountains and always keep watch. Others said they saw that same horse, alone, galloping in the hills. They said it was an impossible white color.

Several decades after his murder, the daughter of a man appointed by Zapata to protect the land documents that proved their ownership, spoke of Zapata’s return. She said Zapata was an old man by then, and too aged to continue his struggle.

Zapata, whether you see his picture as a young man or were among those who claimed to have seen him in old age, has come to symbolize whatever noble cause the Mexican Revolution stood for. It was that same cause that for years brought together veteran Zapatistas. Increasingly, they too became old. And each year, on a day like today—April 10th—they gathered and expected Zapata’s return. A resurrection. He’d arrive and together they’d continue fighting for justice.

Today, a century after Zapata’s death, across Mexico and other parts of the world, the living—and perhaps even the dead—continue their fight inspired by Emiliano Zapata.