Far-right politics in Latin America has evolved from its anti-Communist days into a reactionary ideology poisoned with xenophobia, Islamophobia, and racism, not unlike what’s currently proliferating across the globe. Araña (Spider), a new politically minded drama from director Andrés Wood (Machuca, Violeta se fue a los cielos), tracks the fascist doctrine back to 1970s Chile and follows its ramifications into the present.

Juxtaposing these two timelines, screenwriter Guillermo Calderón, who’s cowritten several features with Pablo Larraín, spins a web of deceit that traps a trio of characters first fused by a common cause and then divided through romantic woes. In the face of their fervor, both in their beliefs and their feelings for each other, hung the future of a country.

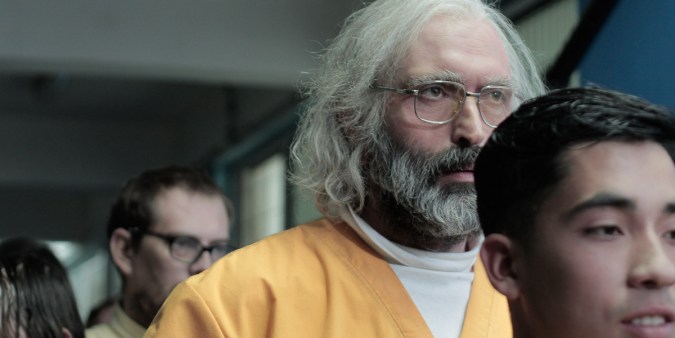

Long-haired and disheveled, middle-aged Gerardo (Marcelo Alonso) drives through Santiago disgusted at the sight of poverty and crime, à la De Niro in Taxi Driver, until he impulsively kills a purse snatcher in a self-righteous outburst. His arrest sends shock waves through the Chilean oligarchy. Businesswoman Inés (Mercedes Morán) and her ill husband Justo (Felipe Armas) are especially aggravated for his resurgence means a portal into a buried mortal sin born out of their flag-waving love triangle.

Alluding to the logo of Fatherland and Liberty (Patria y Libertad), a short-lived radical group implanted by the CIA in its efforts to destabilize Salvador Allende’s government, the titular spider works as a metaphorically inextricable link between the former companions. A turbulent shared past acts as an enduring cobweb.

Flashbacks to their youth reveal a sizzling dynamic defiance and a hunger for provocation, particularly when dealing with symbols of left-wing politics like the image of Che Guevara. Beauty pageant contestant Inés (María Valverde) and her offbeat boyfriend Justo (Gabriel Urzúa) bring air force veteran Gerardo (Pedro Fontaine) into the fold of the organization even if their convictions emanate from distinct places. The couple embodies the entitlement of unearned wealth, while the stern pilot’s background seems closer to the proletariat.

Polished in a serviceable manner, Spider has a studio feel in the way that it avoids much visual stylization other than the inclusion of black-and-white archival footage to contextualize what’s being fictionalized. Lighting falls flatteringly on the film’s subjects, but fails to emphasize or create a perceptible mood in either period.

Wood’s focal concern lies with the structural clarity of his split narrative, so that the contrasts in the lives observed 40 years apart are understood as part of the same unit. As expert editor Andrea Chignoli opens and closes chapters in the sordid bygone era and the hypocritical present, their toxic interactions become more ambiguous, despite her repeated usage of fade-to-black transition coming off as an unfavorable preference.

In the shuffle between then and now, what’s starkly apparent is how Inés and Justo leveraged their involvement in the events leading to the coup d’état that put Augusto Pinochet in power to maintain their superior standing in society. They are as retrograde as ever, but now without the roughness around the edges they exhibited as young adults. Terrified of losing face, Inés pulls strings in high places, the press included, to silence the truth. Old friends hide in influential circles.

Less prominent but just as telling about her psychology is her constant fight against misogyny. She is a bigot like the men around her, yet still a woman. With rumors circulating, colleagues turn their back on her, which calls back to an earlier scene in the 70s when she expressed her wish to have been born male. Morán maintains the spunk of her younger counterpart in a contained version suited for someone with plenty to lose.

Yet, for the intensely committed Gerardo, who went through irrational lengths to attest to his loyalty, nothing has changed. His extreme ideals have shifted their target to the influx of Haitian refugees into Chile in recent years. “This is Chile! And here we speak Chilean!” he yells inside a church where immigrants gather to pray in their own language, a phrase and situation that could appear taken directly from headlines birthed during the Trump administration.

Long gone is the Gerardo that once put up with Justo’s relentless humiliation in service of the movement. With isolation and resentment brewing inside him for decades, he’s living proof hatred doesn’t just fade away. Of the character’s two on-screen incarnations, Alonso’s embittered and weathered portrayal of a time bomb of a man prone to violence is the most piercing.

Standard as it often feels in its design, Wood’s solidly realized look into the human element of a horrid turning point in his nation’s recent history succeeds at comparing different courses of action for modern society’s villains cut from the same cloth: some normalize their prejudiced stances in mainstream arenas while others take to the fringes of civilized behavior to materialize their agenda. Both evils destroy, but is one of the legs of the same spider more venomous than the others?

Araña is Chile’s submission for Best International Film at the 92nd Academy Awards.