Latinxs are more visible in American hip-hop than ever before, but yet still so obscured. Despite being part of this music from the very beginning, from the first Kool Herc party in the Bronx, Latinxs are still treated as second-class citizens in a genre we not only helped birth but have participated in as artists, managers, label team members and listeners. Latinz Goin Platinum is here to highlight our successes, past and present, as we build towards rap’s future, uncovering histories hidden in plain sight and identifying the Latinxs currently active in hip-hop.

“Everybody’s checkin’ for Pun, second to none

‘Cause Latins goin’ platinum was destined to come.”

-Big Pun, “You Came Up” (1998)

The story of hip-hop has many touch points, as would any tale that spans nearly five decades. But as we know from the cinematic universes of Star Wars, Marvel Comics and Chespirito, every saga has a beginning—and this one starts in The Bronx.

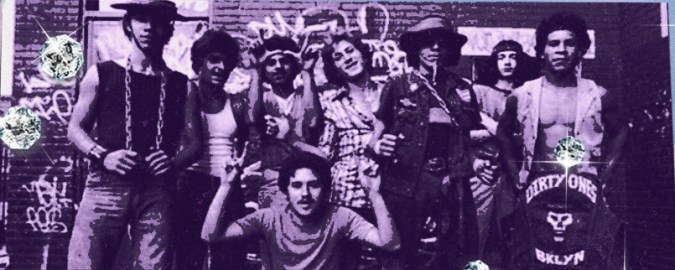

By 1971, gangs ran rampant in the borough, its ranks populated almost entirely by African-Americans and Latinxs, representative of the then-contemporary demographics. In the previous decade, New York City’s upper reaches had undergone extraordinary change, with white flight and community-wrecking endeavors like the Cross Bronx Expressway causing untold damage to the immigrants and residents of color that remained. Amid the urban decay, Black and brown teens and twenty-somethings joined gangs out of necessity. Movement was limited as a result of increased territoriality, which further limited economic opportunities than they already were.

Violence and the threat of it had become a part of daily life. Some “clubs” saw themselves as righteously protective of their turf, while others were simply sworn to defend it by any means necessary. Several at the time like the Savage Nomads and the Savage Skulls adopted Nazi symbols and hierarchical ranks as part of their aesthetic, not to align with or subvert the history of said imagery but instead to elicit fear and demonstrate might. In truth, they needn’t have bothered, since they would have done a fine job of terrorizing their neighbors and provoking their rivals without all that.

The organized rumbles of the 1950s were no longer in play, with the likelihood of death a far greater outcome than in the past. Such a fate befell Cornell “Black Benjie” Benjamin of the Ghetto Brothers, a prominent South Bronx set that espoused Puerto Rican nationalism as part of its ethos. On December 2, 1971, during a particularly intense spate of bloody inter-gang violence affecting numerous neighborhoods and establishments, Benjamin was beaten and fatally stabbed while attempting mediation between rival clubs.

Over the ensuing years leading to what we know as the genre’s storied Golden Age, Latinxs played crucial roles in hip-hop on the mic, as DJs, in the studio and on the business side.

Given his stature, it proved a turning point that paved the way for the cultural movement we call hip-hop. On December 8, less than a week after Benjamin’s death, an unprecedented gathering took place in the Bronx at the Boys Club on Hoe Avenue. Representatives from more than three dozen clubs, many of whom were Dominican or Puerto Rican, met there in the interest of peace and preservation—their efforts culminating in a truce. While it certainly didn’t put an end to gang violence uptown, the historic event eased tensions and brought unity in ways no outside party could have.

Many cite DJ Kool Herc’s August 1973 “Back To School Jam” party as the official birthdate of hip-hop, but the genre’s conception happened nearly two years earlier. Herc’s seminal celebration could not have been held if not for what became known as the Hoe Avenue Peace Meeting. The agreement made it possible for African-American, Afro-Caribbean and other Latinx members of these groups to congregate amicably together to enjoy the music and the company.

Those who witnessed Kool Herc’s technique live at the game-changing Back To School Jam and later such events saw the possibilities. Among those present at a party held at the Police Athletic League on 183rd Street in the Bronx was Luis Cedeño. A half Cuban half Puerto Rican kid from the borough, he took on DJing with the encouragement and cooperation of his friend Curtis Fischer, better known to hip-hop fans as Grandmaster Caz. By the mid-1970s, Cedeño had adopted the moniker Disco Wiz and effectively became the first Latinx DJ in the emerging genre with his childhood pal in their Mighty Force crew.

As detailed in his book It’s Just Begun: The Epic Journey Of DJ Disco Wiz, his career was abruptly interrupted by an attempted murder charge in 1978. He spent four and a half years serving time, which meant he missed the pivotal period at the turn of the 1980s in which hip-hop saw its first hit singles. Before his incarceration, he’d played the same P.A.L. that Kool Herc did; afterwards, he stayed away from music for some time. That tragic circumstance helps to explain why the name DJ Disco Wiz isn’t as widely known as he deserves to be, another obscuring of Latinx participation in the genre’s early history.

While this period precedes recorded hip-hop, it happens to coincide with the genesis of some of the first Latinx rappers to come from uptown. Yes, Big Pun and Fat Joe were still toddlers in 1973, growing up in the South Bronx amid this nascent cultural movement. But Prince Whipper Whip, born in 1962, split his Nuyorican youth between the borough of his birth and the island of his forefathers, an experience many of his generation and later ones can relate to. An O.G. member of the legendary Cold Crush Brothers and also affiliated with Mighty Force for a time, he subsequently joined up with Grandwizard Theodore as part of the Fantastic Five, his ethnicity seemingly immortalized in the opening lyrics to their classic “Can I Get A Soul Clapp”:

“We’re fresh out the pack

So you gotta stay back

We got one Puerto Rican

And the rest are Black”

That lyric, however, was somewhat misleading, as it referred not to Whipper Whip but fellow rapper Ruby Dee, who was born Rubin Garcia in Puerto Rico and subsequently lived in Harlem before moving in 1977 to the Bronx. His verse follows Whip’s, and explicitly details his identity:

“Ruby Dee is my name and I’m a Puerto Rican

You might think I’m Black by the way that I’m speakin'”

Over the ensuing years leading to what we know as the genre’s storied Golden Age, Latinxs played crucial roles in hip-hop on the mic, as DJs, in the studio and on the business side. Their backgrounds were evident in varying degrees, complicating matters nowadays as some seek to treat their presence as somehow marginal or secondary. But from the Hoe Avenue meeting onwards, the influence of Latinxs was fundamental and foundational, forever inextricably linked to this music, as part of our urban Latin thing.