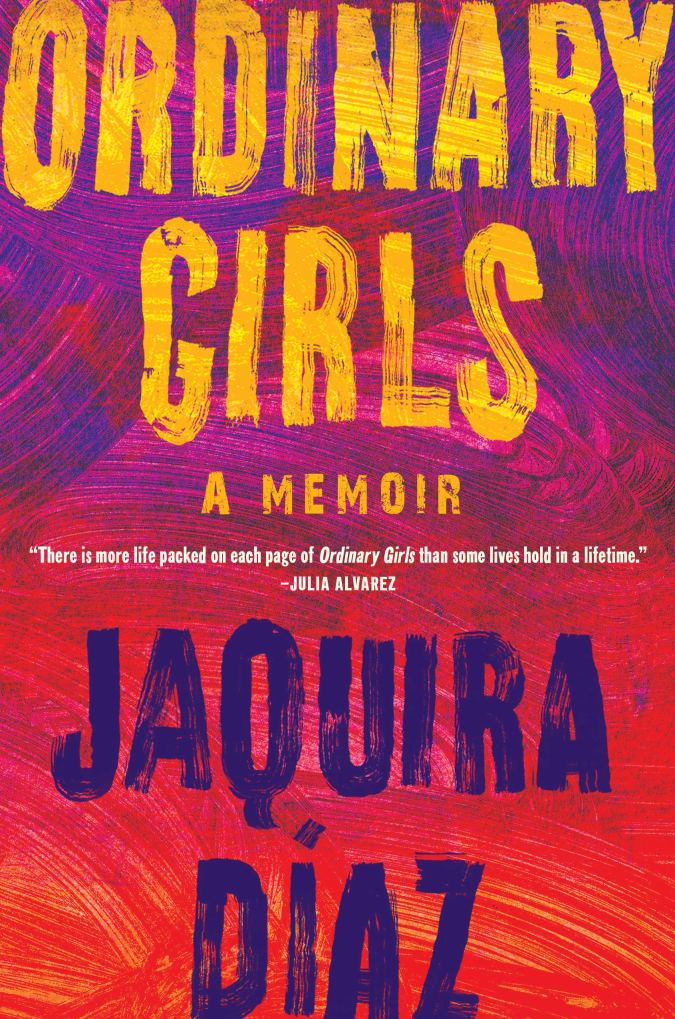

In Jaquira Díaz’s debut memoir Ordinary Girls, sisterhoods are forged by fire — from abusive relatives to predatory men to street violence. These girls often find no recourse, except in each other.

“I didn’t know it yet, none of us did, but it would be these hood girls, these ordinary girls, who would save me,” the author writes in the widely anticipated text that was published last month through Algonquin Books.

“It would be these hood girls, these ordinary girls, who would save me.”

Ordinary Girls follows Díaz from girlhood in Puerto Rico to her formative years in Miami Beach and what happens when she attempts to forge her own path. In her coming-of-age years, Díaz deals with her mother’s addiction and schizophrenia, her brother’s violence, her fraught relationship with her father and her grandmother’s racism. As she grapples with her own substance abuse and suicide attempts, she must also contend with the trauma of sexual assault.

Amid honest and searing vignettes of her life, Díaz also weaves in Puerto Rican history and the headline-making crimes that stayed with her (among them is the death of 3-year-old Lazaro Figueroa, whose mother, Ana Maria Cardona, Díaz writes letters to).

While memoirs are traditionally written to find healing through looking back at difficult circumstances, the intimacy and charged emotion that Díaz imbues in her book make it far from cathartic.

However, one important motivation kept Díaz going during the writing process: the need to see more stories like her own. In the final essay, which shares its title with the book, Díaz writes: “This is who I write about and who I write for … For the girls who never saw themselves in books. For the girls who love other girls, sometimes in secret. For the girls who believe in monsters.”

Remezcla caught up with Díaz to talk about Ordinary Girls, what it means to be a Latina writer in today’s publishing world and what she’s working on next.

We have edited and condensed this interview for clarity.

I read that you worked on this book for more than a decade and that it started as a collection of essays but then turned into a memoir. What changed in terms of how you wanted to tell the story?

“It took me sitting down and becoming physically ill in order to get the work done.”

I started writing a novel. I did that for a few months and then I had to stop because it didn’t feel true, even though I didn’t change the things that happened in my life. It felt like I was lying because I wasn’t being my authentic self. I was paying more attention to the plot of the story. I had to stop to take a break and go back to writing it as nonfiction. I needed to refocus and think about the larger story — what I was trying to say, how I was trying to connect my personal story to a larger world and what I was trying to say about girlhood, about Puerto Rico, about growing up in the diaspora, about growing up in poverty, about living with mental illness and with a parent who suffered from mental illness and addiction. I needed time to think about the larger stories right, that thing that I was trying to get the reader to focus on, rather than a plot and rather than just a personal narrative.

Writing about so many difficult issues from your past, how did you try to practice self-care during this process?

I wrote four other books while I was writing this one. That felt like catharsis, writing a novel that felt like play, like I was inventing a completely different world. But writing nonfiction was not at all cathartic. It was serious work. It took me sitting down and becoming physically ill in order to get the work done.

Self-care sometimes meant going to therapy, sometimes meant changing my diet, trying to get sleep, taking time off from work altogether, from writing and working a day job — just so that I could save some money so that I could pay bills, so that I could get my life back on track. It took exercise and a combination of a number of things, but it always felt to me like being well was out of reach. It always felt like self-care was just a process that would take a lifetime in order to get to a point where I was OK again. Still today, even after I finished writing the book, it’s still a process that’s ongoing.

In terms of going through that struggle, you’ve also talked about how growing up you didn’t see your own life story reflected in a lot of books and that you wanted to create that. What have been some memorable reactions to the book that you’ve heard so far?

I recently had an event at The Lit. Bar in the South Bronx where a lot of the people who were in the audience had already read the book. I was in conversation with another writer, Vanessa Mártir, and they wanted to hear the conversation. A lot of them were just there to express how it was the first time — for a lot of them — that they’d seen people like them in a book. People who grew up in poverty, too, who were Latino, who were Black and brown, who had struggled with mental illness or had a mother with schizophrenia or had suffered sexual violence. A lot of them were there just to say, “thank you for writing this book.”

You also include a lot of research and a lot of history that often gets left out of mainstream narratives. Why was it important for you to include this cultural history and research?

“I need to be accountable and do whatever I can with this privilege.”

My origins as a writer started with my father loving books and, for me, reading about the history of Puerto Rico from my father’s books and learning about this very early. This history deeply affected me and who I became as a writer. But also feeling like this history has been for the most part erased. It’s not something that we’re taught in school and it’s not something that Puerto Ricans or that Latinos learn, unless you go out and search for it. There are not a lot of resources. And, often when you find a history book, it’s not written by women, especially not women who grew up in poverty, so it’s not accessible to everyone.

I wanted to center this history in a memoir in a way that was accessible to all readers, in a way that felt like exactly what I needed when I was a young reader growing up thinking about our history. But I also wanted to share with readers how I myself as a Puerto Rican growing up in the diaspora, working as a writer, have been complicit in our own erasure. How I myself feel like I need to be accountable and do whatever I can with this privilege to share this with other readers.

What are you working on right now?

I am hoping to make an Ordinary Girls TV show. That’s up in the air right now. I wrote a pilot, and we are having a lot of conversations about it. That’s all I can really say right now about that. Of course, my dream would be to have an Ordinary Girls TV show that has a very inclusive writers’ room that’s full of queer, Afro-Latina and people of color writers that prioritize and center our stories.

I’m also working on a novel. Right now the title is I Am Deliberate. It’s about a girl who goes to college and also about some of Puerto Rico’s history. I’m also working on a bunch of essays. Some of them are about music and some are about love. I’m really interested in writing about good love and happy endings and something more positive and easier to write than what I’ve been working on all these years.