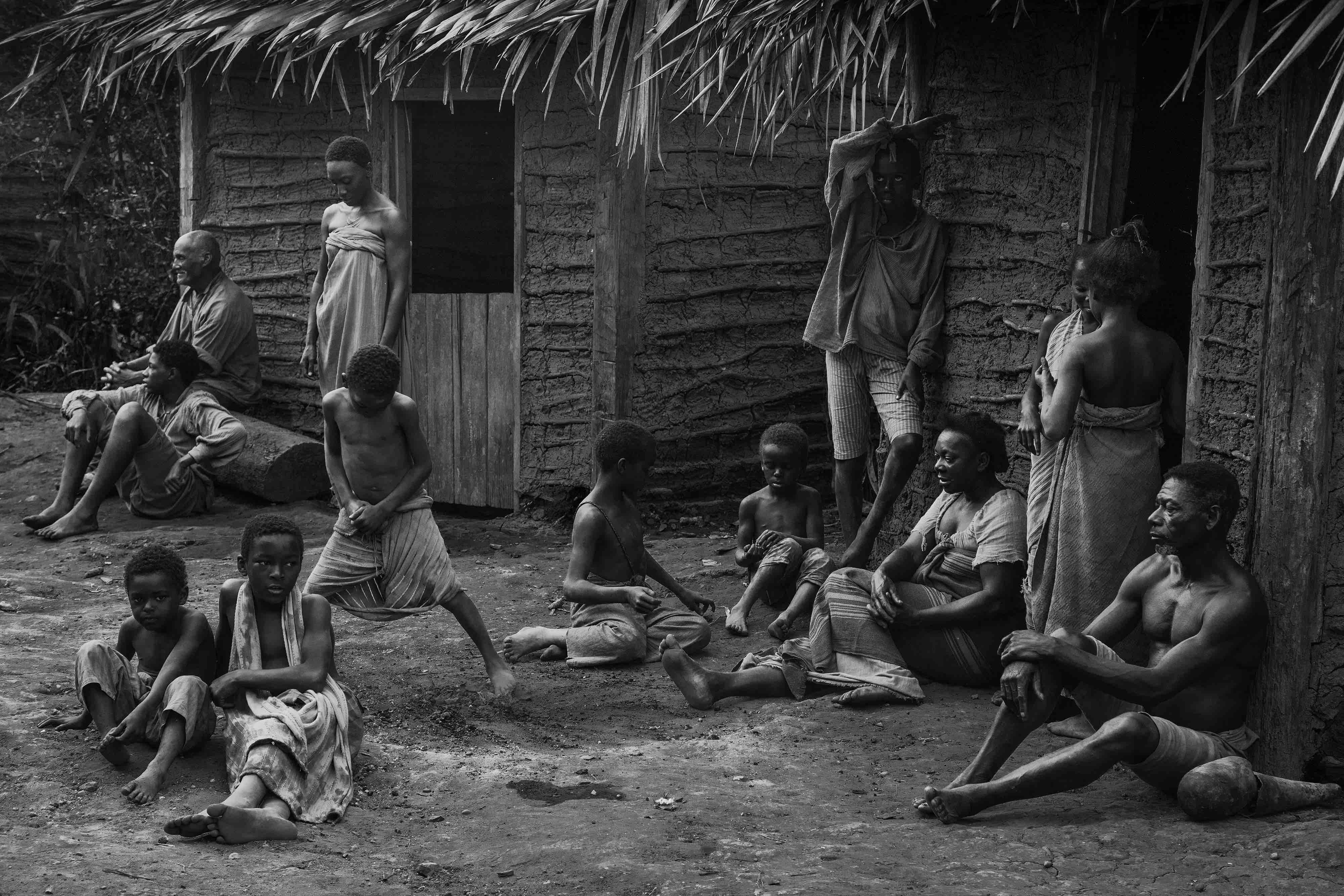

Set in 1821 – a year before Brazil declared its independence from Portugal – director Daniela Thomas’ first solo effort, Vazante, is an ambitious and atmospheric period film that digs into the country’s brutal past dominated by white males. Rendered in breathtaking black-and-white cinematography, this tale centered on the commonplace horrors of slavery at the time and the objectification of women of any race, was inspired by a disturbing passage in Thomas’ family history and her love for Graciliano Ramos’ movie Vidas Secas (Barren Lives).

That 1960s film dealt with “the difficulties of people that have no education and who have no knowledge of language to convey their emotions, or to even understand what they are feeling because they cannot name it.” Thomas captures this sentiment through silences, astonishing landscapes, fearless close-ups, and a collection of communal moments between the slaves trapped in the infuriating tragedy of their circumstances.

Shockingly, considering what making a historical drama entails, the project’s budget was only $2 million. Thomas wanted to push forward the conversation about the origins of racism in Brazil, one that is often excluded from the big screen, and to confront viewers with the casual brutality of a system fueled by subjugation. In Vazante, Antonio (Adriano Carvalho), a drover and slave-owner, forces his deceased wife’s family to give him their young daughter to marry her – a tyrannical move that sets the audacious plot in motion.

In a conversation with Remezcla, Daniela Thomas shared her insightful and cutting opinions about Brazil, the negative side of working with Walter Sallas, and being impressed by Lucrecia Martel’s Zama.

On Brazilian Cinema Avoiding the Country’s Past

“That was the first impulse, to make a film that had never been done before in Brazilian film culture.”

Films, for me, are like testaments, a witness account, a historical account of life in a place and in a time. The cinema of Brazil has somehow evaded the history of our country. We don’t have an image of the past. Usually, our cinema has an image of the past that is related to oneiric, symbolic, or carnival-like expressions of the past.

Instead of doing that, I tried to be very faithful and I felt we needed that in our cinema. That was the first impulse, to make a film that had never been done before in Brazilian film culture. This was the first impulsive, but also, it was based on a personal story, a story in my family, family lore. It was a story my father told about this great-great-uncle who had married a 12-year-old girl, which was a normal thing in the past. He waited three years for her to menstruate before he consummated his marriage. He used to bring her dolls and treated her like a child, which I found all very perverse and it somehow echoed with the amount of perversity that still is acceptable in Brazil in the government, in relationships, and in so many things. That’s the origin of Vazante.

On Injustice in Brazil and the Slavery Enterprise at Its Root

Brazil is one of the most unjust countries in the world, with the biggest distance between the poor and the rich. We have to confront this. We have to try to understand where this comes from: the racism and the injustice. I studied history. My first major was history, so there is a very old desire in me to understand where it comes from. We have to understand that slavery was something that was imposed. It was an economic enterprise, as well as the enslavement on indigenous people. It was all about economics.

This is the way Brazil was colonized, as an enterprise, exploiting nature and exploiting humans, and maintaining this structure or system in which the white male has all the power. But what is interesting about the film, I hope, is that at the same time it does not talk about flat people. We are talking about humans, caught in this crazy pact. That’s what I like about the work that we did, is to try and humanize even the monsters, the people who are in a monstrous position to which the system has brought them. I had interest in humanizing and trying to portray the complexity of relationships in this situation.

“There is a very intense focus on the erotic, sadistic, display of violence against the black skin in American films about slavery.”

On the Difference Between Vazante and American Films About Slavery

I think what is most different, I hope, is the fact that I think there is a tradition, almost like a genre, of slave films in America, even exploitation movies from the ’70s. There is a very intense focus on the erotic, sadistic, display of violence against the black skin in American films about slavery, even in something like 12 Years a Slave. There is an obsession with the torture as if slavery is like a personal, sadomasochistic experiment for a psychopathic white man. I really tried to escape that. I wanted to talk about the banality of evil. There is a concept by a philosopher called Hannah Arendt, which says evil can be banal. It can be ingrained in every relationship without people even noticing how evil it can be.

I didn’t want to explore the torture, but to talk about how terrible it is when you based a whole life on the exploitation of a human being by another, on the use of a human being by another. I’m talking about not just race, but also men, women, or children. Nothing good can come out it. When evil is banal it’s hard to recognize it and you start to think this is normality, when it’s nothing but abnormality. When evil is everywhere, you think it’s normal, so you accept it and you live within a very terrible structure: When a child can be married at 12, or when a woman can be used as a sex toy whenever a man wants because he owns her.

On Making the Film Black-and-White

I love black-and-white. My first feature was black-and-white. I’m a fan of the intensity of emotion in it, and I’m also a lover of landscape as a form of communication in cinema. Cinema is the best medium to convey landscape, and I think that at that time landscape was a great part of life because you lived in the landscape. I also thought black-and-white is a symbiotic trick to get people immediately into the past. There is a unique quality about black-and-white photography. In Brazil, we have very strong black-and-white photography. There is an important photographer who did a lot of photography of ex-slaves in Brazil. We have a lot of information in black-and-white and we have very little information in color. In Brazil, we don’t have a museum of old master Brazilian paintings. We don’t have an image of the color of our past. I didn’t want to work with all the possibilities, with the unknown, so I thought black-and-white would help me not to have to make decisions about which way things looked back then. I would be guessing. We don’t have enough information.

On the Whiteness of Latin American Cinema

Latin America, in cinema, is a white continent, isn’t it? It’s incredibly white. It has to change. 400 years of slavery is not a joke. There was a dramatic movement of human beings around the world. Their culture and the things that they have done for the economies and for societies of the world have to be told. I just saw a film by Lucrecia Martel, Zama, and it was the first time I’ve seen black people in Argentine cinema. It’s actually a Brazilian actress who plays the black slave in Zama, but she doesn’t talk. Still, I loved the film. She is one of my favorite directors in the whole world.

“There is that idea that somehow a woman in a partnership is secondary … and not an equal partner.”

On Her Name Being Omitted in the Press When She Co-Directed with Walter Sallas

I was brought in a family where the idea of me being a woman and it making a difference in my ambition or personal expression had no power whatsoever. I was brought to fight and be whatever I wished and I hoped to be. But I have suffered some things. For example, I did a lot of films in partnership with another director, Walter Sallas, and in many occasions my name was not written in articles or even in encyclopedias of cinema. There is that idea that somehow a woman in a partnership is secondary, the subservient, the assistant, so to speak, and not an equal partner. That I have really suffered a lot throughout the years I made films with Walter, but here they couldn’t do that because there was nobody else. This didn’t discourage [me] from working in a partnership, but what I really wanted was to chase my own questions. Partnerships are always negotiated. I love Walter, he is my teacher, but you have to find your voice. It was time. I’m 58 now. It was time that I got out of the egg and did my film, which I’m happy to have done.

On the Casting Descendants of Slaves and African Refugees

I only knew I could make the film when I found black people that are the descendants of the slaves who live specifically in the area where I filmed. I found them through a documentary about the Quilombo communities. Quilombos are runaway slaves communities. When I found them I realized I could make the film. Some of them were descendants of the slaves from that very farm. Isn’t that incredible? It was a very long casting process. Similarly, the black actors that played slaves that just came from Africa are actually African people that have just come to Brazil as refugees from Mali or Burkina. They don’t speak a word of Portuguese. I really wanted to create a true laboratory of the experiences of many people from many parts of the world living together very far away from any villages or cities that existed at that time.

On Why She Thinks Criticisms Towards the Film Has Been Positive for Brazil

There was a big controversy because there wasn’t a single film in Brazil last year that created asmuch press as Vazante, but not exactly for the best reasons. The black community of Brazil, particularly the one related to film criticism, was really unhappy with the lack of protagonism of the black characters in the film. They said it was a very conservative way of telling the history of the past. The film was questioned for its portrayal of the black population. There were very, very intense discussions. It was very polarized and it was very interesting. I was very uncomfortable, but I was also very happy at the same time, because all the cultural publications were talking about the question of racism and the black community’s fight. I felt very proud that I brought this discussion to the media.

On the World’s Fight for Change

Brazil is a nation that was born of rape. Brazil is a very misogynistic country, but we are in the midst of a worldwide important moment in the recognition of different identities and minorities. It’s not just in Brazil. It’s everywhere, even in the Arab countries. There is a big struggle going on. I think men have been taken aback by the sudden change in the normality. What was considered normal now is being questioned everywhere. In Brazil, we have a very bad past. The way we were constituted was very difficult, very patriarchal, very empowering of the white male. We have a long way to go, but we are fighting.

Vazante opens in New York on January 12 and in Los Angeles on January 26.