Though anti-Blackness is a global disease, the Dominican Republic has become a case study of how internalized racism can quickly turn to cruelty. In 1937, the regime of Dominican dictator Rafael Leonidas Trujillo executed thousands of Haitians living along the Massacre River to redraw the border between the Caribbean sister nations. Just this month, the same narrow river regained its battleground status as Dominican President Luis Abinader shuttered all trade and transit with Haiti in an escalating dispute over a new canal planned to quench regional drought. While the development is a matter of water access, the president’s growing rhetoric of a “Haitian Invasion” coupled with the humanitarian crisis triggered a decade ago by the elimination of birthright citizenship paint a damning, recurring precedent.

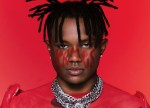

Then come those who wield generational memory as an antidote for hate and prejudice. 23-year-old Dominican rapper Inka has long understood that responsibility, empowering fellow young people as a history and geography teacher throughout the pandemic and unpacking mental health and racist microaggressions on early singles “El Pozo” and “Jarabe.” But on his impressionistic debut album Villa Mella, his focus shifts to heritage and diasporic legacy, examining his role and surroundings as a son of one of Santo Domingo’s bastions of Black resistance.

“This isn’t just art to me,” Inka tells Remezcla, speaking from Santo Domingo over Zoom. “This whole project is about connecting with my community and my Afro-descendance. It’s about connecting with my abuela’s practice of santería, which my family has always treated as a ‘we don’t talk about Bruno.’ She could channel spirits, but my family never allowed me to connect with that, and this album started becoming an excuse to go there and dig deeper.”

The district of Villa Mella starts where the Santo Domingo metro ends: at a station poignantly named after murdered land rights activist Florinda Soriano, aka Mamá Tingó. It’s also where the urban sprawl of the Dominican capital turns to smaller rural communities such as Los Moreno and Mata Los Indios, all of which are living, breathing characters and set pieces across Inka’s opera prima. Lead single “Party de Palo” unfolds like a checklist of Villa Mella’s historical significance — a community built by cimarrones (escaped slaves), later a refuge for independence suffragist Ramón Matías Mella, and a unique ecosystem where the Dominican Republic’s African ancestry still lives and breathes.

Villa Mella‘s sonic omnivorousness is dazzling, blending handcrafted drums and tambourines (called palos and panderos) with synthesizers and digital drum pads. On “Vámono Pa La Ocurida,” performed alongside Yorniell, a chant to the Orisha Elegua gives way to raunchy perreo, palo drumming, and a synthpop nightclub. Meanwhile, the song finds duality in our instinctual fear of darkness and how, once upon a time, the night cloaked cimarrones to safety. On “Palo,” Inka invites rappers Bigoblin, Dinamita, and Leamback for an effusive dembow celebration of Enerolisa, the legendary cantadora and queen of música de salve. Both songs nod to the electronic sequencing of dembow and reggaeton, as well as their roots in Afro-diasporic rhythms pri-prí and congo de Villa Mella. But to achieve this hybrid of tradition and contemporary production, Inka needed to tap a legend.

“Working with Evaristo Moreno is an honor and a pleasure,” he says of the revered multi-instrumentalist and producer who helmed the album’s textured sound. “I remember finding a record called Villa Mella Querida [from 1993] by the son ensemble Bartolito y Los Bravos del Son. I showed it to Evaristo, and it turns out he used to play with them. He also played with [jazz fusion luminaries] Toné Vicioso, Jabid & Ararey, and Los Hermanos Moreno. This last one was with his brother Mauricio Mercedes, who was a pillar of pri-prí, a rhythm from Villa Mella that’s slowly becoming extinct. Evaristo is keeping this music alive, teaching it to younger people in the community, but he’s also super creative and can innovate and perform outside tradition.”

Even though guardians of these rhythms, such as Enerolisa, Evaristo Moreno, and La Cofradía del Espíritu Santo, seldom get their flowers, Villa Mella’s influence on Dominican music is undeniable. From academic masterpieces like Xiomara Fortuna’s Kumbajei (1999) to Kinito Mendez’s Latin Grammy-nominated merengue blockbuster A Palo Limpio (2001) and recent jazz and indie favorites by Vicente García, Yasser Tejeda, and Pororó, música de palo is Black and deeply syncretic. These are themes that also shine through Inka’s vivid storytelling.

“As I started working on these songs, I wasn’t sure how deep I’d go… The album examines my own Afro-descendance through genealogy, spirituality, economics, and even institutional injustice.”

“As I started working on these songs, I wasn’t sure how deep I’d go,” he says. “’Party de Palo’ became a philosophical dismantling of anti-Blackness. ‘Limones’ looks at the stories of my mother and father and how their impoverished experience shaped their lives and later mine. In ‘Ay Mami,’ the line ‘Los misterios de mi abuela persiguieron a mi mai’ refers to my grandmother’s passing and how rumors and fear of santería haunted my mother. So the album examines my own Afro-descendance through genealogy, spirituality, economics, and even institutional injustice in ‘Guaricano.’”

In a way, “Guaricano” is a perfect summation of Villa Mella’s kaleidoscopic arsenal of references and messages. First, Inka anchors his theatrical bars in the influential style of OG Dominican MCs such as Lapiz Conciente and Monkey Black while slashing through government corruption and police brutality. The melodic backbone of Cuban son is brought back to Villa Mella with Evaristo Moreno plucking at his cuatro. An evocative flute melody composed by indie pop producer Shy Melomano and performed by flutist Ezetumbao also flutters about, harkening to Dominican Fania architect Johnny Pacheco.

The song, and ultimately the album as a whole, weaves trans-continental, cross-generational stories into a single rich sonic tapestry. Always narrated in community and super-charged with soul.

Listen to Villa Mella below.