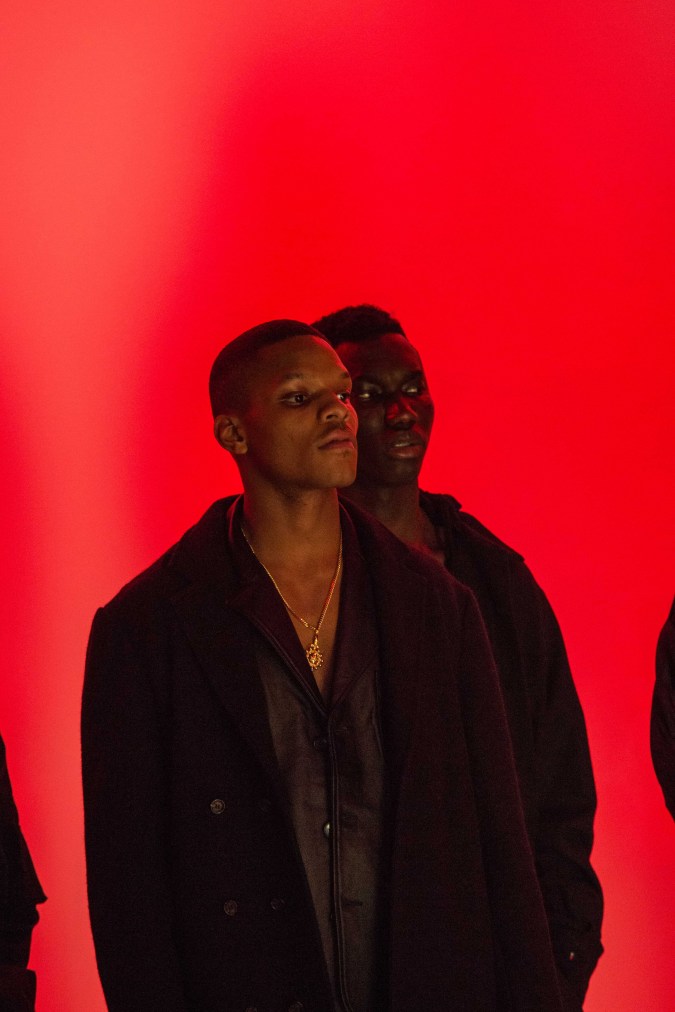

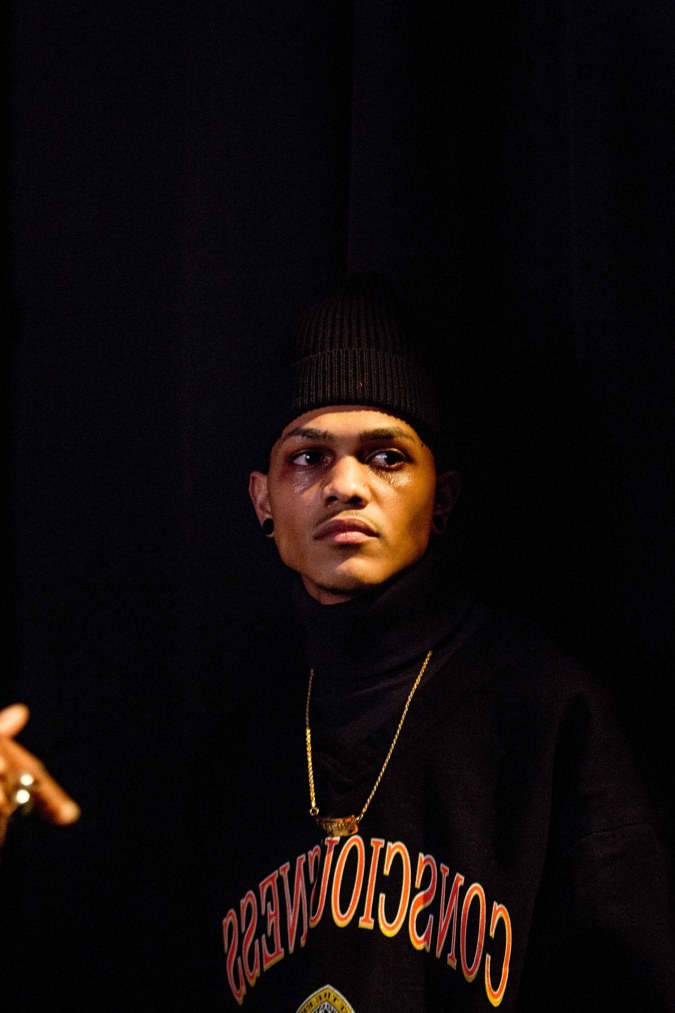

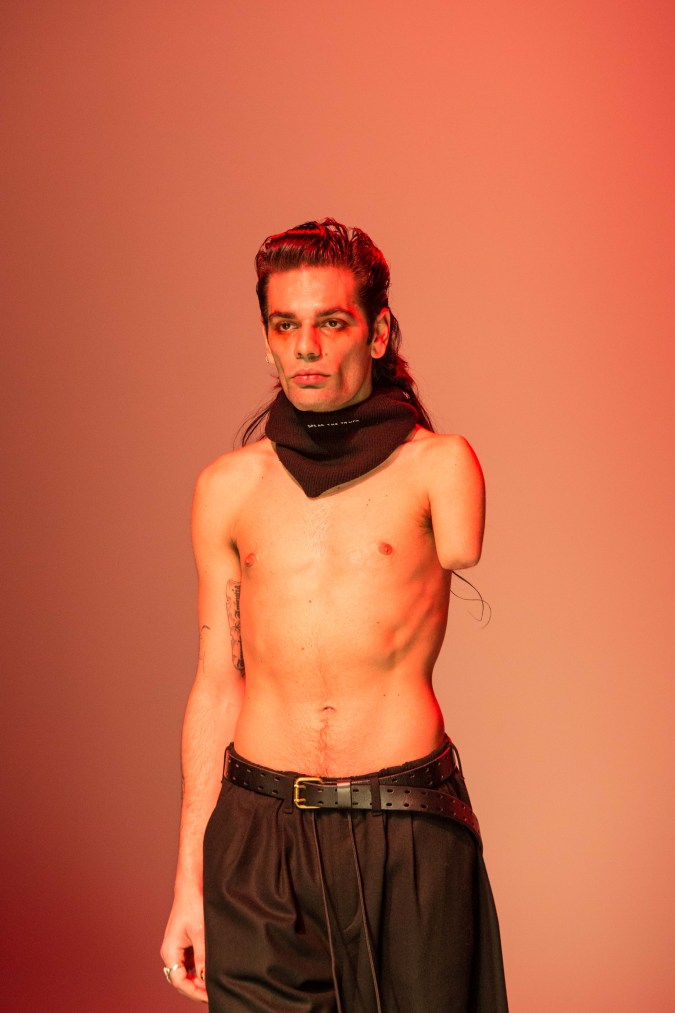

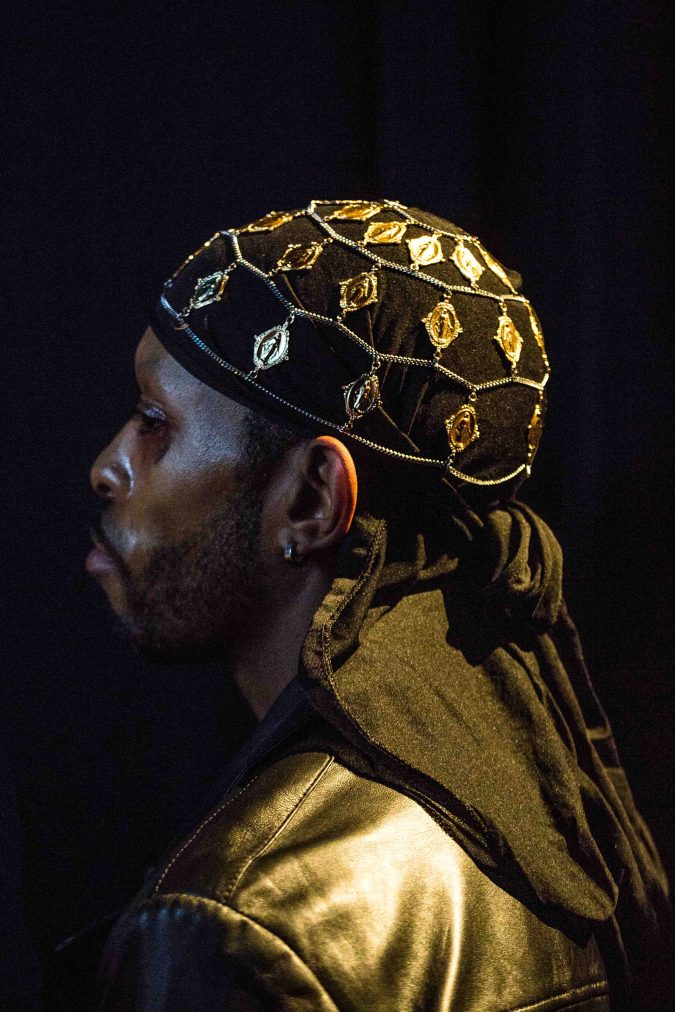

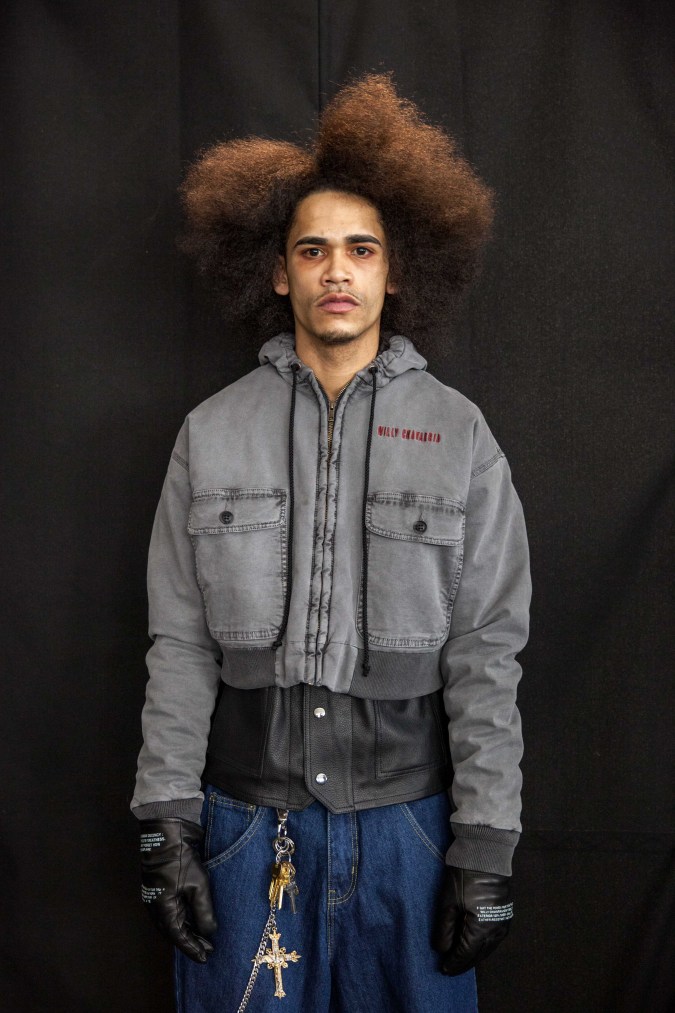

At this year’s New York Fashion Week: Men’s, Willy Chavarria’s black and brown models with eyes red and swollen cried on the runway. Foreboding instrumentals set the tone for a presentation titled Believers, where model after brown model – cloaked in takes on classic uniforms of the street – showed us a vulnerability not often paired with men of color.

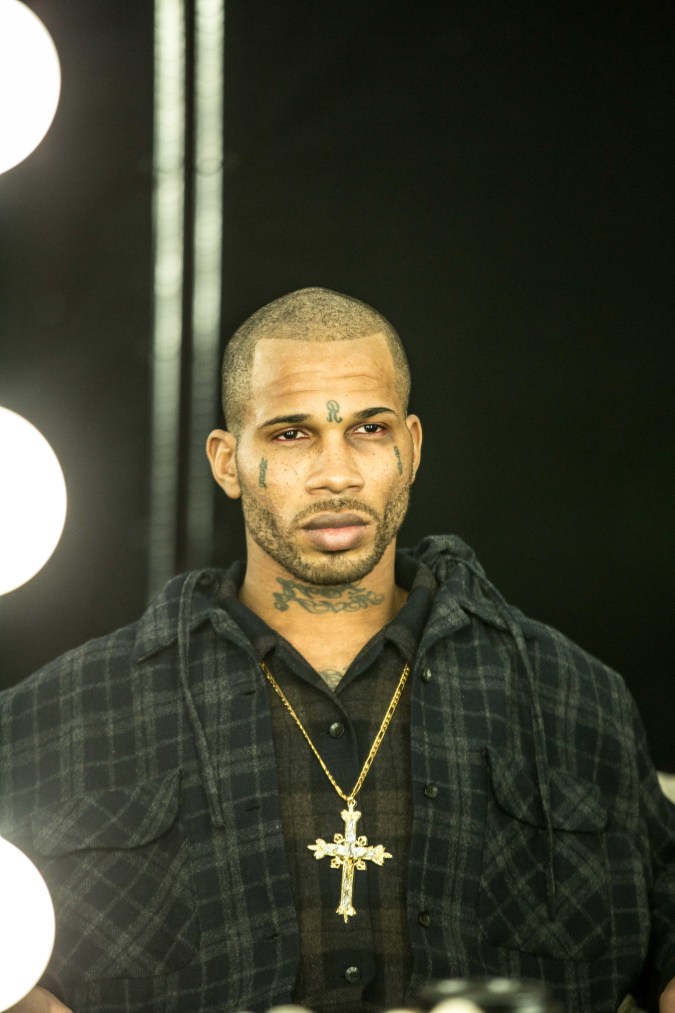

Following the designer’s tradition of using personal and societal unrest as inspiration, Chavarria’s show drove many to contemplate the co-existence of anxiety, emotional depth, and beauty in communities of color, which are often the uncredited source of fashion innovation. As models strode forward, their tattooed faces dripping with tears, it was impossible to not think about all the men wrongly accused of crimes; the ones targeted by police; the ones caught in the prison industrial complex.

“There is a dark feeling in the show because there is a collective feeling of depression especially among brown people right now,” Chavarria tells me. “There’s a lot of hate speech being hurled around. We got this whole White House situation. There’s a giant raining of negativity and I didn’t want to ignore that in this collection. I wanted to acknowledge this feeling and take people who are enduring this and show us as being strong. Sad but strong.”

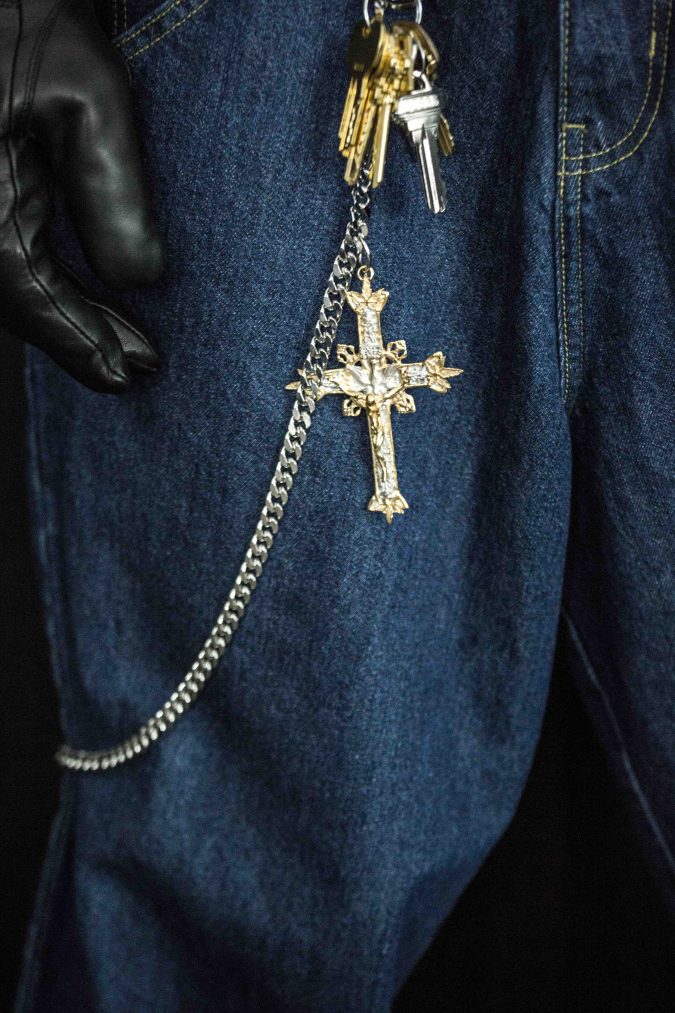

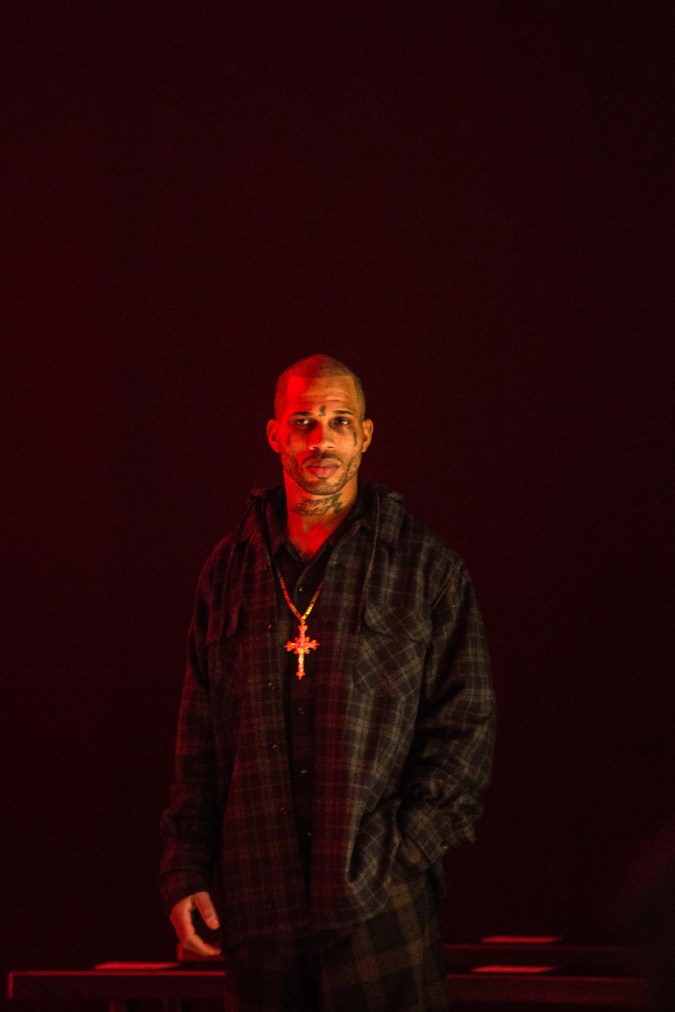

’80s-inspired leather jackets functioned like armor over the traditional ’90s baggy jean, with swinging wallet chains, golden crucifixes, coke spoons, and shanks as accessories. Some models wore facial chains and grills, a collaboration with Chicano jewelry designer Chris Habana.

Many of Chavarria’s designs take inspiration from his Mexican-American background as well as the farmworker communities of Fresno, California. This line had billowing trousers with tapered ankles referencing pachuco style, and the classic Chicano workwear look of layered plaid patterns on oversize jacket pant sets.

“It made sense for me to draw on things that inspired me from my history,” he says. “My favorite looks being the California Texas Chicano influence styling and fits which emerged into the clothes: baggier pants, oversized top, muted colors.”

However, Chavarria doesn’t just recreate traditional designs, he’s challenging stereotypes and giving these looks context. So often in fashion we see Chicano culture mined for trends that come off as watered down and ingenuine when used by white designers. Think the Kardashian clan’s appropriation of every fad that originated in Black and brown subcultures. “I try to give credit where credit is due,” Chavarria adds. “I take the styles in their most raw form on regular people, alter them, and elevate them by using beautiful fabrics and washes. Taking things that are already from the street, improving them, and making them high fashion.”

Beyond using elements of style from working-class communities, Chavarria puts models of color at the forefront. “The brown people I use, the women, the trans people, I want to put them on a platform of elevation,” he states. “What I do is different because there’s a sincerity. I’m glorifying my own people, and giving back to my own people – showing us in a light that is intelligent, sophisticated, and thoughtful. It’s not just clothes.”

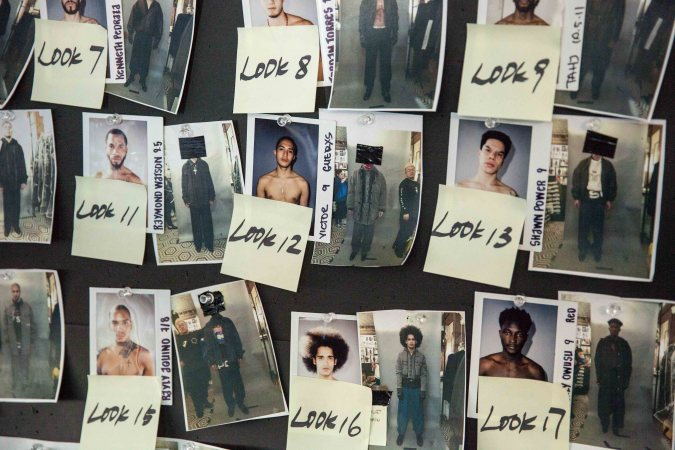

Chavarria doesn’t look for models at traditional modeling agencies, which tend to have overwhelmingly white rosters. Chavarria and his friend, Brent Chua, instead look to Instagram and the streets of New York City to cast their models. Chavarria is drawn to those who have interesting stories, who know what it’s like to fight and struggle.

From the projects in Fresno to working in the Ralph Lauren studios to owning his own brand, Chavarria has stayed focused on his vision. With his brand only in its second year, he’s still considered an emerging designer. Japanese retailers and Barney’s in New York have already picked up his designs. However, not everyone has received his work well. He experienced some homophobic backlash for his last line, Brown Power.

“There are a lot of haters out there,” he says. “I think any time you’re making changes or pushing forward, you’re going to get some people who really are not down with it. My portrayal of Chicanos was outside of the stereotype from what they’re used to. Chicano art has to look like Mister Cartoon or have to be that kind of thing.”

Then, there are those who see fashion as just another arm of capitalistic consumption. But fashion has always served as a way to resist, rebel, and politicize your body. Historically, this was also the case for brown people in the United States. From pachucos dressing in elaborately tailored suits and draped fabrics in the Depression Era so they could assert an identity at a time when society treated Mexicans like second-class citizens to cholos having street uniforms of khaki Dickies, Pendleton button downs, and muscle tees as a way to signify cultural unity and combat assimilation into whiteness. Why wouldn’t we expect high fashion designers to reflect political discontent? Chavarria does.