In 1993, when Aterciopelados hit No. 1 on Colombian radio with their demo recording of “Mujer Gala,” it was a punk scream that ushered in a new age of homegrown popular music. Three decades later, the irreverent duo of Andrea Echeverri and Hector Buitrago would reimagine the classic during a sold-out anniversary concert at Bogota’s famed Palacio de los Deportes. Only this time, they weren’t just scraggly rolos (i.e., Bogota natives), but canonized rock en español legends joined by fellow alter-latino trailblazer Rubén Albarrán of Café Tacvba.

The “Mujer Gala” revamp was released as a single this past August, ahead of a forthcoming live album and tour kicking off in Canada this fall, stretching through the U.S. and wrapping in Australia early next year. It’s the cherry on top of a grueling anniversary cycle celebrating Aterciopelados’ quirky tropical rock legacy and, more specifically, 28 years of their landmark sophomore LP, El Dorado. “The plan was actually to celebrate 25 years of El Dorado, but then the pandemic happened. It’s not that we’re weirdly obsessed with the number 28,” Echeverri tells Remezcla.

Before hits like “Baracunatana” and “Bolero Falaz” became Saturday night karaoke staples, Echeverri and Buitrago were artsy kids toiling in Bogota’s bare-knuckle underground. In the mid-1980s, Buitrago found success with seminal hardcore band La Pestilencia but had grown tired of the punk scene’s infrastructure-less precarity. In 1988, a friend introduced him to Echeverri, and they soon began dating and rehearsing under the name Delia y Los Aminoácidos. They opened a bar called Barbarie in the Bogota neighborhood of La Candelaria, which became a scene hot spot where Buitrago programmed fresh rock en español releases while Echeverri designed flyers and the space’s chameleonic aesthetic. Both the bar and their relationship folded in 1990, but they’d regroup three years later as Aterciopelados, spearheading a homegrown alt-rock revolution.

“When I started setting up the bar and working on other projects, the intention was to define our identity,” remembers Echeverri. “Lots of bands sang in English and looked outside for inspiration. But this was the ‘90s, so we bet on música Bogotana. We wanted the lyrics to sound how we talked and to dress how we dressed. There was also a big influence from popular culture and kitsch. San Victorino was this really esoteric neighborhood where religious and folk imagery intersected; El Indio Amazónico, El Negro Felipe, María Lionza. We were living our city.”

“Mujer Gala” and the rest of their 1993 debut Con El Corazón En La Mano was anchored in the buzzsaw riffs Buitrago honed in La Pestilencia. However, those same noisy riffs found new dance partners on their 1995 follow-up El Dorado, where Colombian identity took center stage in all its sonorous, chaotic, multi-cultural splendor.

“Lots of bands sang in English and looked outside for inspiration. But this was the ‘90s, so we bet on música Bogotana. We wanted the lyrics to sound how we talked and to dress how we dressed.”

On “Florecita Rockera,” grunge and reggae are gleefully woven into tie-dyed hippie joy, while “Candela” unfolds like a thunderous explosion of Afro-diasporic drums. “La Estaca” ping-pongs maniacally between hardcore and música ranchera, while the kooky salsa-punk of “Colombia Conexión” maps out a country of contrasts — prideful of their music, natural resources, and sporting prowess, and weary of cartel violence and U.S. intervention. Aterciopelados were fusing imported sounds and homegrown traditions, becoming outliers of the increasingly homogenous rock en español space. El Dorado made them a counterculture within a counterculture.

“On the first album, we had some fusions, but after the success of ‘Mujer Gala’ and with the support of [major label] BMG, we got really ambitious on El Dorado,” remembers Buitrago, who helmed the record’s hybrid sound alongside producer Federico López. “There’s rancheras, Andean melodies, these huge Caribbean drums. The album captured the eclecticism and experimental freedom that has come to define our band since. We had the audacity to explore different genres without being experts, and were criticized for it by our more purist rock peers.”

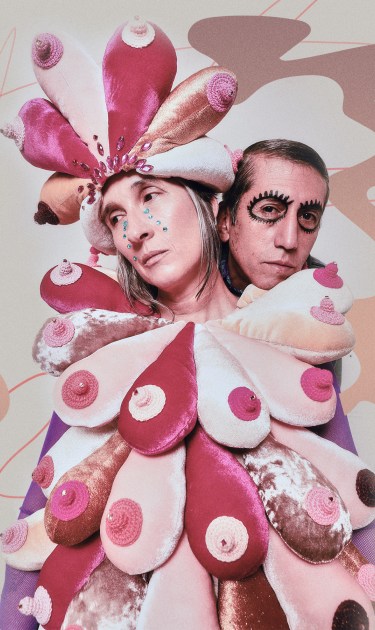

Aterciopelados’ visual storytelling also became a career hallmark, shapeshifting from dreadlocks to shaved heads to intricate hand-crafted installations perched atop their heads during live shows. Even in 1995, in the technicolor video for “Bolero Falaz,” Echeverri’s neon bohemian ensemble contrasted sharply against the rolo uniform of all-black attire–a perfect balance of jarring rebelliousness that made them early MTV favorites. Subsequent albums, including Pipa de la Paz (1997) and Caribe Atómico (1998), also achieved blockbuster success by savvily tapping into the zeitgeist of electronic music and hip-hop.

The band’s fearless fusions have always been accompanied by cutting satire, leveling risky social critiques at a time when government corruption, guerrilla violence, and a withering war on drugs ravaged Colombia. That insurrectionist flame still burns brightly, and back in 2021, the duo released a string of poignant feminist anthems recorded in collaboration with artists such as Vivir Quintana, La Muchacha, and Las Añez. And yet, despite the groundbreaking art and undeniable pop success, Aterciopelados continue fighting for their seat at the table.

In October 2022, the band was tapped to open two shows for Guns N’ Roses’ highly anticipated return to Colombia but were denied a sound check. This led Echeverri to rail against the California rock legends, later apologizing for the incident. While she wisely boasted about how excellent they sounded, barring the unfavorable working conditions, the incident still begged a larger question of how the region prioritizes foreign, white, English-language music over ours. If Aterciopelados can’t get a soundcheck, who can?

“We perform abroad more often than in Colombia,” says Echeverri. “But we are loved by the people. We symbolize freedom and joy. Old ladies on the street greet me and kiss me, but it’s also been challenging for us at this time when other musical genres reign supreme. In some way, we represent criticism. But we’re also pros and have been doing this for 30 years, so even if we don’t get a soundcheck, we can still go up there and kill it.”

“We perform abroad more often than in Colombia. But we are loved by the people. We symbolize freedom and joy.”

Aterciopelados are the patron saints of Colombian alt-rock, but time has also taken its toll. Tensions between Echeverri and Buitrago came to a head in 2011, and they officially disbanded for three years, reuniting in 2014 for the 20th anniversary of Rock al Parque, an annual free rock festival in Bogota. They used the time apart to immerse themselves in solo careers — Echeverri on her LP Ruiseñora and Buitrago with electronic project Conector — which ultimately rejuvenated their creative relationship. Echeverri would later unpack the nature of their serendipitous partnership on the song “Dúo” from 2018’s Claroscura.

“It was really important when we fought and broke up,” says Echeverri. “I had to produce my own solo material and Hector had to stand in front of a microphone for us to realize that those are not our specialties. He’s not a singer, and I’m not a producer. So when we get together, it’s wonderful because we both excel. It’s so hard to find someone who, after 30 years, is still there, willing and able. Finding each other was divine luck.”