Colombian illustrator Rapiña has collected more than 1,800 zines in the last decade or so. More than 10 years ago, she began by collecting a handful of zines from artists that defined an era: the Cali-based collective Sursystem, the irreverent Inu Waters, and the provocative Andres “Frix” Bustamante. Set against a backdrop of an armed conflict and rampant inequality, these zines offered a lifeline for a new generation wary of the mediatic echo chamber and “business as usual” politics.

When the zine frenzy arrived four decades ago in Latin America, it stirred up much of the same sentiment it had in the United States. Artists, writers, and conscious thinkers who had never found themselves reflected on TV screens or the daily paper found self-publishing to be an innovative way to spread their ideas. Captured in these DIY magazines were the manifestations of anti-fascist punks, feminist activists, and anarchist creatives.

“What’s important about the zine is that it informs us of a culture that’s happening all around us, but that we don’t see in libraries or bookstores.”

“Zines reflect all the dynamics happening in that moment in a country, be they cultural, economic, political, or religious,” Rapiña tells me. “What’s important about the zine is that it informs us of a culture that’s happening all around us, but that we don’t see in libraries or bookstores.”

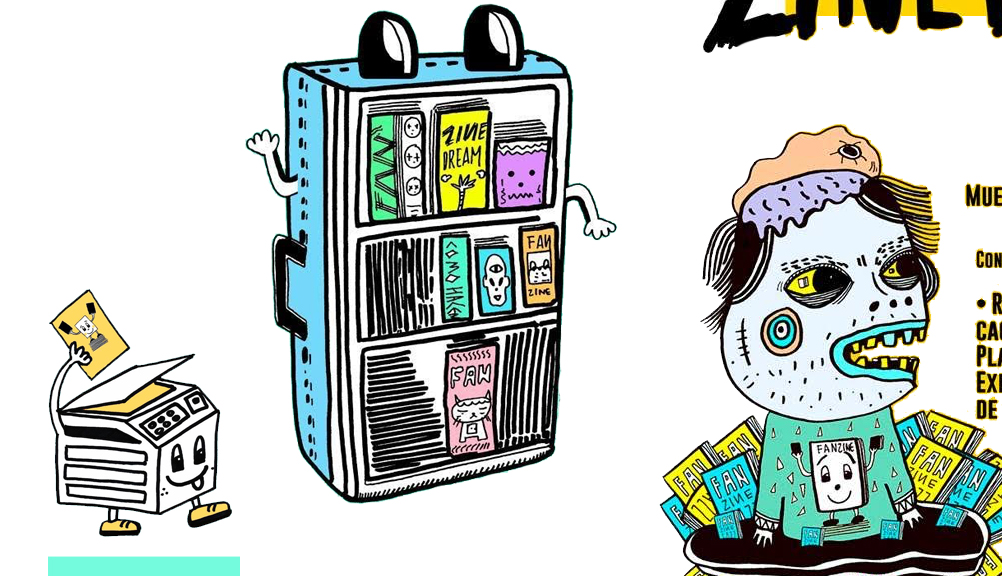

Over the years, what was once a pile of zines Rapiña had casually collected expanded into an extensive archive that had gained serious recognition. In 2016 – when Rapiña was invited to an exhibit uniting the works of Colombian and Peruvian zinesters in Bogotá and Lima – she founded La Maleta Fanzinera, a massive archive that aims to preserve zines from across Latin America and to showcase them in a traveling exhibit. So far, this project has amassed nearly 2,000 publications from Colombia, Peru, Chile, Argentina, and other countries and continues to grow as Rapiña travels the continent collecting zines and accepting donations from fellow zine aficionados.

Despite their historical value, zines often fade into obscurity. Sometimes zine series are discontinued and forgotten or sometimes collectors lose interest in their haul and discard them. In recent years, a shift in perception of the zine as a valid form of expression has influenced institutions such as national archives and libraries to preserve these cultural artifacts. Their work is crucial, Rapiña recognizes, but what distinguishes La Maleta Fanzinera from other archives is the accessibility of the material for the average person.

“Other archives are stored, kept in only one space where people have people have to go to look at them. If they’re friends with certain zine makers, they can access the archive, but it’s not easy. The difference with our archive is that we take the zines to the people,” Rapiña explains.

Any given exhibit of La Maleta Fanzinera can showcase up to 300 zines that are curated to suit the theme of the event. Rapiña travels with a suitcase full of zines in hand to various festivals in cities across Colombia and countries such as Argentina and Peru, but she has also makes sure to exhibit in smaller events with the intention of always reaching a new audience. Local zinesters are also welcome to arrive at any Maleta Fanzinera booth with their DIY works to donate to the project. These zines are displayed in the following exhibits and later catalogued in Rapiña’s home in the outskirts of Bogota, where they continue to live on in her archive.

Keeping up with an archive of zines – some of them dating back to 2007 – is tough. Properly preserving the materials means storing the zines in paper slips that prevent the ink from fading, Rapiña said, but high costs impede for her doing so. For now, she keeps the zines protected in cardboard boxes, away from light. She also keeps two copies of every zine collected after the heat at a fateful exhibit warped a selection of zines.

Still, Rapiña sees the collection and sharing of these cultural productions worth all of the effort. Zines are the non-official record of history, as Rapiña sees it. They not only preserve the aesthetics of a place in time, but can also be the only lasting remnants of a social, political, or cultural movement. As the popularity of zines resurges in Latin America, Rapiña sees an opportunity for Latin American zine makers, festival organizers, and archivists to learn about and build what she calls the “B-side” of history.

“These projects are so important because all this knowledge shouldn’t remain in one country.”

Ariadna Varse, a Mexican transplant in Ecuador, is one of the many fanzineras included in Rapiña’s roving library and is fueling a countercultural movement planted in transfeminist and anti-capitalist ideals. Varse sees the zine as a space where women can collaborate and display their work without the constraints of traditional publications and where seeds of resistance can sprout. Projects like La Maleta Fanzinera and ones she has helped co-found such as La Cachina Fest and Runa Microeditorial, Varse argues, only help nourish a sense of community among zine makers in Latin America that is increasingly growing.

“These projects are so important because all this knowledge shouldn’t remain in one country,” Varse says. “In this exchange of ideas, you begin to understand what the context in their country is like, what processes are underway, what is their reality. For me, Latin America is united and powerful.”