Last night, the Toronto International Film Festival hosted “In Conversation With… Gael García Bernal,” an hour-and-a-half talk between the Mexican actor and film journalist Juan Carlos Arciniegas. Bernal was present at the festival to premiere his latest film, the French project If You Saw His Heart, and over the course of the evening, he shared lots of insights about his career as well as his philanthropic and politically-motivated work.

We learned Bernal has thought about running for office (he already has our vote), that he owns a rebozo (and sees it as a small victory in the long fight for women’s rights), that his characters stay with him for years (“they become like cousins of mine,” he said), and that yes, he’s headed to the stage soon, in a play that might take him to Argentina and Spain.

Take a look at some other highlights from the chat below.

On Why He Never Wanted to Become an Actor

“I decided to travel, to Europe… I was working at a bar, undocumented, serving beers and I said, “What am I gonna do? I’m a little bit bored.” I auditioned for Central School of Speech and Drama and I got in.

There are many things I wanted to be. If I wasn’t here I’d have been a rural pediatrician. It’s true! I wanted to be a doctor. Journalism was [also] something that interested me. Philosophy, anthropology, sociology. I entered Philosophy in the UNAM in Mexico. Not to be a philosopher as such but the openness that philosophy can give you. I didn’t know if I wanted to go into Literature or Academia. But I always enjoyed acting […] and that’s because my parents are actors. I wanted to do everything I could to not be an actor! But there was a student strike at UNAM in 1997. For one year there was a student strike and I decided to travel, to Europe because I’d never been. Bought a ticket to London. The money ran out in three days. […] So I was working at a bar, undocumented, of course, serving beers and I said, “What am I gonna do? I’m a little bit bored.” So I went to see the drama schools — because, you know, the London stage has such a reputation! I was like, let’s see the schools of theater how they are. I auditioned for Central School of Speech and Drama and I got in. Then I had to get my act together and see how I would stay there studying theater for three years.

On Coming to Terms With Fame

At the beginning it was very complicated for me. When I did Amores Perros I never expected these films to have any absolutely any transcendence. I actually asked the producers for a VHS copy of the film; and I thought “this is so wise of me!” To say “give me a VHS” because I want to show it to my family. I never got the VHS copy! It wasn’t necessary. It was a film that was seen all over the world. And then there was a lot of attention that was put on all of us who participated in that film. You know, it’s an etymological mistake we make when we say someone is famous (“alguien es famoso”). It’s not them who are famous. It’s the outside people who perceive you as famous. You don’t wake up one day being famous. Like, looking at yourself in the mirror and going “I’m famous!” It’s really different from waking up and getting a pimple. That’s something that happens to you. It’s not perception. Fame is an outsider’s thing. It’s not yours. And you have to fight it. I mean fight it in terms of coming to terms with it. Because I didn’t want it. I didn’t look for it. And then all of a sudden you get recognized on the street for doing work you really like—that’s very nice! But at the same time, it’s something that’s happening on the outside.

On Learning From Alfonso Cuarón On Set

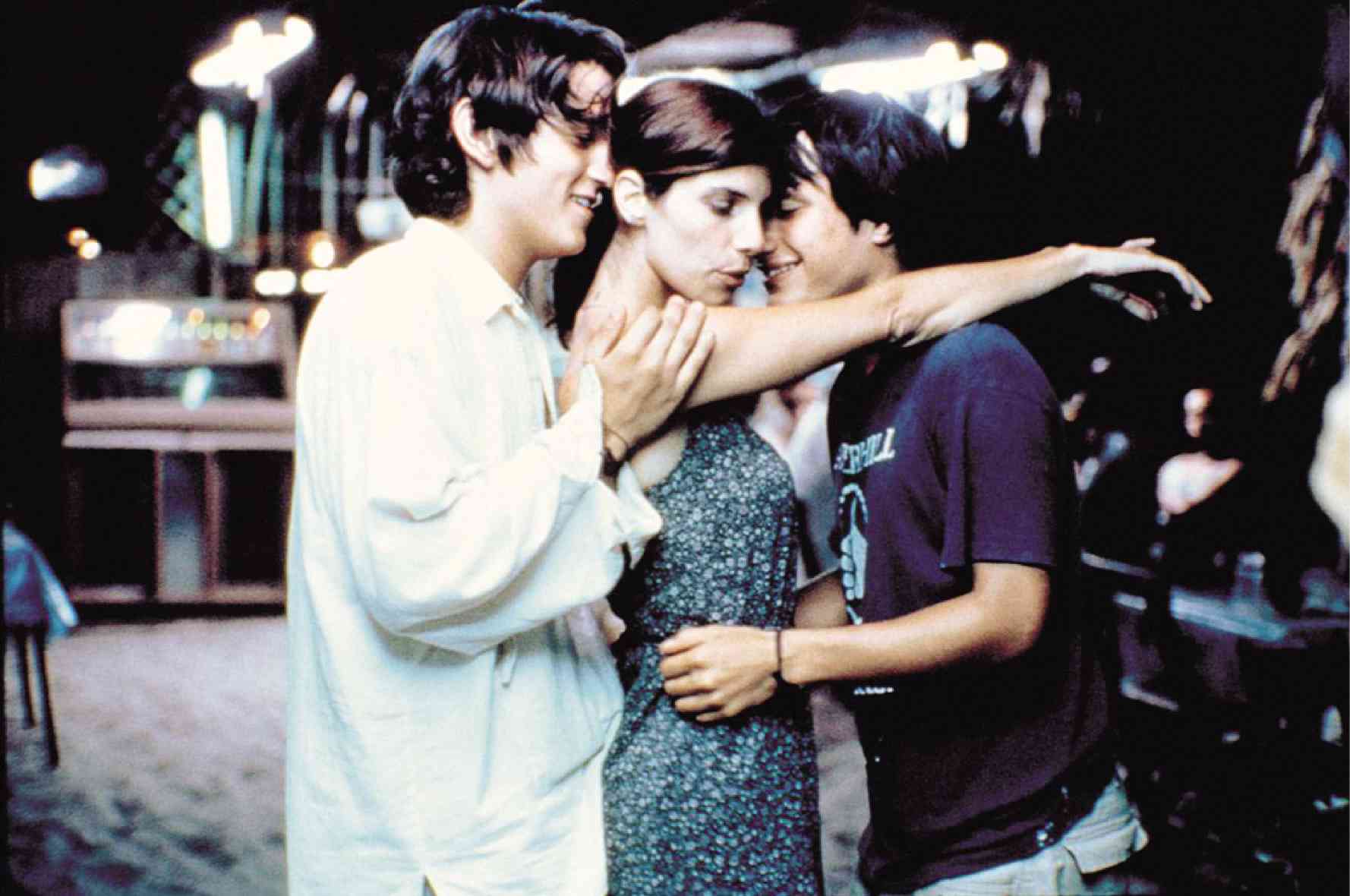

I had no idea what I was doing in Amores Perros. Making films was so far away for me. There were only 6 films made in Mexico that year. And Mexico had a huge industry in the 30s and 40s. We have a huge pantheon of stars and directors. Amazing people who made amazing movies. But in the late 90s the film world completely collapsed. Only 6 films! And one of them was Amores Perros — see why I asked for that VHS? But I was not aware of what was going on. I had no idea where the camera was, what lenses were used. I didn’t understand that at all. And then with Y tu mamá también it was the first time that Alfonso engaged us in the making of the film. We learned a lot. He used us as his accomplices—me and Diego — to work out the film. We became a family, like we were good friends. With Alfonso, and with El Chivo Lubezki, they became people who really explained everything patiently. They would explain to us what was going on. They realized that we were the kinds of actors that it didn’t matter that we knew what was going on. Because sometimes it’s best that the actors don’t know. We learned a lot while making that movie.

On Making Political Films

“There are people who’d like to think of politics like a tennis match. Something that happens somewhere over there. But that’s not me.”

You know, this is something interesting to explain because sometimes up front, especially presenting these films in Europe or the United States people wonder, “Oh so the films are very political!” You start to wonder, you know, apart from the obvious answer (“Everything is political… all relationships are political”), […] well, we’re brought up in countries where politics are very much on the surface of everything you do. Growing up in Mexico there was a huge devaluation when I was very little. You know, one day the money you have is worth three times less. There was a huge earthquake in 1985. There was the PRI Party — there was no freedom of expression. Consequently, symptomatically there was the rise of the Zapatistas. And that woke the nation. It woke up America. It was like, wait, the Indigenous people are not being heard, not part of this conversation of where we’re going. And being 14 at the time of the Zapatista uprising well, I got completely got involved, like lots of people in my generation. It all became really political all of a sudden. There was a huge political fraud in 1988. So, the films are political? Yeah. It would be crazy if they weren’t! I mean, Amores Perros and Y tu mamá también are intrinsically political movies. They are! They have that edge. And that’s where it comes from. There are people who’d like to think of politics like a tennis match. Something that happens somewhere over there. But that’s not me.

On Collaborating With Pablo Larraín

We get along so well! With Alfonso Cuarón, with El Negro González, with Walter Salles, with Michel Gondry, with Pablo Larraín — there’s a sense of friendship and just complete synchronicity, in terms of what we’re looking for, in the filmic aspect. Let’s accept it, I know he’s young, but he’s one of the best filmmakers in the world right now. He’s incredible! To do No is one of the most difficult films there is to do. And Neruda is very complicated — who can pull that off? He engages in difficult subjects. He plays with cinema, with the format, with different tones of acting. We have a strong communication. I love him as a friend, as a brother, as a confidante, as an accomplice. I adore the way we engage in a creative conversation.

On Creating Socially Conscious Work

I was invited by Amnesty International to do a piece on the migrants from Central America going to the U.S. through Mexico. At the time it was seldom talked about, but it was something that was boiling and it needed attention. Thankfully I was invited to do that. I proposed to do these 4 short films with a group of friends: Los Invisibles (look them up they’re on YouTube). Each engage on a different subject on the journey and their perils. It was interesting to engage with that, because as Mexicans we always know about the migration of Mexico to the United States but we never know how the treatment of people who go through Mexico is. It was a very eye-opening perspective, realizing and talking to them and understanding their plight. It’s even worse than the ones from Mexico trying to get to United States. Because those are countries some of them cannot go back to.

On Pursuing Stories About Immigrants

I’m interested in that because I’m a migrant. I’ve been migrating all my life. I can bet that all of you come from migrants. So it is a natural process of humanity — humanity is still alive thanks to migration. It’s a natural phenomenon and even if we downsize it to just economic terms, it’s something that had to happen. Even Adam Smith talks about this for fuck’s sake! For there to be free trade there needs to be free movement of labor. It’s sickening the way politicians play with that. And the way that politicians argue and lie about that and use migration as the main card to be dealt and to be like “Well, I’m gonna be against it because it appeases my electorate — the fear that they have of the Other.” It is ultimately what drove me to understand this journey. I feel such empathy because, again, I’m a migrant. And I will always.

On Fighting Anti-Immigrant Rhetoric

“I tell all of these kids, ‘Come to Mexico, we will receive you. And we need you. You will always have Mexico as a place where you’re welcome.’”

Oh man. How did we get here? It’s definitely heartbreaking. There’s one side of the argument we have no way of engaging with rationally. How do you convince someone who opens up his presidential career by saying that Mexican are rapists, drug traffickers, and bad people? Do we have to convince him that we’re not? How denigrating is that? That should be ignored if somebody says that. You can’t argue with someone who believes that. It’s impossible to engage with that. It’s very difficult. This ideology is a consequence of many years of developing this thought — up to a point where having free health care is a bad thing. It is an ideology that is constructed. It doesn’t come from nowhere. It’s done economically, with a lot of pressure, putting people in dire situations. That’s why there are no strikes. You’d think that with this president there’d be a lot of strikes — but because if they lose their jobs they lose their health care. We live in a moment when we have to highlight that this is a constructed ideology. It has nothing to do with any rational explanation. It is purely ideological. It is a lie. And this president is lying every single day. And he’s getting away with it all the time. I don’t know how the hell there are journalists who still have the stamina to write his name!

On What He’d Say to DREAMers

It is horrible. The world, but specifically the U.S. it’s really in a huge crisis. I don’t know how they’re gonna work it out. And now the consequence is that these kids, as you know the ones that receive this DACA program — they are the ones who are doing the right thing, who are going to school, they are scared to run a red light. Because if they do they’d get deported. They are the best citizens! The most law-abiding, quiet, doing their thing. They’re the ones being deported. Recently there were these two girls protesting and they said that they’re not going to be afraid, we’re gonna face this. And really, all of these kids should be doing that. And society and civil organizations should be joining them in doing massive strikes. To stop this lie from evolving. That’s what can be done in the United States. I’m Mexican, and I consider myself a Latin American — I don’t live in the United States, I have no desire to live in the United States — the only thing that we can do, that we have a responsibility to do [is] to tell all these kids from Mexico, from El Salvador, from Nicaragua, from Guatemala, from Colombia, that Latin America is also their home. And that they are welcome. Mexico is the mother they never knew, and the United States is the father that doesn’t want to recognize them. And they have to get to know their mother. Please, whatever I can do as a Mexican. I tell all of these kids, “Come to Mexico, we will receive you. And we need you. We need you because you were the guys that were left…”

Your parents were caught in a situation, economically, politically. And they went to the United States thinking of something. That their future was going to be brighter. This was your parents’ choice. Now you have also the choice to come back to Mexico if you want. And you will always have Mexico. If you want to stay in the United States, still, you will always have Mexico. You will always have Mexico as a place where you’re welcome.