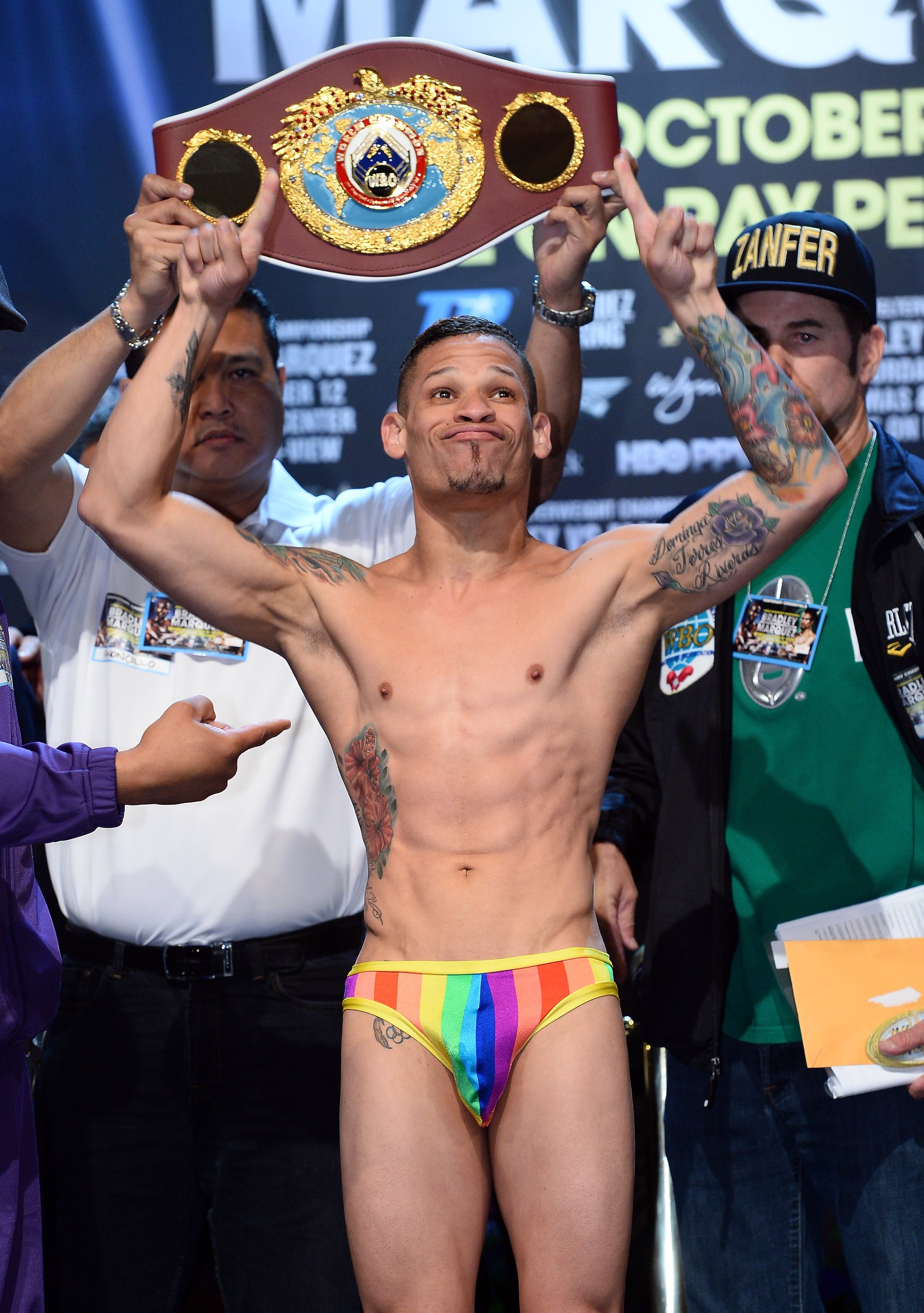

On Saturday, while most of boxing’s audience focused on Andre Ward controversially defeating Sergey Kovalev in their rematch, Orlando Cruz lost to Jose Lopez with little fanfare. There were no HBO, Sports Illustrated, or even Univision camera crews. There were likely no writers from The New Yorker, The Guardian, or ESPN—all of whom once flocked to cover Cruz who, since coming out publicly five years ago, has attempted to become the first openly gay boxing world champion.

On Saturday, the lights of Vegas evaded him, Cruz fought Lopez in Caguas, Puerto Rico, inside the Coliseo Roger L. Mendoza. The Coliseo is a small venue that is, literally and figuratively, thousands of miles away from The Strip, where Cruz had his first world title shot in 2013, losing to his tocayo, Orlando Salido.

Cruz’s loss does not signal his career’s end but, with the WBO International 130-pound title at stake, the loss means any realistic title-shot is likely over. Cruz turns 36 next month, an advanced age for a professional boxer, an age when reflexes and quickness slow, and the already dangerous sport can become deadly.

There was evidence of this decay on Saturday, but this is how it ends for boxers. There are no final seasons acting as farewell tours in boxing. Only dwindling crowds, the odd type to watch a once-beautiful athlete punished by opponents who, in another life, were hardly good enough to offer competitive sparring sessions.

Orlando Cruz lost on Saturday but it does not take away from his importance. To appreciate Cruz, we must first understand the history of homophobia in boxing—told through two fights. The most famous, occurring 55 years ago, was also the most tragic. While the second, and most recent, highlights the Latino culture’s machismo that is an inherent part of boxing.

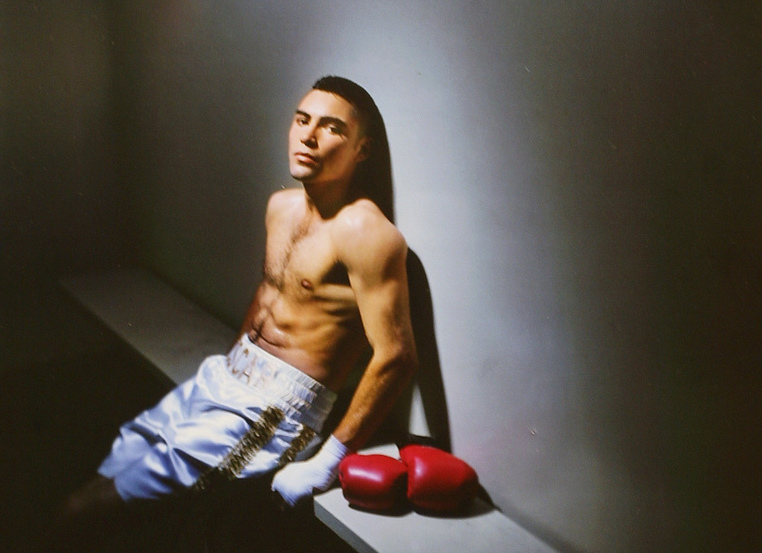

Emile Griffith never meant to kill Benny Paret. During the 12th round of their 1962 fight, Griffith pounced on Paret, who had stumbled into the corner, unable to protect himself. Griffith landed 27 uncontested punches before the slow-acting referee stopped the fight. “When I saw Paret hurt,” Griffith said afterwards, “I want[ed] him…on the ground before the fight was stopped.”

With the fight over, Paret’s body slid down the ropes into a seated position; legs crumbled beneath his body while leaving his right arm hanging from the ropes. His cornermen jumped into the ring but all they could do was unfold his legs and lay him on his back—a more dignified position for a former world champion—before carrying him out on a stretcher and taking him to the hospital. Doctors drilled holes into Paret’s skull to relieve pressure from the swelling caused by cerebral lacerations. When Griffith learned of Paret’s grave condition, he cried inconsolably. Ten days later, Paret passed away, changing Griffith irreparably.

The death haunted Griffith, who’d wake up to Paret standing at the foot of his bed. Hard to tell if the apparitions were any better than nightmares of greeting Paret on the street, going to shake his hand only to find it lifeless and cold. Or the other nightmare, that of attending a boxing event and realizing he was sitting next to Paret as they both watched boxers trying to kill one another.

“I kill a man and most people forgive me. However, I love a man and many say this makes me an evil person.”

Griffith never meant to kill him but also admitted “what [Paret] said touched something inside.” Leading up to their fight, Paret—from Cuba—had called Griffith a “maricón.” For the unaware, Griffith offered a translation: “Maricón in English means faggot.” But more than that, Paret publicly taunted him. During their pre-fight weigh-in, coming off the scales, Paret moved behind Griffith, grabbed his ass and, making a thrusting motion, said, “Hey maricón, I’m going to get you and your husband.” It is unclear how much the slur played in the tragic result but Paret used it, knowing it would cut at Griffith, whom rumors pegged as gay.

During his career, Griffith never substantiated the rumors—likely impossible, in the 1960s, for him to continue his career had he done so. This was boxing, the same sport that a generation earlier shunned then-flyweight boxing champion Panama Joe Brown because he “loved other men.”

Instead, Griffith remained quiet, only admitting to struggling with his sexuality decades after he retired. “I will dance with anybody,” Griffith offered as a metaphor in explaining his sexual preference. “I’ve chased men and women. I like men and women both. But I don’t like that word: homosexual, gay, or faggot. I don’t know what I am. I love men and women the same, but if you ask me which one is better…I like women.”

This admission came after Griffith almost died in 1992, thirteen years earlier, a victim of a hate crime. Griffith, who suffered brain damage from the beating, remained lucid enough to understand the great dichotomy of his situation: “I kill a man and most people forgive me. However, I love a man and many say this makes me an evil person.”

It wasn’t as if Paret calling Griffith a “maricón” was the last episode of homophobia in boxing; it was merely the most tragic. Its most manic came with Mike Tyson’s hate-filled rant in 2002. A more recent and–because of those involved–better known example came in 2006. Leading up to their fight, Ricardo Mayorga repeatedly questioned Oscar De La Hoya’s sexuality and manhood.

Mayorga was not the first to do it, just the most overt in doing so. When he questioned De La Hoya’s sexuality, it was closely tied into manhood and ethnic authenticity—an issue that presented itself throughout De La Hoya’s career. Whether fighting Latinos like Félix Trinidad, Mexican nationals like Julio César Chávez, or Mexican-Americans like Fernando Vargas, part of the debate revolved around De La Hoya’s manhood and authenticity.

During a press conference, the ever-volatile Mayorga screamed at De La Hoya. “I am the champion, you are no one…you’re nobody, maricón…Give me my respect, maricón.” Mayorga also talked about De La Hoya’s wife and questioned his Mexican authenticity. “I am the champion, you clown,” Mayorga yelled, “You don’t even know how to represent your race, maricón. That’s why all the Latinos are with me…even Mexicans…Not even your race likes you because you don’t know how to represent.” Mayorga claimed his dislike of De La Hoya stemmed from the latter’s defeat of Julio César Chávez—the symbol of Mexican boxing machismo.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hFSWwK5KhJU

Despite the vitriol, De La Hoya’s supreme skill overpowered Mayorga, dropping him with a right hook, just a minute into their fight. Mayorga lasted until the 6th round before the referee stopped the bout. The fight ended with Mayorga on his knees, trying to regain enough equilibrium to struggle onto his feet, while De La Hoya—carried atop his trainer’s shoulders—celebrated with an uncontrollable smile.

After the fight, reporters asked De La Hoya what he thought of Mayorga. He responded, “Well it’s not that I don’t like him, or I hate him. I don’t even know the guy. It’s just ever since he started disrespecting me, disrespecting my wife, disrespecting my family, he insulted my heritage—when opponents talk like that, you have to defend yourself.”

De La Hoya never brought up, Mayorga’s attacks on his sexuality.

Cruz was boxing’s great anomaly; openly gay in a sport that exudes masculinity.

These fights are a sliver of the history of homophobia within boxing that Cruz came out to. On Saturday, that was likely the furthest thing from his mind as, frequently, he appeared on the verge of being knocked down, even out. His experience allowed him to endure the beating, holding on to his younger and taller opponent, hoping to survive long enough to hear the score cards read. He did, and the most sympathetic of them had him winning only 3 of the 10 rounds.

Maybe this was Cruz’s last fight and he will walk away. But Cruz is a boxer, above all else, and even if he “retires,” the pull of the ring may tempt him into continuing, convincing himself that a world title is within reach.

Cruz was not a transcendental boxing talent—few are—but he was an important one. He was boxing’s great anomaly; openly gay in a sport that exudes masculinity and dominated by a Latino culture inseparable from its machismo. In a sport synonymous with bravery, Cruz fought for and against a variety of things, making him among the bravest of them all.