“I run to follow as closely as I can the path of those who came before me,” wrote Mexican-American author Noé Álvarez. “Migrants who knew suffering and deprivation. Still, I run to find fragments of my own parents over the earth, artifacts, their stories of hope and desperation…I want to learn how to embrace my past, where I came from and to love myself again.”

Noé Álvarez is from Yakima, Washington—a city named after the first inhabitants of the land it sat on. His parents, immigrants from Mexico, worked in agriculture there, picking and packing interminable quantities of apples. After many summers of work alongside his parents, Álvarez got a scholarship at Whitman College, a small liberal arts college nearby. But, after a year of feeling out-of-place and lonely, he learned about Peace and Dignity Journeys (PDJ) and decided to run across North America as an ally to the handful of Indigenous runners that undertake the journey every four years.

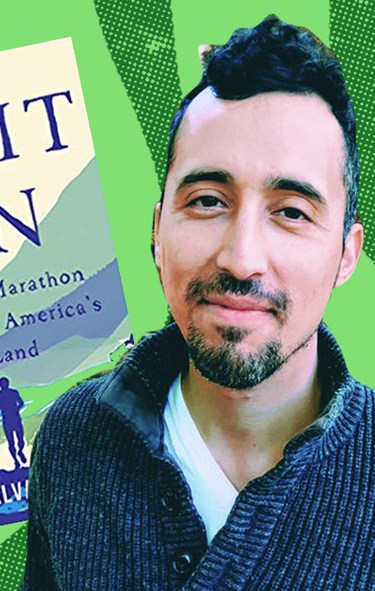

Álvarez began in rainy Canada and ran all the way across the Mexico–Guatemala border. His new book, Spirit Run: A 6,000-Mile Marathon Through North America’s Stolen Land, tells the story of that run and what he learned from Indigenous communities and ways of thinking as he pushed his body to its limit.

The book is a gorgeous rendering of both the physical challenges involved in running 6,000 miles as well as the different kinds of landscapes Álvarez and the PDJ crew traversed—from the wet, green forests of the Pacific Northwest to the city streets of Los Angeles, deserts of Northern Mexico and rainforests of Southern Mexico.

It also explores probing questions around identity, allyship and belonging that he uncovers over the course of his journey.

Álvarez spoke to us about running as a way of healing, how to write through and around stereotypes and how running across an entire continent as an Indigenous ally changed his life.

How did undertaking the Peace and Dignity Journeys challenge change who you are today?

The United States is accustomed to reading stories where there’s a resolution and that’s just never been a reality of mine. You just take it a day at a time, one step at a time literally and figuratively, so I think it’s still a work in progress. I think my parents really taught me that and even when I presented this book to them… it’s in English and they won’t be able to read it, but the cover is pretty! And they were really happy, but then immediately she’s like, ‘Qué quieres comer, mijito?’ like always and that was her way of celebrating it.

We’re really stuck in these rhythms of suffering and, for many of us, it’s all about developing a ritual around things that matter—around community, around landscape. I think that for anything to become healing—for me, it was running—you have to work at it and it’s hard work. I’m still giving it a shot, still going through my moves and still making my mistakes, but I wanted to do my best to get the story out there so that people know anyone can do this.

I know that you mention that your father descends from Purépecha people, but you ran PDJ as an ally—what did that look like or mean to you? How did that affect how you ran? How was your relationship with indigenous rights, with land rights affected by the run?

It was very difficult. It took me many years to get this out because that was one of the questions that I had. Who am I to write this story? I decided to weave in the narratives of other people—the others on the run with me, because I wanted to give a platform for others. I’m not speaking for [Indigenous] people and I don’t want to rob people of their voice. Instead, I want to introduce or re-engage a conversation. This run has been happening every four years and many hundreds of people have participated in it, so I hope that this is only the first book. I hope that more books come out from different indigenous communities.

One of the things for me personally was that I had this fear of immortalizing my own family in this sort of negative legacy, the story of work. I didn’t want to create an archetype of anybody—my parents aren’t a representation of that side only. I’m still navigating those waters. I’m not sure how I feel. But I know that I was very concerned about outing my family as far as what they’re doing. My mom’s still doing warehouse work and that bothers me every day. It’s like things that keep you up at night. Those are the sort of things that will keep me up at night. I don’t want to trap my family in that narrative and I also don’t want to trap other people in that. So, at the very least, I want people to ask about those other folks and give them good momentum that they need as well to tell their stories.

But at the same time, Peace and Dignity has these very private ceremonies, very private get-togethers—you have to respect the traditions of a lot of people [and] ask permission to take part. That’s still very much the case, which is why a lot of people don’t know about Peace and Dignity, but it’s also very much a public gesture. We’re running through land, we’re physically showing ourselves because we’re in that time. For a long time we’ve needed to announce the struggles of our communities because people are [disappearing], people are not hearing what we’re saying. There’s very much a public ceremony aspect of this. So for me, Spirit Run is that public aspect of what Peace and Dignity meant to me specifically.

I really appreciated how you started with all the stories of the runners in their own homes and their own contexts and then really anchored us in a place that was home to you before taking us on a journey with you. Can you talk a little bit more about how that structure happened?

If running really is a healing act when you’re dedicated to the people, if it’s all about community, then it needs to be represented in the structure. How can I say it’s all about community and then not have them integrated into the structure itself? I wanted to structure itself to explain you’re physically carrying it forward with you.

During the run, we carry bundles of feathers, which basically equate to a bundle of stories. In the beginning, you start with three feathers. In Alaska, you go to McCall and get the condor feather and then they just add feathers. People contribute stories, prayers to it and then it just literally gets heavy. You’re literally carrying the weight. It’s a physical reminder of why you’re running. You are part of a community firmly weaved into all that.

Also, as far as the shorter chapters, I grew up in a sort of world of fragments. My parents told me about a lot of things and didn’t tell me a lot of things either. But I saw. I was making my own connection, so even though I didn’t have a complete picture as a kid, it was what drove my narrative. It was what drove my reality. It didn’t really change [who] I became as a person because we operated in this whole world of fear that you can be disappeared, that you can be deported. Even when my parents became citizens, [we still had] folks and relatives around us and you’re fearful for them and you didn’t know that your status would change in a day. So, going back to the structure of Spirit Run, part of it is trying to piece together and give shape to that pain and those fragments. I wanted to show in those threads that I’m just trying to rearrange our relationship to how we saw and how I saw myself as a kid.

I noticed that these ideas around community are also woven into the plot of the book—a lot of your running requires you to be vulnerable, to allow the communities that you run through to provide support, food, all these other really basic needs. Can you talk a little bit about what it was like to encounter and be welcomed by all these communities and rely on them for your sustenance and shelter?

That was my fire.That was the driving force behind it all. The beauty behind the power of a community welcoming you in full force. My first run, mile after mile, I didn’t know what to expect every day. It was new every day. And sometimes I would have a really tough run, a really tough encounter where I’m hungry, tired or whatever, then you get there and you have this whole community waiting for you at the gates or with music and drums… powering you on. You’re like, ‘Wow, this is what it’s about.’ This is why [I’m] running.

And then you sit there and you have a ceremony with them, you do a potluck with them, you listen and you sit in on their community discussions. They bring in their elders, they bring in their community, they share stories. It was like running to reach the next story. Every community was an opportunity to sit and listen to what they were going through and some of the battles that they were going through. It was all about them giving us a story and giving us a prayer for us to remember that story by an and then continuing on. It was like, ‘This is why you’re running,’ and you forget about your pain.

For me, it’s kind of hard to run in the city, but I found my peace and my prayer in nature and that was a constant reminder that I need to do it with people. I think all runners have that understanding, but it’s so much more powerful when you do it Peace and Dignity style when you have just a whole community behind you… It’s just this whole new way to be with people who have life figured out.

Correction, March 5 at 12:15 p.m. ET: This post has been updated. The author attended Whitman College, not Wheaton.