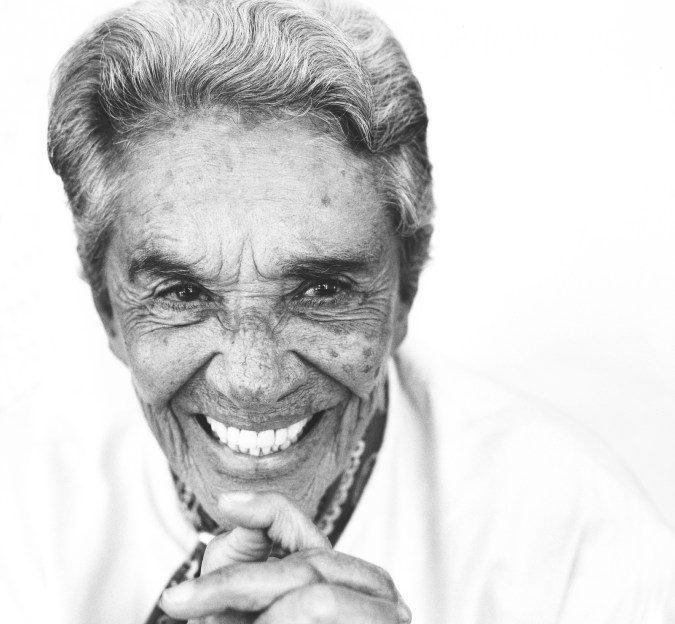

The inimitable Chavela Vargas, the Costa Rican-born godmother of Mexican rancheras, would have turned 98 today, if it weren’t for the respiratory problems that claimed her life on a Sunday in August almost five years ago. Her incomparable contribution to popular music continues to touch generation after generation of artists, Latinx or otherwise. Perhaps unexpectedly for some, one performer who has drawn inspiration from La Chamana is Arca, the visionary Venezuelan producer born Alejandro Ghersi. For him, la gran dama’s influence is invaluable, one that surpasses the confines of musicianship and shapes his worldview as a whole.

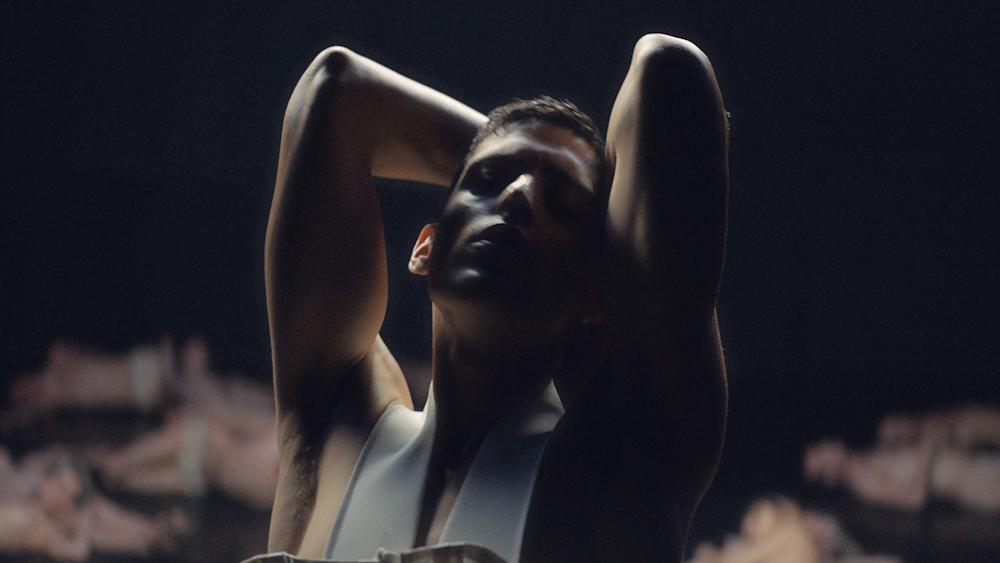

Ghersi just released his self-titled third album through XL Recordings, surprising fans and critics by using his voice more prominently than ever before. The project evinces the undeniable influence that Latin American singers of the past century have had on Ghersi’s melodies and emotive vocal performances. Though the record is steeped in references to Venezuelan folk singer Simón Díaz and the tradition of tonadas llaneras, his idols are many. “Simón Díaz, Caetano Veloso, Mercedes Sosa, Celia Cruz, Chavela Vargas…There have been so many artists from Latin America who weren’t understood through the Western intellectual filter, so people don’t have a fucking clue of how revolutionary their work and lives were,” declares the producer in an interview with Remezcla.

Among these innovators, he cites Chavela Vargas as a peerless influence. “I have a profound connection with the way she existed as a person and as a musician,” he explains. His reverence for la gran dama is distilled most powerfully in Facundo Cabral’s immigrant anthem “No soy de aquí ni soy de allá,” a song she immortalized. “She wasn’t Mexican, but she died Mexican; the Mexican people recognized her as such,” he says about Vargas, who also spent part of her life in her beloved Spain. “There’s a part of me that feels Venezuelan, but there’s another part of me that doesn’t feel Venezuelan.” Although he was born in Caracas, Ghersi split his formative years between South America and the U.S., fleeing Venezuela for New York City after high school. He now resides in London, where much of Arca was recorded. Such cultural collisions speak to the all-too-familiar sense of alienation experienced by children of the diaspora, a reality that has informed the narrative of his new album and his catalogue overall.

Ghersi also draws parallels between his own identity and the way Vargas upended binary expressions of gender and sexuality. “She died a woman, but she didn’t die a woman…There’s a part of me that feels like a man, and there’s another part that doesn’t,” he reveals. “She personified something that still hasn’t been learned. To me, she was genderless, and that was something natural, because in pre-Columbian cultures, the division between masculine and feminine behavior and how it was understood wasn’t as binary. She wasn’t a binary person at all.”

“People look for innovation in the West because it comes naturally for them, and I stand against that.”

La Chamana, who came out as a lesbian at the age of 81, built her career on challenging the conservatism of mid-century Mexican society and excavating a place for women in the male-dominated ranchera world. Vargas wore pants, smoked cigars, and drank tequila without apology – an outrageous thing for a woman to do in 1960s Mexico. Even though the lyrics of the rancheras she interpreted were about heterosexual relationships with women, she refused to change the songs’ feminine pronouns. “The first person who has dared to sing to a woman is me,” she says in Chavela, a new documentary about her life that debuted at this year’s Berlin Film Festival. “I have to say it like it is; I won’t contradict the author or myself, I won’t betray myself.” Likewise, Arca has visually – and now, lyrically – subverted normative expressions of gender since his first album Xen, which he conceptualized around a genderless alter ego who uses feminine pronouns. Ghersi has embraced gender fluidity perhaps most visibly in his live performances and visual collaborations with director Jesse Kanda.

In both of Arca’s Mexico City DJ sets this year, he slipped in Vargas’ wildly popular rendition of “La Llorona,” and accompanied it with a dramatic lip-sync. Together with selections from La Dimensión Latina and Celia Cruz, these tributes to classic Latin American troubadours are more than a testament to the eclecticism of his own musical taste, they are a way of exposing the work of Latinx pioneers to his diverse following. “It’s like, all of these phenomena existed, but then time passes by and people forget how innovative Latinx, Caribbean, Hispanic, or indigenous people have been. People look for innovation in the West because it comes naturally for them, and I stand against that.”

98 years after she was born, Chavela Vargas still burns bright as an iconoclast whose work is reinvented in the oeuvre of artists like Arca. Pop singers, experimentalists, and gender rebels will continue to carry the torch of her unrestrained self-expression, her titanic cultural contributions, and her commitment to resisting normative expressions of queerness in the public sphere.

Arca’s self-titled album is out now via XL Recordings.