At its core, music is energy expended, energy created and energy harnessed. And that power to excite carries on a different meaning to people who are oppressed in autocratic regimes. From the Beatles effect on the Soviet Union to the improbable reach of Sixto Rodriguez in South Africa, the topic has been covered periodically and it’s easy to see why; they are feel good stories of music’s power to transform lives for the better.

Then there’s Radiolab.

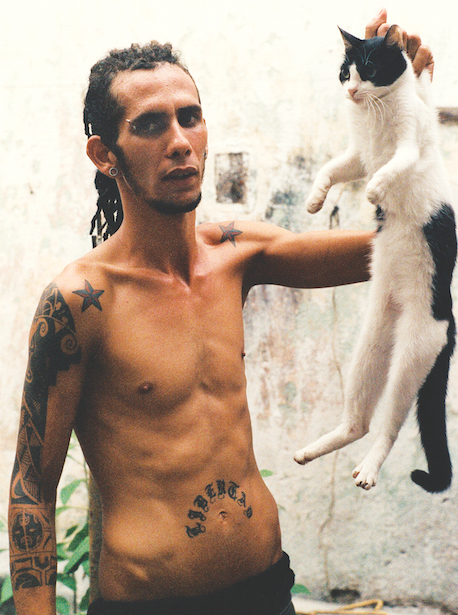

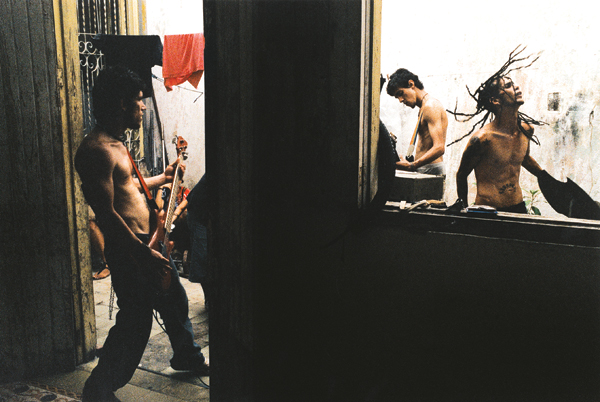

The WNYC podcast – which we recently profiled here – is, in a nutshell, amazing. Last week, they released a new episode titled Los Frikis, exploring the story of Cuban punk rockers in late 1980s Cuba who deliberately injected themselves with HIV. Part political protest, part response to a helpless situation, and part mass hysteria, Radiolab went into detail about a phenomenon that ironically paralleled Socialism’s painful death.

The story is fascinating and also represents a milestone for Radiolab: its first collaboration with Radio Ambulante, the narrative Spanish-Language radio show that has often been compared to This American Life. (Check it out here; it’s real good stuff and its web page has a much more in depth story on the so-called Los Frikis).

We caught up with Radiolab co-host señor Jad Abumrad to get a better understanding of how this collaboration came about, the power and limitations of music, and last but not least, the punk rockers who gave their lives as a, in Abumrad’s own words, “double fuck you to the government.”

How did you even hear about this?

One of our producers, Tim Howard had met Daniel Alarcon from Radio Ambulante. They struck up a relationship and they were having a conversation for a while about somehow creating a collaboration. We went through, God, maybe five, six ideas with them, mostly with Luis Trelles as the main reporter. They had stories about the Puerto Rican Justice System, stories about a transgender – bigender person, I think – living in Venezuela, I forget where exactly. Stories that sort of ran the gamut and this was on the list, this story about the Frikis in the late 80s. The question was always, could Luis find somebody to talk to, to get us a bit closer to the story. I don’t know how exactly but at some point, he called us up, he says ‘hey I managed to locate somebody’ who knows the last two survivors from this movement if that’s what you call it. We were like, that’s enough, get on a plane go to Cuba and see if you can find them. And he did find them.

If you’re making a strong political statement that ultimately causes more harm to you than to the system, is it worth it?

When you look at this, it’s a political protest but there are some parallels to another Radiolab story, Patient Zero where people who infected others saw it in a way as an inevitable death, a sort of nihilist way to look at things. Is that a valid reading?

Honestly, the thing that caught my eye on it came more from the musical angle. I’m a fan of tried and true punk rock in this country, but I’ve always had complicated feelings about it. It’s this rejection of everything but, there’s something sort of wasteful about that. It’s these young people wasting their lives, wasting their youth but at the same time, it’s this powerful political statement of opposition and I always found it really interesting. And when I heard about this story, it felt like on the surface like the purest expression of Punk Rock that I’ve ever heard. I was just really interested in telling it as a cultural story but also a story about someone expressing something essential about the music. That’s where it started for me but then as we were working on it, I became really interested in the politics and the history of America and Cuba’s relationship. But that’s not a story you can easily tell, you need some way, some pinhole through which to experience that and these kids became that for me.

What was the relationship between this subculture and the government at the beginning; did they see them as harmless eccentrics or was it always seen as some sort of threat?

When this sort of cultural war against the “anti socialists” began in the late 80s, Castro’s government cracked down on a whole bunch of people deemed anti-social [including] these kids, who had long hair and liked to listen to rock. Their responses at that point were to toss people in jail for the night, or fine them, or sometimes to beat them up or force them into manual labor. Then, when some of them began to self inject, based on what we could find, it seems they were…I wouldn’t say ignored by the communist government, but once they were in the sanitariums in the early 90s, it doesn’t sound like those sanitariums were run directly by the government, or at least not by the military. They were run by the ministry of health, I believe, which was staffed by a bunch of progressive doctors. And so, they were living in this weird little utopian bubble where they could have all the medicine and food they wanted, and listen to all the music they wanted, and I don’t think the communist government knew about them. It seems to be that at a certain point as the movement got under way and you went from just a few self-infected frikis to hundreds, there’s evidence that Castro was told about it, that he was frightened about it, that he outlawed the use of syringes in those areas and they put these mandatory jail sentences for anyone that was caught self-injecting. Because if you think about it, it’s horrible PR. If you’re trying to convince the world that the socialist regime is the righteous and true path, it’s a terrible thing to have people learn that the kids in your midst are choosing to die. So, I think it was very frightening, although it’s very hard to say with any certainty. As the movement picked up I think it became a thing that reverberated outside the sanitarium.

Radio Ambulante could get access to the story we would never be able to get.

In a weird way, the situation in the sanitariums was a sort of Punk Rock version of Prague Spring; the people in there didn’t have to put up a front and they felt free to express themselves. Did you see that connection?

I didn’t make that connection until just now. I don’t know, I mean, for me, it’s sad really. If you’re making a strong political statement that ultimately causes more harm to you than to the system, is it worth it? I don’t know if I have an answer to that because I still see what [some of] these kids did as being strong and fierce. But I also see it as being simultaneously very tragic and sad and naive, in a way. I don’t know where to come down on any of that. That for me was the part that felt like in some way, Punk Rock in this country had the same qualities. And I always think to what extent does a movement need to be naive to create a kind of energy that can actually make something happen?

How did President Obama’s announcement affect the project?

We wouldn’t have been able to do the story from our angle. I don’t know if that changes now. I honestly haven’t investigated too much in what the on the ground differences are in terms of travel. I’m ashamed to say, I don’t exactly know what has normalized when he normalized relations. That was one of the real beauties of collaborating with Radio Ambulante. They actually could get access to the story and we would never be able to get access. For me, Radiolab right now, that’s what it’s all about, it’s about getting out into the world and getting access to places we would never get to go and engage in things and not just sit in a studio and thinking big thoughts but actually going somewhere. It was really exciting to do that with those guys.

Last time I spoke to you, you were afraid that Radiolab might not have the cultural authority to do these types of stories. Now that you’ve worked with Radio Ambulante, do you have further plans to collaborate with them?

I’d love to collaborate with those guys a lot. Who knows what’s gonna happen but we’ve been talking to them for a long time and we have a bunch of stories thought through with them. If I had my way, we’d do a series, a long series of collaborations with those guys. There are stories that they are telling that are hard hitting, they’re exciting and they’re completely off our radar. I want those stories on our show. It’s a part of the world that I feel there’s so much that’s interesting and exciting and troubling that’s happening and I want to be able to know about it and to tell my listeners about it. It’s always a question of logistics. These types of stories take six months to a year sometimes and we’re all such small teams. It’s my commitment to do these kinds of stories. I definitely anticipate doing more of them. We’ll see!

Are there any specific stories that you are thinking about with them?

We’ve talked about having a look at the Puerto Rican Criminal Justice System and there’s a story where if I could wave my magic wand we would do tomorrow – but some of the characters in the stories don’t want to talk. So there’s some stuff that we have on our radar, but nothing has really popped yet. They did a Spanish language version of this story for Radio Ambulante which went in a different direction. I’m pretty sure what we’re gonna do is release that story in our stream as is. We’ll probably release it as a video with subtitles for our mostly English-speaking audience. I’m excited to draw our audience to them. I’m also excited to be tip-toeing our way into what it would mean to speak in different languages frankly. It’s something that we poked at in the translation show. I like the idea of it. We might put that out quite soon.