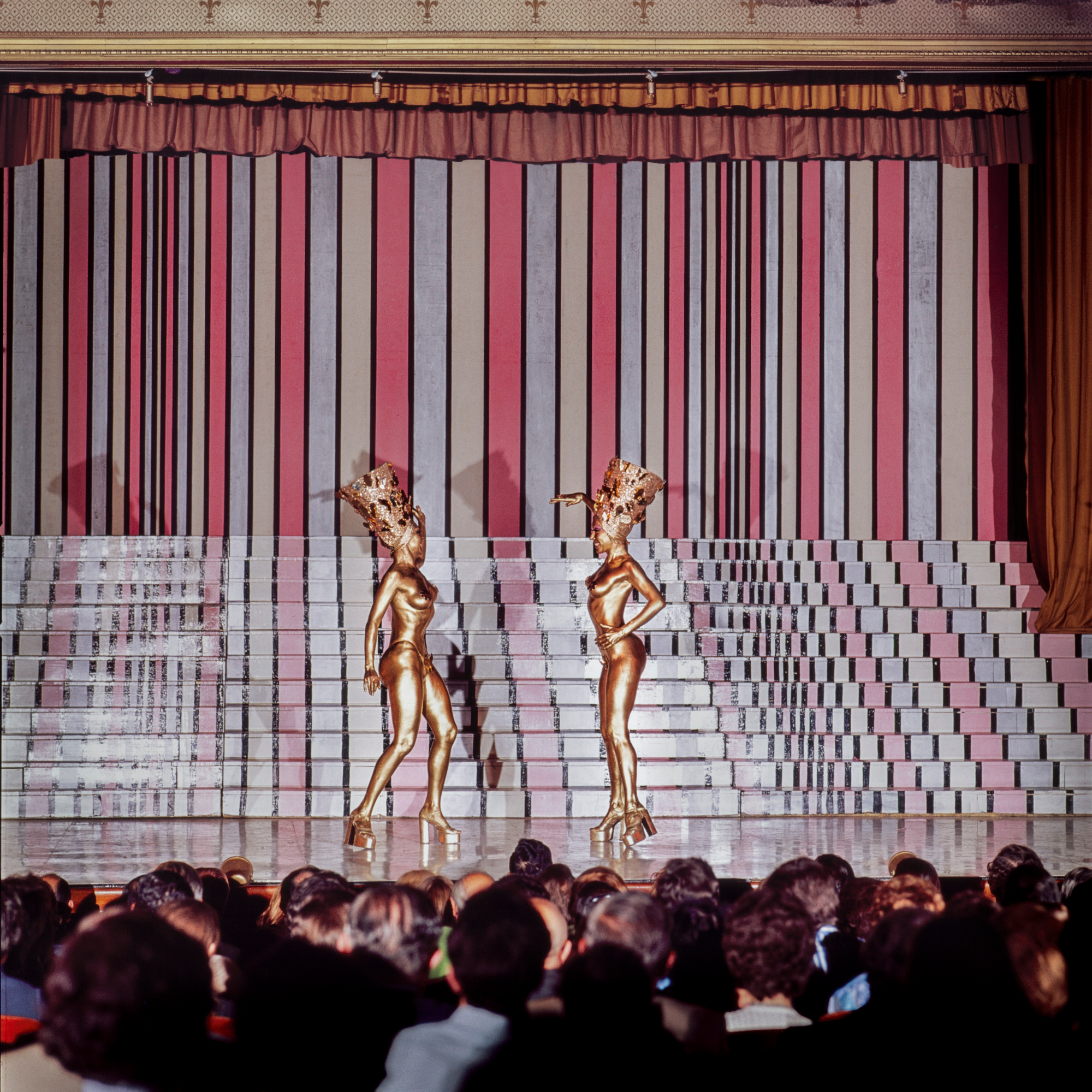

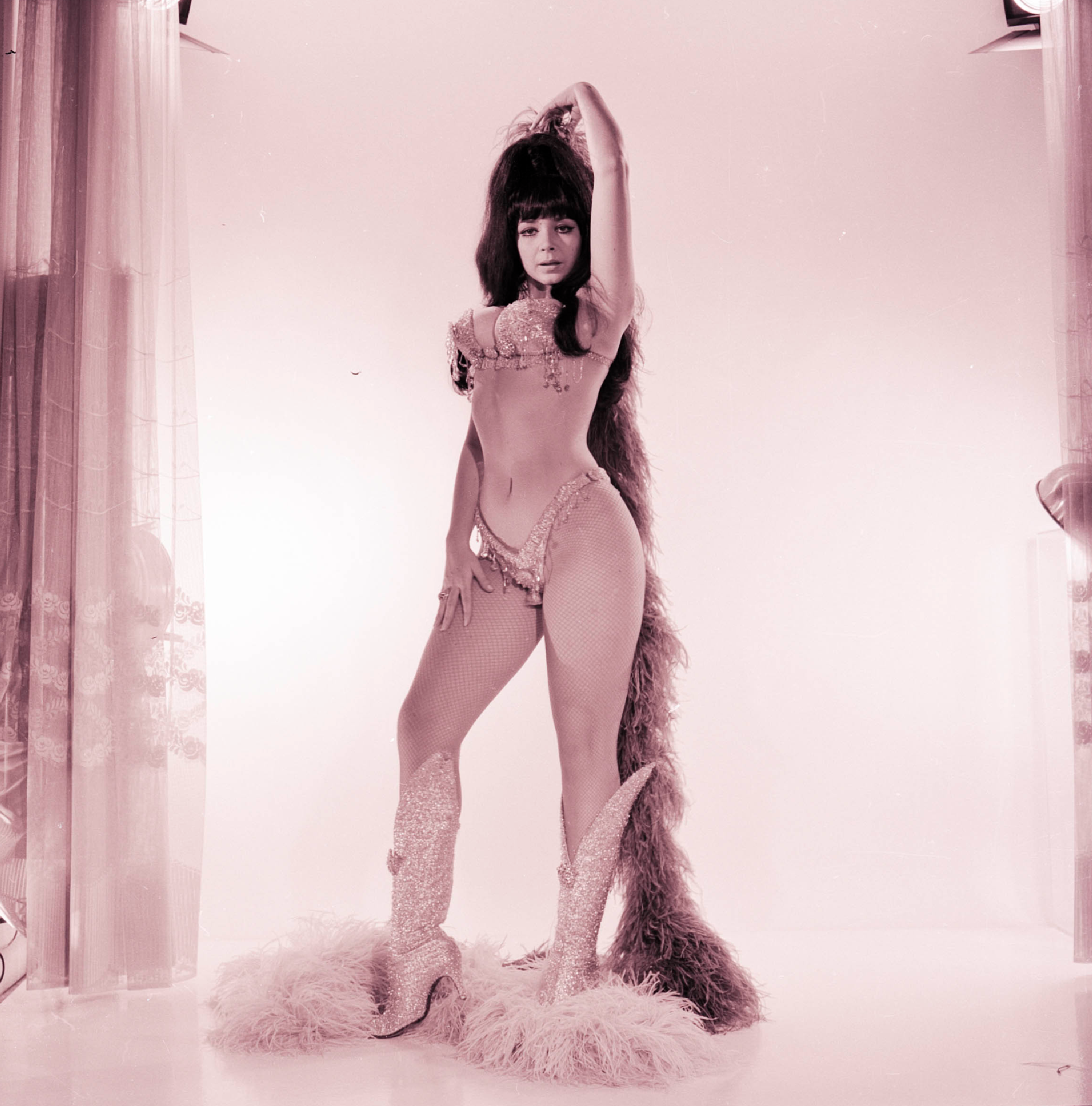

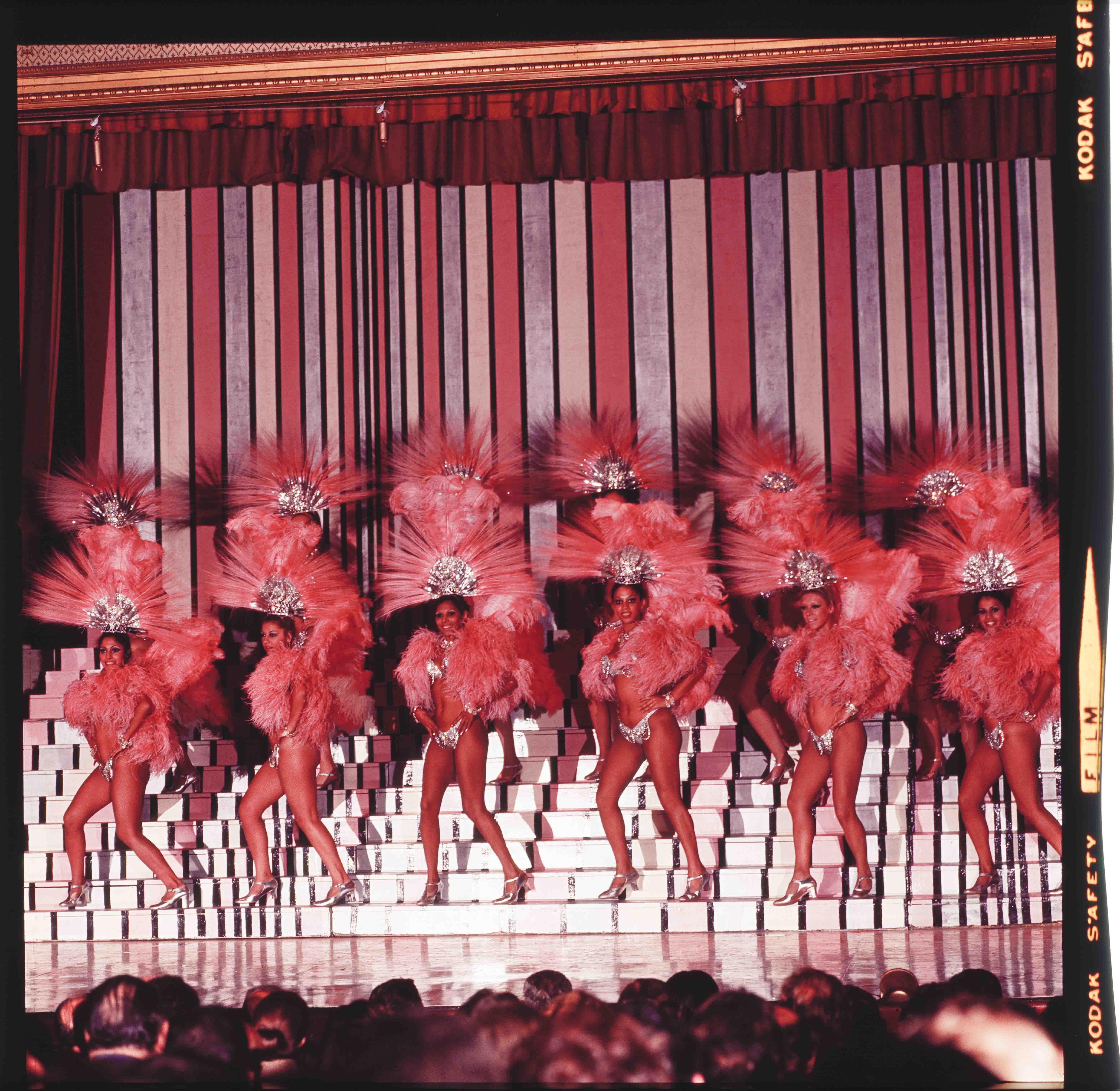

Their talent wooed audiences. Their sexual freedom gave women permission to break from their puritanical chains, and their glaring opulence enchanted the haves and the have nots. They sang, acted, joked and danced on stages donning luxe headdresses and stilettoed heels.

The Latin American showgirls of the mid-twentieth century were rockstars, but unlike their contemporaries in Old Hollywood, the careers of these bygone starlets haven’t been memorialized on terrazzo sidewalks. But, nearly a century later, Ficheraz, a Mexico City-based collective, has taken on the task of preserving their legacy with a digital, archival tribute to these beauties of the night.

Launched in 2018 by journalists who go by Rico and Daniela, Ficheraz is a multimedia project educating more than 100,000 fans around the world through Instagram posts that inform them of the past glories of vedettes while securing these women’s rightful place in Latin American entertainment history.

“This project is for people who want to learn about entertainment history,” Rico, Ficheraz’s primary researcher, tells Remezcla. “Yes, there’s some sex and nudity, but it’s about the history.”

The tale of how these once-desired showgirls were discarded by society is as gripping as watching them perform a violin number in a bedazzled bikini. In 1800s Parisian music halls and cabarets, showgirls were stage performers who played with themes of sensuality during their extravagant and skillful sets. The style then made its way from Europe to the United States to Mexico in the late 19th century and early 20th century, where fully-dressed performers used dialogue and body movements to allude to their sexuality.

Women admired them, not for their bodies, but for their talent.

The genre, widely relished, was considered acceptable for all ages at the time, and mothers often watched performances with their children. In the 1960s and ‘70s, the shows turned into exuberant productions and the women began unveiling more skin. Across theaters throughout Latin America, vedettes wrote, styled and performed sold-out shows. In the crowd, husbands spent entire paychecks on celebratory outings with their wives; both of them dressed in glamorous garbs. While the scantily-clad presentations of Olga Breeskin, Lyn May and Nelida Lobato, to name a few, might have tantalized some, most in the audience were enraptured by the natural aptitudes of the ritzy performers.

“It was never about how sexy they were. It was always about the show,” Rico says. “They were talented, and they were creatives. They came up with the dialogue and the choreography… Women admired them, not for their bodies, but for their talent.”

The favorable perception of showgirls began to wane in the late ‘70s. As the era of VHS movies commenced, new genres, including Mexico’s erotic comedies, known as cine de ficheras, were born. The low-budget films co-opted showgirl culture but elevated the vedettes’ salaciousness over their talent. The industry hired voluptuous models to play the roles of sexually explicit showgirls in their films.

On the one hand, men, who were the breadwinners of the family, opted for the inexpensive tapes to the high-priced theatrical productions. On the other, women, who began regarding showgirls as the one-dimensional sexpots they were characterized as in films rather than the talented creatives who performed on stages, started to condemn vedettes. Most of the real-life showgirls were of working-class backgrounds and lacked formal education. To survive in a rapidly changing industry, many felt forced into lascivious roles on film and stages. They started to perform sexual acts in front of cameras and audiences, roles many regret and refuse to discuss today.

“People got a different perception of the concept of showgirls, and women started having this idea that they were not going to see a class-act but rather a show that was too explicit,” Rico says.

For Ficheraz, part of preserving the legacy of Latin American showgirls is recounting and contextualizing this history. A few times a week, the group shares photos and videos of former vedettes from Latin America, the Caribbean and the diaspora with short biographies. Oftentimes, the bios are celebratory.

Recently, the team posted about Regina Dos Santos, an Afro-Brazilian showgirl who reached international fame when she pierced into Barcelona’s night scene with her captivating samba motions. Other times, they reveal the downturn of the industry and its devastating impact on vedettes. Among those stories is that of Argentine performer Princesa Yamal, who was wrongfully imprisoned for two years and eight months after audience members phoned the cops and accused her of stealing Aztec regalia, which was used during one of her performances.

They were freely expressing themselves at a time when women, in general, were supposed to be prude.

In sharing the performers’ complicated stories alongside images of them demanding stages with sparkling two-pieces and riveting belly sways, the showgirls have found fresh stardom among a new generation of women who are similarly captivated by their talent, sexual freedom, stunning garments and multidimensional lives.

“These women were freely expressing themselves at a time when women, in general, were supposed to be prude, so I feel like a lot of women [relate] to this topic and are surprised that a woman in the 1940s was making a career out of sexy dancing in conservative Latin America, that she was showing her body with no issues and being applauded for that,” Rico says.

While Ficheraz’s followers have a big appetite for content about vintage showgirls, research on the women is slight and difficult to come by. Ficheraz’s four-person team, composed of a researcher, a community manager and two modern-day showgirls, has devised their own library of films from the era and foreign texts about the art form. But most of their insight on the vedettes come from conversations with photographers who worked with the performers in their heyday and have given the team permission to republish their images.

Recently, Rico moved from Veracruz to Mexico City in hopes of meeting the aging starlets and documenting their stories, but the project has been halted by the COVID-19 pandemic. It’s his team’s hope to expand beyond Instagram and produce in-person and digital exhibitions about Latin American showgirls.

Currently, Ficheraz has been leading promotion for the documentary Foto Estudio Luisita, a film by Sol Miraglia that tells the story of the late female photographer Luisa Escarria who spent much of her life capturing the showgirls of the Argentine theatrical scene before falling into oblivion.

Stars like Beyoncé are inspired by showgirls.

While the extravagant careers of Latin American showgirls have similarly been forgotten, Rico says their influence, even if uncredited, remains visible, particularly among this generation’s biggest pop stars.

“Today, singers put on a show: they dance, they model and they wear flashy clothes,” Rico says. “Singers didn’t always do that. That’s what showgirls did. That was the job of a showgirl. Stars like Beyoncé are inspired by showgirls. Maybe they don’t know it, but it’s an extension of this art form.”