Locked away in a bathroom at La Casa Azul, the Mexico City home-turned-museum of Frida Kahlo, stacks of thousands of portraits were discovered in 2004, more than 50 years after her death. The images are providing art scholars and aficionados a glimpse of the ways photography informed Kahlo’s own paintings as well as her lionized self-constructed image.

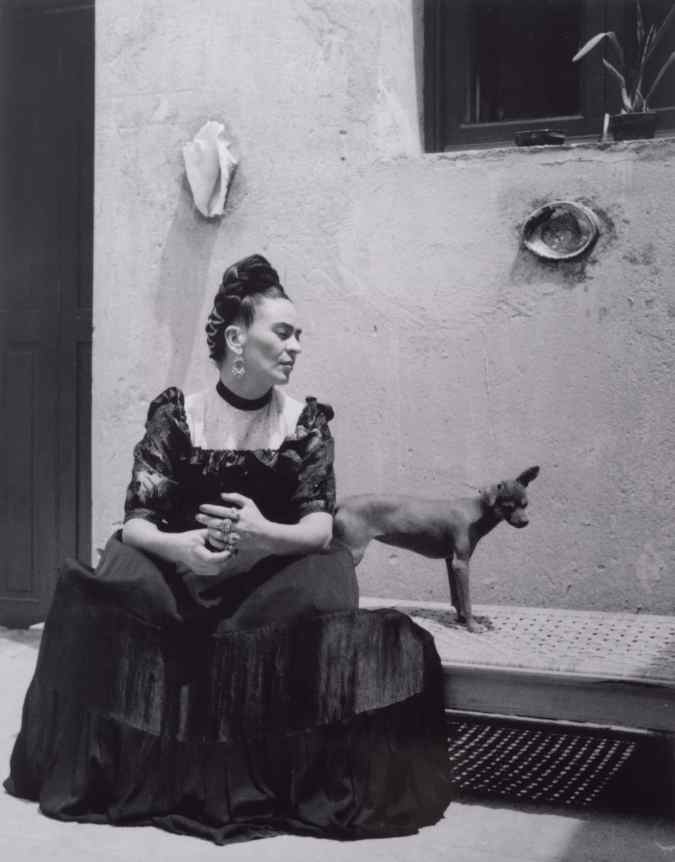

Among the 6,500 archives found – a selection of them currently on display at the Brooklyn Museum’s Frida Kahlo: Appearances Can Be Deceiving exhibition – were her most-famous self portraits, photos of lovers, friends, family and pets, and the works of her father, Guillermo Kahlo.

Born in 1871 in Pforzheim, Germany, her dad, Carl Wilhelm Kahlo, moved to Mexico when he was 19, where he changed his name to Guillermo. There, he was an apprentice to a studio photographer. After the death of his first wife, he married his boss’s daughter, Matilde Calderón, who encouraged him to pursue photography as well. It didn’t take long for Guillermo to gain fame throughout the country, becoming known for his images of landscapes, buildings and interiors. In 1901, he opened his own photographic studio in Mexico City and picked up a profitable commission from former Mexican President Porfirio Díaz to photograph the country’s colonial heritage. That same year, he published his 25-volume portfolio of churches, factories and convents.

By the time Frida, who was Guillermo and Matilde’s third daughter, was born in 1907, her father was already a celebrated photographer. Much of her childhood was spent at his side, helping him in his dark room and accompanying him on photographic assignments. From Guillermo, she learned the technical details of his profession, like how to operate a camera, develop film, print photos and tint images, as well as the artistic aspects. In fact, one of Frida’s earliest paintings illustrated the sun-baked dome of a cathedral in a city that looked a lot like a child’s portrayal of her father’s own photography.

Guillermo also taught Frida, who he described as his “most intelligent” daughter and the one who was most like him, about staging and composition – lessons that would influence her popular self-portraits in the years that followed.

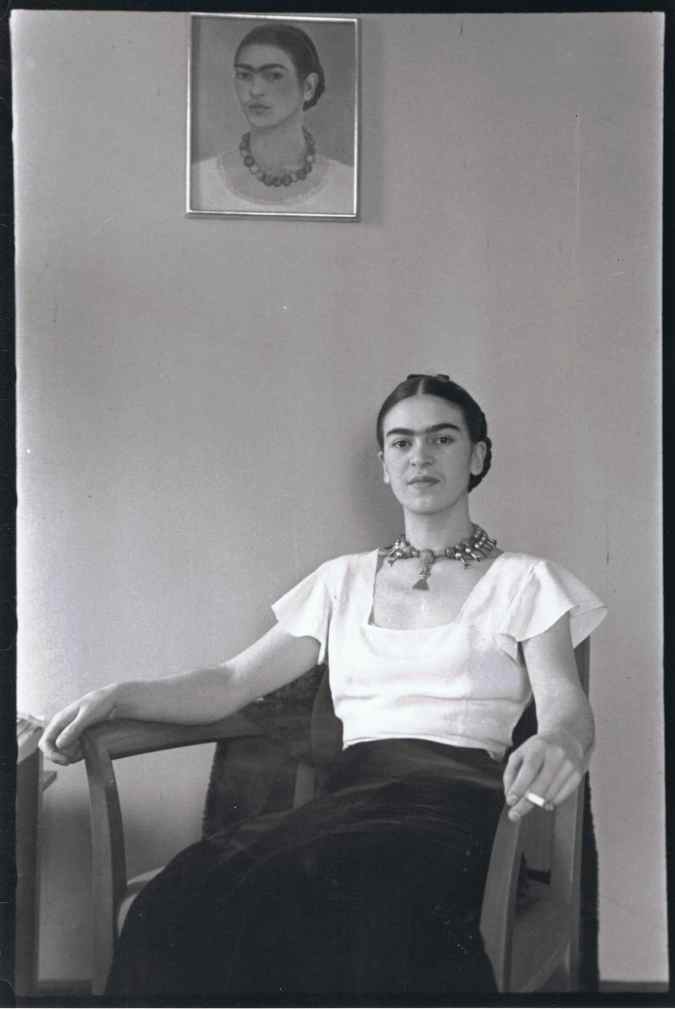

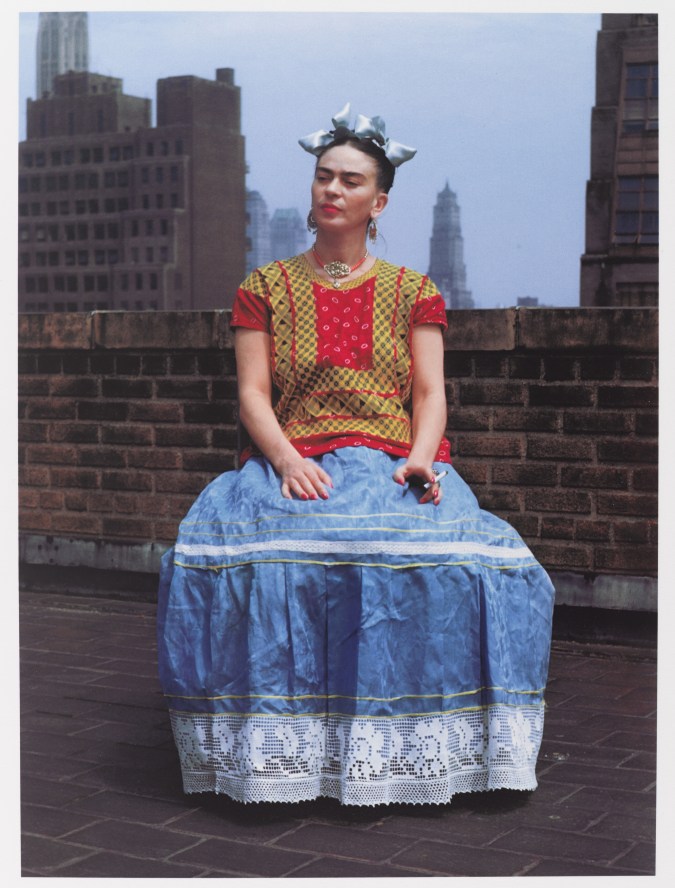

“From a very young age, Kahlo learned to pose for the camera, often gazing straight at the camera with her characteristic defiance. This awareness of the onlooker, through the eye of the camera, but also of her own reflection, marks the beginning of her self-made image,” Baeza Ruiz, a researcher from the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, which held an exhibition of Kahlo’s recently discovered belongings in 2018, told DW.

In a portrait by Guillermo taken in 1919, when Frida was 11 years old, she’s seen wearing an oversized hair bow and dress, giving the lens an intense gaze that is prominent in her own future artworks. Five years later, he photographs Frida in a family photo; her stern look present, though her girlish garbs are replaced with a man’s three-piece suit, likely belonging to her father, that hints to a reshaping of self through clothes, another practice she’d later adopt in her paintings.

While Guillermo hoped his daughter would take after him and become a photographer, as an artist, she was still able to channel his work. After an accident in 1925 left her bedridden in a plaster corset for months, she began painting self-portraits from a mirror. Her paintings, which presented her stiff and austere, were directly inspired by her father’s work. She appeared, as she described in her own words, “unflinching, unsmiling, determined to show that I was a good fighter to the end.” Later, in an unfinished drawing that attempted to capture herself in different stages of her life, she even sketched the silhouettes of three portraits, two taken by her father between 1913 and 1926.

“Kahlo captures here the transition from childhood to early youth, showing her fascination with her self-made image, but she is also tracing her relationship with the camera, her father and the viewer,” Ruiz said.

The influence of Frida’s father’s work on her own art wasn’t lost on her – it was intentional. She once compared her paintings to his photos, saying Guillermo painted the outer reality, while she painted the interior world. Still, Frida’s greatest nod to her father was undoubtedly her painting, Portrait of my Father. The piece shows her dad, then deceased for 10 years, glancing to the side with his camera behind him, “emphasizing his trade as both intellectual and technical labor,” says Ruiz.

While Guillermo was undoubtedly the most important photographer in Frida’s life, he wasn’t the only one. The artist was close friends with Depression-era documentary photographer Dorothea Lange, bonding over a shared experience with polio, adulterous spouses, and photography. Even more, throughout her career, Frida’s stony gaze, iconic unibrow and long, colorful floral skirts made her “an irresistible subject for portraiture.” She was photographed by early 20th century masters of the lens, like Edward Weston, who once wrote that Frida “[was] a little doll alongside Diego … People stopped to look in wonder,” as well as Imogen Cunningham, Martin Munkacsi and Lola Álvarez Bravo. However, her most intimate and popular portraits, including the vibrant Frida on White Bench and a partially nude piece of the artist lying down, were taken by her lover, Hungarian-born photographer Nickolas Muray.

Some of these portraits, including pieces taken by Guillermo and Muray, are on display at Frida Kahlo: Appearances Can Be Deceiving alongside hundreds of other personal possessions and rediscovered clothing items that had been locked away for decades. The exhibition, the largest in the country devoted to the iconic painter in the last 10 years, runs at the Brooklyn Museum until May 12, 2019.