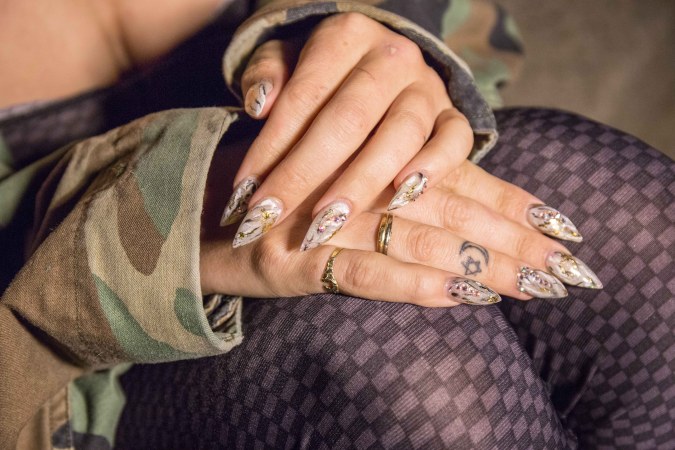

Natalia Garcia radiates confident serenity. The Bay Area singer, who performs as La Favi, speaks low and firm, with aplomb that might seem radically distinct from the featherless reggaeton gospel she’s known for. Her nameplate necklace rests lightly on her chest, and as she speaks, her crystalline manicure, encrusted with miniature rhinestones and golden flecks, shimmers in the fading light. It’s a dusky November evening right after the 2016 presidential election, and we’re discussing the politicization of music in the Trump era. “I was raised around people that mentored me and were organizers in the movement, so cuando a mi me llaman, I’ll be there. But sometimes, I think there’s a lot of power in coming together just to soltar un poco la pena. Sometimes those simple things are more powerful than people care to understand.”

That philosophy of catharsis floods Reir y Llorar, La Favi’s new EP, unveiled today via Terror Negro Records. The six-song collection evinces reggaeton’s breakneck dash into new directions; it opens the pages of the genre’s textbook and rips convention to shreds. On the soaring opener “Tu y Yo,” La Favi coos over a forlorn trap instrumental that shapeshifts into a dembow riddim. The EP is packed with laments about the ecstasy of short-lived dance floor romances, unrequited love, and maudlin solitude. They’re indulgently morose protection spells that herald the dawn of sad girl reggaeton.

La Favi recalls studio sessions with Terror Negro head honcho Deltatron, who produced the EP. “He was like, ‘Tu eres la llorona,” she laughs. “I feel super blessed and lucky just to be able to do what I do. But it’s definitely been my outlet…I definitely had to do it for the sad girls.”

“I definitely had to do it for the sad girls.”

The airy melancholy of Reir y Llorar is likely the fruit of Natalia’s eclectic musical upbringing. The singer grew up in a Chicanx and Central American community of San Francisco, on balladeers and troubadours like Selena and Ivy Queen. As the grandchild of Spanish Civil War refugees from Andalusia, Natalia found nourishment in classic flamenco records she heard at home and on trips back to Almería, the coastal city her family hails from. On Reir y Llorar, her cante jondo falsettos flutter around sinister hi hats and dembow kick drums, prancing between trap and reggaeton and back again. She admits the vocal style emerges in her music more out of admiration than formal training. “It’s definitely more imitando than really doing it like puro, puro flamenco. I love flamenco; it definitely shapes me, but I think it’s one of those things that, como que se lleva en la sangre, and you grow up doing it.”

But the journey to embrace that tradition wasn’t necessarily seamless. “When I first started recording, some of the people that were recording me were like, ‘You need to calm that down. Don’t do that; don’t do that with your voice.'” But her cante jondo vocalizations ache with beauty on Reir y Llorar, in a way that echoes the subversive creative promise the genre has always borne. It arises in unexpected moments, like the aquatic palate cleanser “Nai No Nai,” or the posse cut “Lluvia,” featuring Tumblr star Ms Nina and tattoo artist Tomasa del Real. It betrays what scholar Petra R. Rivera-Rideau once said: “The history of reggaeton is one of transformation.” From the proto-perreo of El General, to the rabid, maximalist barking of Daddy Yankee, the song form has continuously served as a canvas for experimentation, a promise amplified by its mainstream success and the advent of the internet.

“I can’t claim to represent reggaeton. I feel like I’m a guest.”

La Favi is perhaps most widely known for her verse on Los Rakas’ 2011 hit “Abrazame,” but in the past year, she’s emerged as a scion of the reggaeton reinas who once commanded the genre. Along with Ms Nina and Tomasa del Real, La Favi joins a new cadre of women honoring the genre’s bad girl roots, each bringing their own insurgent vision to a scene built on Facebook chat and SoundCloud. While Tomasa del Real and Ms Nina’s tough-talk machinations savor the playfully debaucherous, La Favi is softer than her peers, more pensive and somber.

Garcia is shrewdly aware of the messy respectability politics thrust on the women of reggaeton since Day 1, when the breathless moans of Glory or Jenny la Sexy Voz were not only controversial, but banned on local radio. It’s a tangled reputation she must contend with even 25 years after the genre’s inception. “It’s [considered] shameful for the family – to be out there and to be showing your body or dancing in public and speaking on certain things,” she says.

For her, it’s a pernicious strain of sexism that dissuades many young reggaetoneras from pursuing creative careers in the genre. “They don’t really have the freedom, because you’re kind of bound by your family; you want to be safe,” she explains. “Even if you just put a picture of yourself on Facebook, anyone from your tía to the niño rata in his house will be like, ‘Puta!’ You learn to deal with it and defend yourself and protect yourself.”

It’s an all-too-familiar reality for any woman in the urbano industry. Decades after the genre coalesced in Santurce’s caseríos, critics continue to bicker over whether reggaeton is an exploitative or empowering space for them. But La Favi notes that its originators always celebrated resistance. “Ever since the beginning – especially the strong Afro-Latina, Afro-Indigenous women – have been putting these messages out. Ivy Queen, that was one of the first inspirations,” she recalls, humming a flamenco take on “Quiero Bailar.”

The influence of stereotype-defying icons like Ivy Queen is inscribed all over Garcia’s music. Her songs harken back to the genre’s halcyon days, when La Caballota snatched women’s pleasure out of reggaetoneros’ hands and served it to herself on a platter. Likewise, La Favi’s compositions function like baboso antidotes. Take “No Eres Bueno,” a song she quietly released on SoundCloud in 2016: “Aunque todos dicen que te debo de dejar/irme con otro que me sepa cuidar/pero no me voy a alejar/aunque yo quisiera no pudiera olvidar.”

On Reir y Llorar‘s “Controla,” a plaintive violin and piano serve as a reminder of why you should stay away from the broke bois you can’t seem to quit. “Nunca ando sola/me llaman a toda hora/disparo de pistola/tu ya no me controla,” she spits with rancorous gloom. It’s a reminder that reggaeton has always been a site of resistance, a street sound whose perennial promise was one of rebellion – a space to be raunchy, to be candid, to be free.

“I can’t claim to represent reggaeton. I feel like I’m a guest,” she reminds me, reflecting on her place in the movement. As reggaeton continues to be reimagined by genre rebels across the Latinx diaspora, escaping the hyperlocal spaces it once operated in, La Favi’s gratitude for its source material is vital. The sound’s future seems predicated on the safeguarding of its defiant origins, where the categories of race, gender, class and the underground were disrupted by Panamanian, Afro-Puerto Rican, and barrio innovators. “I can be a guest, and I can work with people. I feel so lucky to do that, that I’ve been able to be in the Caribe o en Mexico, que la gente me enseña muchos amores,” she adds. It’s only with knowledge of that conflict that we can envision longevity for the genre. “No salió de nada. Music comes out of people’s pain and struggle.”