Ask several people with Latin American roots what term best describes us collectively, and you’ll certainly receive a variety of answers. Some will say we’re Latinos or Latinxs, while others will opt for Hispanic, and still there are some who will criticize these words for promoting a panethnic identity that erases their countries and doesn’t necessarily result in real camaraderie among people of Latin American descent. And while criticisms of these words are valid, the terms do have utility – even today.

“Some would argue that groups are powerful because they can organize by an identity,” Cristina Mora, author of Making Hispanics, Bureaucrats, and Media Constructed a New American, tells me. “With that, labels are important. This does not mean they are perfect, but it does mean that labels matter.”

Having a word that groups us into one category has been used as a political tool in the past, and this line of thinking certainly inspired the emergence of Hispanic and Latino in the United States. There’s a long history of naming practices for our communities, as Ramón A. Gutiérrez outlines in his essay, “What’s in a Name? The History and Politics of Hispanic and Latino Panethnicities.” Newspapers from the 1850s reveal that in San Francisco, for example, the term “Hispano-Americanos” appeared in ads. And after the term Latin America was coined around this same time period, the word Latino also came into use. However, as Mexican populations grew in the United States, Mexican and Mexican-Americans became more prevalent. “Hispanic and Latino, as abbreviated versions of Hispano-Americano and latinoamericano, flourished in California’s Spanish-language discourse during the second half of the nineteenth century but had virtually disappeared by the 1920s,” Gutiérrez writes.

For many decades after that, people of Latin American descent were referred to as their own distinct nationalities. And Mexicans and Puerto Ricans, for example, were categorized as white on the Census. This was a source of frustration for Chicano activists who argued that not having a separate category for people of Latin American descent meant they couldn’t show the government that they had separate needs. Mora’s research shows that activists, particularly the National Council of La Raza – now known as UnidosUS – lobbied the government for a term that would unite these varied groups. The organization was instrumental in uniting Mexicans and Puerto Ricans “to hammer out a Hispanic agenda,” Mora tells Latino USA.

The media also helped popularize the term. “The Spanish-language media was key to creating a narrative about Hispanics,” Mora tells Berkeley News. “For example, one of the most popular Spanish-language programs at that time was the Miami-based El Show de Cristina, billed as the Spanish-language version of Oprah. On the set, Cristina might have a Colombian family, a Mexican family and a Puerto Rican family talking about the difficulties of raising second- generation immigrant children or passing on the Spanish language and traditions. This created an image that we were together, that we share the same problems, that we are a community.”

After 1980, the Census created its first report on this group in the United States, and according to Mora, Univision used these figures – which activists originally hoped would show the needs of our communities – to show advertisers our buying power.

While the word Hispanic has helped bring some progress, it’s also been heavily criticized, even decades ago. Hispanic refers to anyone from Spain or Spanish-speaking parts of Latin America. It, therefore, promotes Spanish heritage, something many oppose because of the violent ways that they colonized our countries and the erasure of Afro-Latinos and Indigenous people. Today, some dismiss the word Hispanic and call it a government creation. This is something that Grace Flores-Hughes, the government official credited with coining the term, has spoken out against.

“There are many Hispanic activists who think that Richard Nixon did it,” she tells The Washington Post. “Well, no, Richard Nixon was very busy – he didn’t have time to be doing this. When I explain it [to other Latinos], they get relieved. They were holding this anger that some nasty Anglo named them. Well, no, it wasn’t. It was this little Hispanic bureaucrat.”

And though Flores-Hughes believes the word Hispanic is a much more accurate name for us, people have pushed back against this term for a long time and offered Latino as the solution. Latino refers to people from the Spanish and Portuguese-speaking countries of Latin America, but it does not include those from Spain or Portugal. This word, however, typically doesn’t make room for people from Latin America whose countries were not colonized by Spain or Portugal, leaving out Belizeans and Haitians. (There are some people with ties to these countries who do self-identify as Latino.)

Through a quick Google search, and largely thanks to Mora, it’s easy to pinpoint the start of the word Hispanic. But the origins for Latino aren’t as clear. Michael Rodríguez-Muñíz, an assistant professor of sociology and Latina/Latino studies at Northwestern University, says this is because there hasn’t been a “systematic study of the categories Latino, Latina (and the change to) Latinx. It hasn’t received the kind of attention that Hispanic has.”

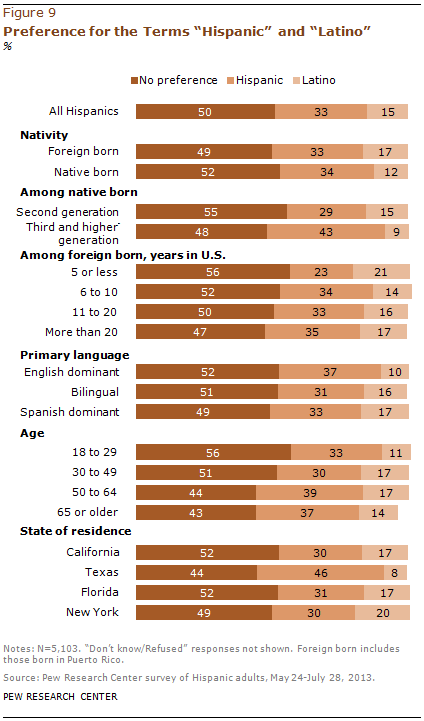

Across various age groups in our community, about 50 percent of people say they do not have a preference between Latino and Hispanic, according to Pew Research Center. However, those who did have a preference veered toward Hispanic in larger numbers.

But with Latino seen as a more inclusive word, it’s become necessary to describe our communities. Places like Chicago – which had and have a large Mexican and Puerto Rican population – helped bring about this change.

“Here, in Chicago, you had a lot of use of Latin, so without the O, for a lot of the ’60s and ’70s, actually,” Rodríguez-Muñíz says. “I don’t know if that was actually in play in places like Los Angeles. And so we see a series of labels that are circulating, percolating, and then through the processes that Cristina Mora described [in her book], we see this consolidation around the category Hispanic. And around the same time, we’re starting to see people using Latino. At that point, it’s not very clear what the politics are – in terms of what the difference is of Hispanic – but the point that’s of interest here is that you do have a moment where people are grappling, for a lot of different reasons, with the label to capture this population. And after the 1980s, you see this kind of tug of war between Hispanic and Latino. But a decade before, people were using Latin or people were using Spanish-speaking or Spanish descent, that kind of thing. But those kind of fell out of favor after Hispanic and then, Latino came to the fore.”

Since then, the term Latino has been adapted to become even more specific. For groups often excluded from the discourse, words like Afro-Latino, Muslim Latinos, and Asian Latinos have helped to center their experiences. It’s an example of the malleability of the words we use to describe ourselves. That’s why Latinx, a new(ish) word is now taking center stage.

In the last few years, the word Latinx has gained momentum – appearing in emails from politicians to TV shows like One Day at a Time to mainstream media. However, the word inspires many a heated argument. Latinx – which has existed online since at least 2004 – arose as a gender-neutral alternative to Latino and Latina. However, some believe that Latino already effectively groups a large number of men and women with Latin American origins and that substituting the O for the X unnecessarily complicates the language. And while the Real Academia Española – the official source on the Spanish language – may fall into this camp, Merriam Webster recently added the word to its dictionary.

In the introduction for his new book, Latinx: The new Force in American Politics and Culture, Ed Morales, a journalist and lecturer at Columbia University’s Center for the Study of Ethnicity and Race, writes, “The advent of the term Latinx is the most recent iteration of a naming debate grounded in the politics of race and ethnicity. For several decades, the term Latino was the progressive choice over Hispanic… For all of Latinx’s space-age quirkiness, the term has a technocratic emptiness to it that can make it hard to warm up to. It feels like a mathematician’s null set, and many are unsure of how to pronounce it. But even amid ongoing debate around the term on campuses and in the media, the growing movement to embrace Latinx highlights how it dispenses with the problem of prioritizing male or female by negating that binary. The real power of the term and its true meaning, however, erupts with its final syllable. After years of Latin lovers, Latin books, Latin music, and Latin America, the word describes something that is not as much Latin – a word originally coined by the French to brand non-English and Dutch-speaking colonies with a different flavor – as it is an alternative America, the unexpected X factor in America’s race debate.”

The conversation of Latinx has mostly revolved around whether this word makes sense and how to pronounce it. It has even sparked a host of think pieces arguing both sides of the equation. And while Latinx comes with heavy scrutiny, for those who are non-binary, it helps them feel seen.

“Being Latinx is to exist outside the binary, to be somewhere on the spectrum but still feel a solid place in it,” Em Alves tells Latina. “Being Latinx is to feel solid in two or more places. For me, it’s embracing the rich and beautiful culture of our people, while rejecting the gender restrictions of the generations before us. I identify as a queer, hard femme Latinx, and my Latinidad is such an integral part of how I experience my gender and sexuality. Latinx acknowledges me for who I am, in all my parts.”

But regardless of the very compelling arguments made for Latinx, there are still many who remain reticent – or outright resistant – to the word.

Through my conversations and research into the background of these terms, it became clear that the origins and evolution of what we call ourselves is as complicated as our history in the United States. We’ll probably never find a perfect term, especially as some prefer to identify as their (or their family’s) country of origin. “I think it’s important to both really work on what is your Puerto Rican identity, what is your Dominican identity, what is your Colombian identity,” Morales says. “But at the same time, work on what is Latino identity. I think it’s a mistake to stump one in favor of the other.”

And while the language we use is important, perhaps what matters most is whether or not these words are helping us fight for everyone in our communities.