Chilean filmmaker Pablo Larraín (Jackie) had never really worked on a project that included many fantasy elements, so when he decided to undertake Lisey’s Story, a TV adaptation of Stephen King’s 2006 novel of the same name, he connected with the title character on a deeper level. In the series, Lisey Landon (Julianne Moore) isn’t sure how to handle the dreamlike scenarios emerging from her mind after the death of her husband.

“What was new to me were the elements of fantasy, which I had to embrace just like Lisey did,” Larraín tells Remezcla. “I had issues, at the beginning, connecting with that. Stephen was the one who told me that I had to believe in it first, so the audiences could, too.”

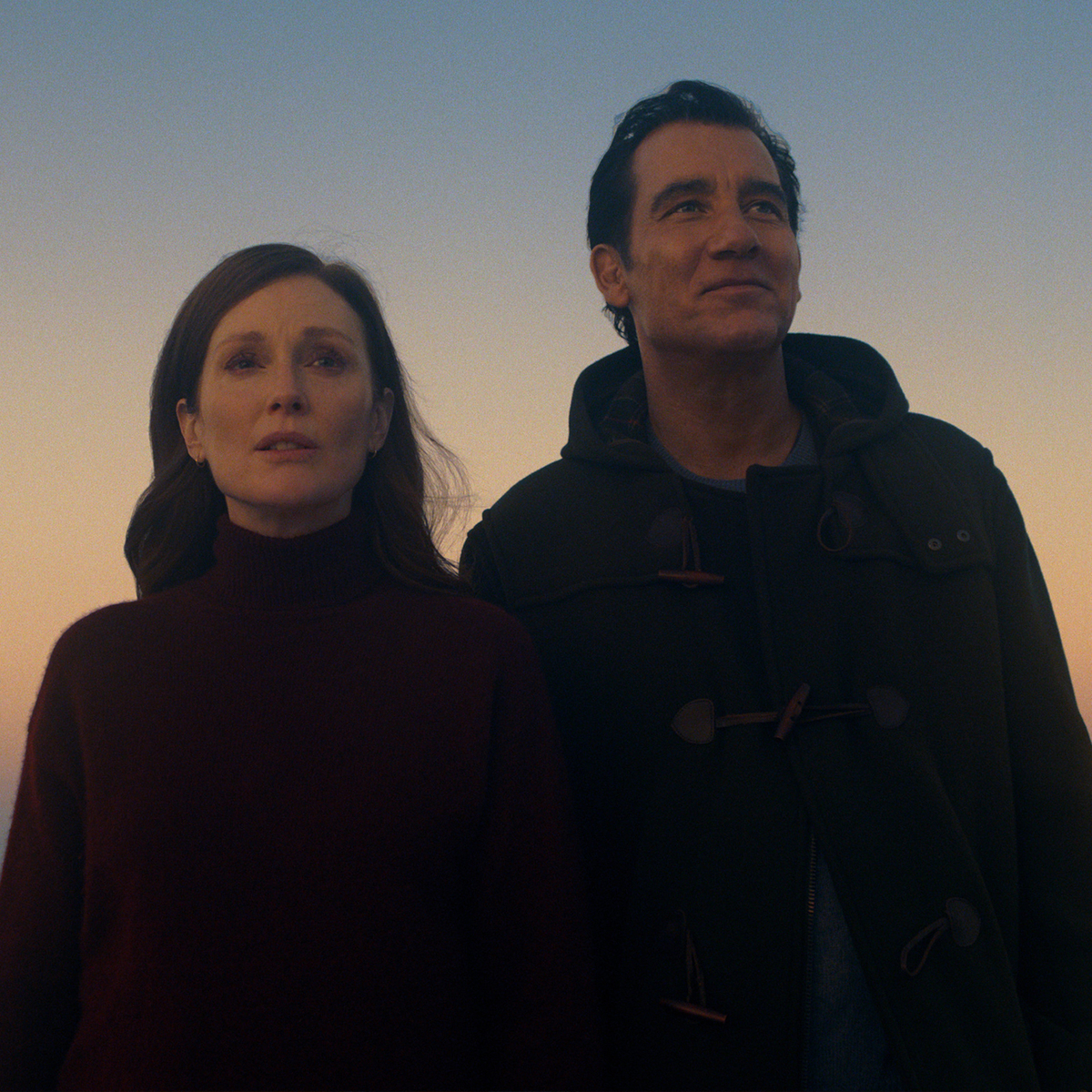

When Lisey’s novelist husband Scott (Clive Owen) dies, she must navigate her way through her memories of their lives together and her current life without him. King was inspired to write Lisey’s Story after his own near-death experience. In 2003, the best-selling author landed in the hospital with near-fatal double pneumonia. When his health began to improve, his wife decided to renovate his home office. Upon returning home with many of his possessions still in boxes, he thought that this must be what his office would look like after his death.

During our interview with Larraín, he talks about the universality of King’s novels, the humanity that comes from King himself and how he regards his own memories.

Lisey’s Story is currently streaming on Apple TV+. This interview has been lightly edited & condensed for clarity purposes.

What resonated with you about this specific Stephen King novel that made you want to take on this story?

I think it’s a wonderful story about memory and grief and how you put yourself together after the loss of someone. I think that’s something extremely universal and can be very beautiful depending on the process. It’s about the mystery of how Julianne’s [Moore] character can find herself again. Mostly, it was interesting for me to get to work with [Stephen] and Julianne and [executive producer] J.J. [Abrams] and everyone involved. Working with Stephen King material is usually very particular. For me, working with fantasy elements was a new experience. Fantasy is a poet level of a narrative… and Stephen is a contemporary poet.

So many of Stephen’s stories have been adapted in the past by different directors with different storytelling styles. Why do you think his work lends itself to so many perspectives?

I think there is something in Stephen’s work that is so universal and very broad. If you look at his body of work, you can find stories like Stand by Me and The Shining to something like Carrie and The Shawshank Redemption. It’s very wide in terms of the material he works with. I was very interested in getting to know him and to understand his process. I was very curious to know how his mind works. I understood that he cares about very simple, human things. The humanity that he can read and put on paper and that we can put on the screen, it’s something very deep and based in human emotions.

What did you learn about Stephen as a creative collaborator?

He is the first judge and censor of his own work. If he feels something is believable and possible about the humanity he’s expressing, then it would probably mean something for others. As an individual, he is fascinating. He’s funny and emotional and very connected with the people that he’s working with and talking to. There’s something in himself that I found very effective to work with. In this case, it’s a very personal story that’s related to his own biography. I felt like I had a big responsibility to put it on the screen in a way that he would feel comfortable. He’s very pleased with it, so that made me really happy.

Did you feel like you got an opportunity to see a side of Stephen other directors don’t get to see since he doesn’t always adapt his own work as a screenwriter?

He doesn’t usually do it because he doesn’t want to get involved in other people’s visions. I believe he likes the fact that people can go and take the material and turn it into something personal for the filmmakers. In this case, this was something very personal for him. So, he decided to write the script himself based on his own novel. For me, it was a big chance to get to work with him really close for a pretty long time. I went to the Stephen King School. I changed the way that I understand the narrative. It made me a different filmmaker. I’m incredibly grateful for that.

King is very pleased with it.

Is there something specific you learned as a filmmaker because you worked with him so closely?

There’s something in his personality that makes [the material] believable. He can make anything believable. He puts [an idea] in the ground with very simple tools that are based on human emotions. That might be easy to say, but it’s not easy to do it. That’s what my big lesson was after this process. There was something interesting in this process, which was the level of obstruction because it’s about fragments and pieces of memory. Sometimes it’s the memory of the memory of the memory. Those memories bring us back to the present and the emotions of that romantic relationship.

Your film Jackie, too, was about memory and grief. How do you think your work on your past films speaks to a series like this?

Yeah, I’ve made movies where there’s an individual who has a very specific state of mind that is in friction with the environment. That environment is also in a crisis, so the friction between the individual and the environment makes those movies work. In this case, the environment for Lisey is her memory. The environment that creates the crisis is the fantasy element that she doesn’t believe at the beginning. She begins to believe in it because that’s the way she can heal herself.

How far back do your own memories go?

I think it’s back to around four or five years old. My first memories are playing with my brothers and sisters when I was very little on the patio of the house where I grew up. What’s interesting is that memories are always related to an emotional moment. More than just the images you have, it’s the feeling those images have on you.

We’re all made of our memories, whether they’re good or bad.

Do you try to hold onto memories as you get older, or does it get more difficult?

Well, memory is a great tool to work with. I come from a country that has issues with memory. Some people don’t want to remember what has happened in [Chile] and some people do. I think our country right now is changing because we are now facing our own memories. We are using those memories to reorganize our system to look towards the future. When you do that, I think you can really heal and move on.

If you could erase bad memories like in Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind, would you do that?

I wouldn’t. I think we’re all made of our memories, whether they’re good or bad. That would create a different version of myself. I don’t think that’s a good idea. I think if you accept your own past, the better you are prepared to deal with the present and the future.