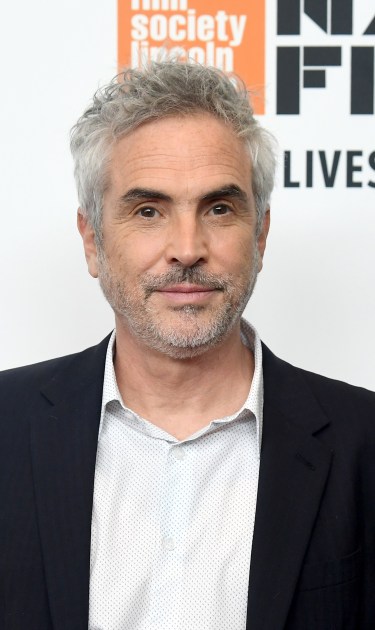

Longing to recapture his childhood impressions of Mexico City, capitalino director Alfonso Cuarón harnessed his memories as the foundation of his black-and-white magnum opus Roma. He created fictionalized versions of the individuals that shaped him, whether through affection or even abandonment, paying close attention to find actors that resembled his family. Even going so far as to recreate an entire street to approximate what it looked like in the past, the director also used relics from his childhood like a luchador action figure to complete the sensorial immersion in 1970’s Mexico. His early years are projected on every sumptuous frame, drawn with permanent light on-screen to stand the test of time.

That includes his love for Cruz Azul, a fútbol team that is always this close to winning but never quite gets there, leaving its hinchas hungry for victory. Back in Cuarón’s formative years, however, La Máquina were consistent champions and he was a fan. “Cruz Azul was my team as a kid. I mean, it’s still my team but now I’m more of a villamelón,” he told Remezcla over the phone just days before the 91st Academy Awards.

As a villamelón, a colorful term to refer to fair weather fans, Cuarón admits he doesn’t follow the sport as closely as before he was directing masterpieces on a global scale, but there is one person in his family who remains truly passionate. “The real diehard cruzazulero is my brother Carlos,” he explained. Testament to that is Carlos Cuarón’s fútbol comedy hit Rudo y Cursi, starring Gael García Bernal and Diego Luna.

Fueled by unbridled adoration, Mexican club soccer offers plenty of room for intense rivalries. One of the most pronounced, is that between two chilango teams, Cruz Azul and América (a club reviled and adored in equal measures). Another Oscar-winner, Alejandro González Iñárritu, is famously an América fan. When asked if there is any animosity between him and his americanista friend, Cuarón responded in a hilariously deadpan tone: “Iñárritu is a great filmmaker and a great person, but he has profound character flaws. That’s one of them.”

Cruz Azul, a popular brand of locally produced cement that gives the soccer team its name, is also prominent in Roma in the form of ads that appear throughout the film in particular the scenes that take place in Ciudad Nezahualcóyotl where Cleo (Yalitza Aparicio) visits Fermín (Jorge Antonio Guerrero). In the early ’70s, the area was a poverty-stricken slum with limited access to basic services.

According to Cuarón, Cruz Azul cement was a very constant presence during the construction of that community, and in Mexico in general, at a time when the country was heavily investing in infrastructure. “Another relevant aspect about Cruz Azul cement is that it was one of those successful experiments of a cooperative,” he added regarding the company’s business model where all of its members share profits equally.

Painstakingly constructed down to its most minuscule items, Roma stands as a nearly faultless historical recreation of a city and its people in flux. To that end, it was vital for Cuarón to replicate the way people in Mexico City talked several decades in the past. Though the cadence of speech hasn’t changed, the slang has evolved. Still, he didn’t find the task to be challenging since he tapped into what was organic to his experience growing up.

“I think in chilango. I speak in chilango,” effusively said the director. “It would be more difficult now to try to capture the current jargon, but I made a movie about my childhood, which made very clear the changes that have happened.” With that in mind, Cuarón pointed to a specific adjustment in the language currently used across Mexico. “When I was child the word ‘guey’ was a swear word. Now, guey is used everywhere,” he explained. “Back then there was a more reserved Spanish in terms of swearing. Today, certain words that were considered swear words back then are used very casually.”

To share his intimate recollections with those outside the Spanish-speaking world as best as possible, Cuarón was also heavily involved in the English-language subtitling of Roma, a job he considered painful. First, he started with a literal translation of the dialogue, but that didn’t work because of its duration in relation to what takes place on screen. “The issue with subtitling is that it’s not only about translating, but also about creating a rhythm,” he noted. His priority was keeping the audience engaged with what was happening on screen: “If you have a viewer that’s too worried about reading the subtitles they are going to stop reading the image.”

One of the more curious subtitling choices, was translating the word torta to taco. “What happened was that it was very clear to me that English-speaking, international audiences wouldn’t understand the word torta,” Cuarón acquiesced. “A gringo or a British person doesn’t know what a torta is, but they do know what a taco is.” It was important for him to express that the characters were indulging in comfort food, and didn’t want any confusion to get in the way. “I didn’t want the distraction of having the word torta and leave people wondering what a torta is.”

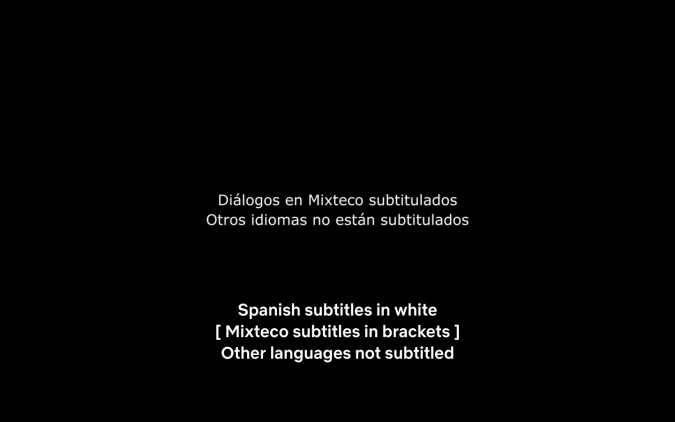

On the subject of language, he also discussed the reasoning behind using brackets in the subtitles to clarify when the characters speak Mixtec versus Spanish. “For those who speak Spanish, the only subtitled dialogue is that in Mixtec. But it’s very important for the audience that doesn’t speak Spanish to denote that there are two distinct languages in the film,” he clarified.

Aside from accuracy, what the director wanted to portray was that Cleo and Adela (Nancy Garcia) only used the Mixtec language in private. “It’s a language they use only in their intimate moments, or in the kitchen, or in their bedroom. The only moment where they speak their language in front of another character in the house is when the kid tells them to stop talking that way.” Cleo, said Cuarón, only shares her indigenous tongue with the young girl of the family. In the larger context of Mexican society, this is much more relevant. “The language also implies a power dynamic,” added the director. “Social classes are linked to ethnic identity. Ethnic identities in turn are in many cases linked to a language.”

From his position in the director’s chair, Cuarón also used his power to challenge the media scarcity faced by Mexico’s indigenous people. He confirmed there is a plan to create a version of the film subtitled entirely in Mixtec.

Now that Roma‘s awards season cycle is nearing its conclusion, with Oscar night almost here, the director is ready to return to his loved ones after months on the road. For the foreseeable future he will be tending to them. “My next project will almost certainly be in Europe because I have children, so I can’t be away for that long,” he said. “With Roma it was very difficult, the distance became a problem. I’m going to wait a few years until my children have their independence and then I’ll surely return to Mexico to make another project there.” We’ll be waiting.