When thousands of Haitians began to arrive at the US-Mexico border in early spring 2016, local and international journalists jumped on the story and captured Haitians at their most desperate moment – as they looked for refuge wherever they could find it in Tijuana. Headlines often focused on Black suffering but often didn’t give space for Haitians to tell their own tales. Today, Tijuana is booming with Haitian artists, musicians, and writers. And some, like Pascal Ustin Dubuisson, are determined to take ownership of their stories and present new narratives in his new home, Mexico.

Emerging writer Pascal Ustin Dubuisson was born in Port-Au-Prince, Haiti and like thousands in his homeland, the political and economic crisis forced him to flee in search of opportunity at the age of 21. Given an established stream of migration from Haiti to Brazil, he made his way to Rio de Janeiro. After Brazil hosted the 2016 Olympics, the country hit an economic recession and Dubuisson decided to leave Rio de Janeiro after two years of inconsistent work. He then headed for the United States in hopes of reuniting with his Mother and sister in Miami, Florida.

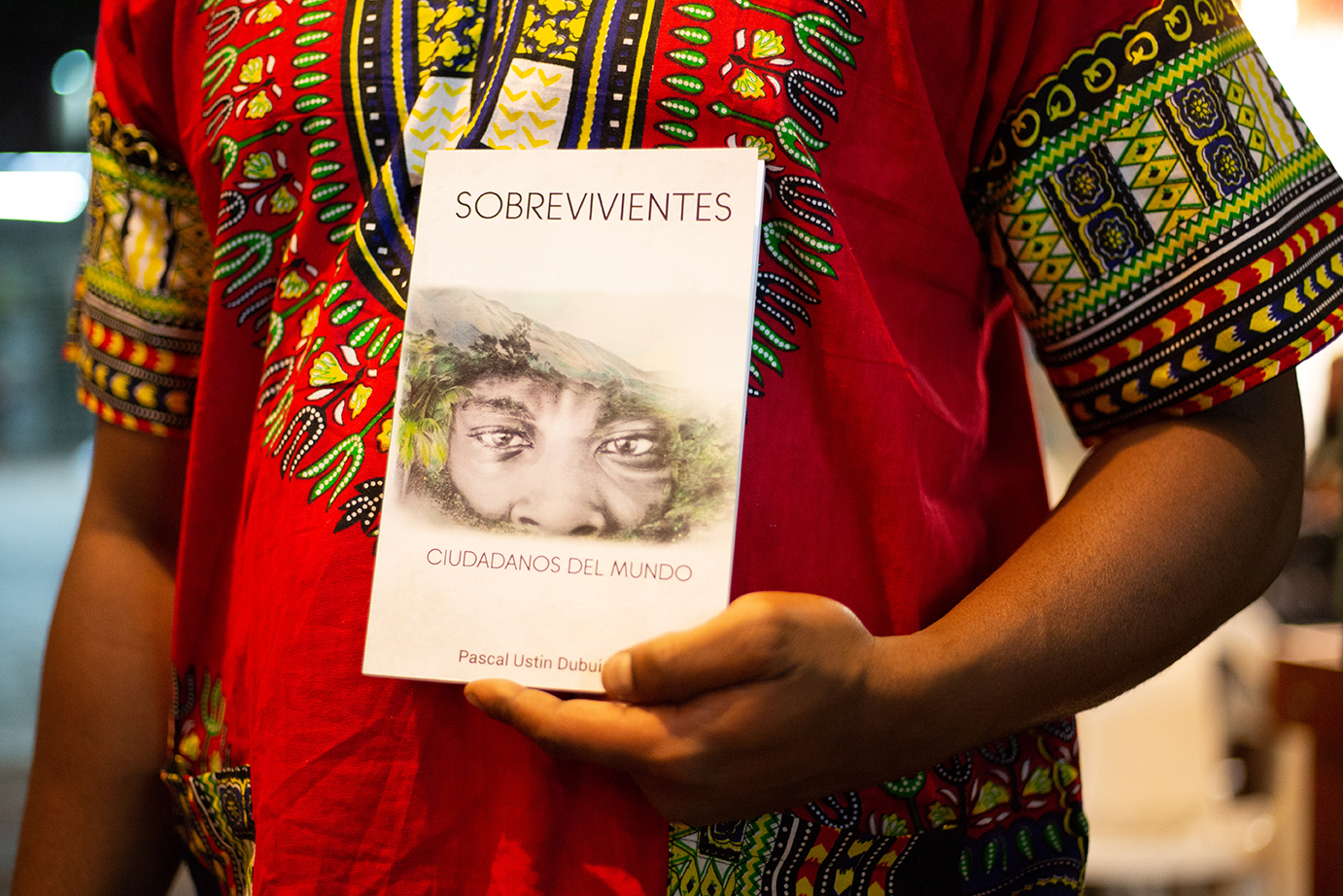

The journey would lead to Sobrevivientes. Ciudadanos del mundo, the first book published in Mexico about the Haitian immigration experience. Authored by Dubuisson, the book is a personal account of what he witnessed and lived through for four months as he migrated north, crossing through 10 countries, including Peru, Colombia, Panama, and Costa Rica.

“I started to work on the book when I was on my journey from Brazil.” he tells me. “I would document things with my cell phone and write about what was happening for my family back home. When I arrived to Nicaragua, all of my belongings were stolen including my phone.”

After losing everything Dubuisson felt discouragement but the author had a change of heart when he reached Tijuana, Mexico: “When I saw that many reporters were interested in the story of Haitians, I felt motivated to continue writing to share what the journey was really like.”

Originally written in French, Sobrevivientes is now available in Spanish. It’s also receiving attention at universities, such as Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México (UNAM), and in community forums throughout Mexico.

“I would document things with my cell phone and write about what was happening for my family back home.”

Through 154 pages, the Haitian writer recounts his four-month quest through dangerous terrain, including the dense jungle of the Darién Gap between Colombia and Panama. “The crossing of the Darien Gap was the worst because that’s where I saw people die. I almost died there,” he says. “Also, at the border with Costa Rica and Nicaragua I saw how much human life was dependent on others in order to survive. Sometimes we were left starving with no food. I went nine days hardly eating anything at all and witnessed people die of weakness.”

Throughout Sobrevivientes, Dubuisson describes a journey of disparity, death, and extreme uncertainty. One excerpt reads: “Fortunately my friend had some crackers, salt and sugar. We mixed water from a nearby creek with the salt and sugar to make a hydrating serum. We drank the serum and ate the the crackers then made a fire to keep wild animals away.”

In 2016 alone, a recorded 17,078 Haitians crossed into Mexico, and Dubuisson said that at the time, it felt like a race to reach the United States before the presidential elections took place. As anti-immigrant rhetoric became the focal point of the elections and asylum flexibility was on the verge of stiffening, it’s no wonder that many attempted to cross the border then. In total, a mass migration of about 20,000 Haitians moved over two years from Brazil to the US-Mexico border to seek asylum. Today, Haitians are the second group to most likely be denied asylum into the U.S. only superseded by Mexican asylum seekers.

As the largest border city, Tijuana is compared to New York City for its attraction of diverse migration and cultures often merging together. Tijuana becomes home to many that originally intended to cross into the US and Dubuisson relates to this trend as a Haitijuanense. “Like many, I decided to stay in Tijuana to work,” he says. “Yes there is an ‘American Dream’ and here, there is a ‘Mexican Dream.’”

It’s estimated there are more than 3,000 Haitians currently living in the border city. Dubuisson has started a family with a Mexican partner and has a 9-month-old son named Andre, who he plans to raise in Tijuana.

Dubuisson, now 25 years old, believes Sobrevivientes is helping to carve a place for the Black diaspora in Mexico. So far, an author tour has taken him to Mexico City, Queretaro, Mexicali, Ensenada, and Guadalajara, where he’s connected with fellow Black artists and activists.

“The Afro-Latinx community in Mexico City is very interesting. I think my book sheds light on Black culture. My book is not only a marker for the Haitian experience, but it also builds on the stories of Black Mexicans and migrants in this country. I think this is an important moment for people to raise their voices. I do this work so that our rights are respected and to build support. I think we deserve it,” Dubuisson says. “My son Andre is Haitijuanense. I think the work I am doing with my book right now will eventually open paths for him as a Black boy in Mexico. I want him to have opportunities and I want him to know his Haitian heritage. Hopefully he will learn to speak five languages.”