De lo mío is a delicate drama that wears its heart on its sleeve, with subtle outbursts of nostalgic joy. Through the film, Dominican-American writer-director Diana Peralta dives into a personal exploration of conflicted Latinx identity that seeks to honor the greatest qualities of her family’s homeland, while also trying to understand how its perceived by those with ties to it, but born and raised elsewhere.

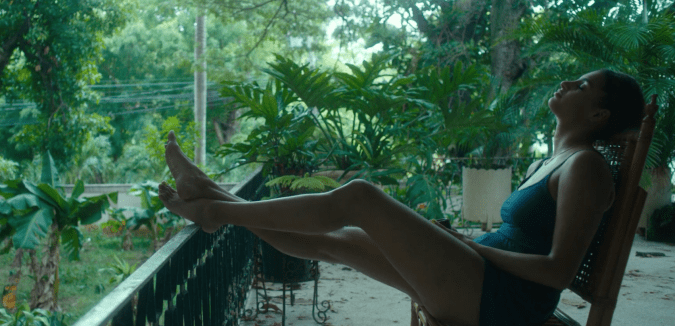

Two Dominican-American sisters, responsible Rita (Sasha Merci) and cheerful Carolina (Darlene Demorizi), arrive in Santiago, Dominican Republic from New York to help their older half brother Dante (Héctor Aníbal) clean out their grandparents home before it’s sold to be demolished. As soon as they arrive, Rita and Carolina bathe themselves in bug spray and continue to complain about the humidity. Their return marks the beginning of an irrevocable revelation to how they’ve engaged with this familiar but still foreign country, which then makes them question whether they’ll ever return again.

The love between the visiting “gringas” and their estranged brother, who is now a parent to a young boy, is undeniable, but there are also unresolved wounds derived from the girls’ privilege of growing up with their father. Dante, who was raised by his grandparents in the DR, feels he was abandoned. A fluctuating dynamic between loving embraces, furious shouting, and a unified reckoning with their shared pasts marks their relationship, and is made more compelling by the believably lived-in bilingual performances from the three leads.

Laden with old photographs and memories galore, the house they’re emptying out is a monument to the family’s history and its roots on the island. Contemplative shots of bare rooms where memories were made and lives were lived give a sense of mournful veneration. This property, a vessel of emotions in decay, doesn’t contain mere objects, but valuable artifacts that carry messages about those who inhabited it. When Rita and Carolina playfully don some of their grandmother’s outfits and wigs, they are, in a way, resurrecting her personality, her stories, and her legacy.

With a succinct screenplay, Peralta avidly executes each scene to offer direct, yet subtle, insight into the divide between the sisters who live abroad and the brother who stayed, as well as powerful indicators that they are more intimately alike than not. This is true especially in a perceptively framed moment where every element functions to bring them together in body and soul.

One afternoon, the two sisters can be seen in the foreground going through old records inside the house. Meanwhile, Dante cleans the garden outside, which we can see in the background through an ornamental iron partition. There’s a separation between them, but as the music begins, the three of them start dancing and eventually come together in a single space.

The song itself also rings with significance: “Compadre Pedro Juan” was popularized by Angel Viloria y su Conjunto Típico Cibaeño, fittingly a merengue band of Dominicans in New York that bridged that gap between the homeland and the diaspora in the 1950s. It’s a track that inadvertently speaks to them about a shared identity and that links them to their grandparents through the music of their youth.

In contrast, a nightclub scene scored with the dembow track “Limonada Coco” by Musicologo The Libro and Lapiz Conciente, paints a picture of young Dominicans today. That song could just as well be playing in a Latino bar in NYC, and elicit a similar reaction. Both music-fueled scenes encapsulate the notion that despite their distinct upbringings and each with their shortcomings, bigger forces connect the siblings. Despite the downbeat truths its clashing protagonists must heartbreakingly wrestle with, there’s a subdued vibrancy in De lo mío.

Repeatedly throughout the sisters’ stay, the camera meditatively looks up at the trees that have been planted on their land for a century, maybe even before their ancestors purchased it. Those trees are witnesses and accomplices to whatever happiness and sorrows unfolded, and Peralta makes their importance known by observing their grandeur unhurriedly. Although unaffected, the visual language in De lo mío has a certain down-to-earth elegance that finds interesting compositions within its disheveled locations, always giving the viewer a moment to focus on a particular wall or a window. Everything is charged with unspoken gravitas.

For Dante, who lives in the country, the physical existence of this building and its surrounding areas doesn’t define who he is. However, the sisters know that when the trees are uprooted so will they, and that loss of something seemingly immovable to ground them there frightens them. Thankfully, it’s in Dante’s son, who meets his aunts for the first time during their trip, that all parties can see a vehicle to remain together, even if apart geographically. The introspective journey Peralta puts Rita and Carolina through is actually not to say goodbye, but to remember that no matter what, the Dominican Republic will always be “de lo suyo.”